Due to scheduled maintenance, the National Library’s online services will be unavailable between 8pm on Saturday 7 December and 11am on Sunday 8 December (AEDT). Find out more.

These activities are designed to activate students’ prior knowledge, develop critical thinking skills and establish an understanding of the key terms and concepts relating to World War I. They will help set the scene for the role media played in communicating news from the frontline to the home front. The activities will also help students to explore the concept of newsmaps. A variety of primary sources have been selected to show students the diversity of news material available at the time, and to support the development of interpretation skills.

Start by discussing with students the differences between media today and in 1914. Analyse some of the advances in communication and technology that have made access to information easier, or more challenging.

Key terminology:

- official war correspondent

- newsmap

- propaganda

- Australian Imperial Force (AIF)

- Allies

- monarchy

Background questions:

- Why did Australia declare war on Germany in 1914?

- What kind of media coverage of the war was there in 1914?

- What are some of the implications of a war only presented in print?

On the home front, people only had access to print media. What challenges would this have presented to them

What forms does media coverage take today, not just for conflicts in the world but for other topics as well, such as political events, entertainment and sports.

Fact or Fiction? The role of print media in World War I

What role did the media and official war correspondents have in World War I?

The invention of portable devices has changed the way in which we access news and information, making it almost instantaneous. At our fingertips, we can scroll between the internet, multiple social media platforms, YouTube and even television programs to see what is happening around the globe. This stream of information has resulted in the establishment of an endless 24-hour news cycle, compounded by multiple sources on any given topic, and often varying versions of events.

Gone are the days when only journalists reported on news; now there are bloggers, vloggers and insta-celebrities sharing their thoughts. The internet has also made the daily news cycle interactive with viewers able to comment and give their opinion on an issue. All of these advancements in news coverage has significantly affected the way we access, interpret and respond to global issues.

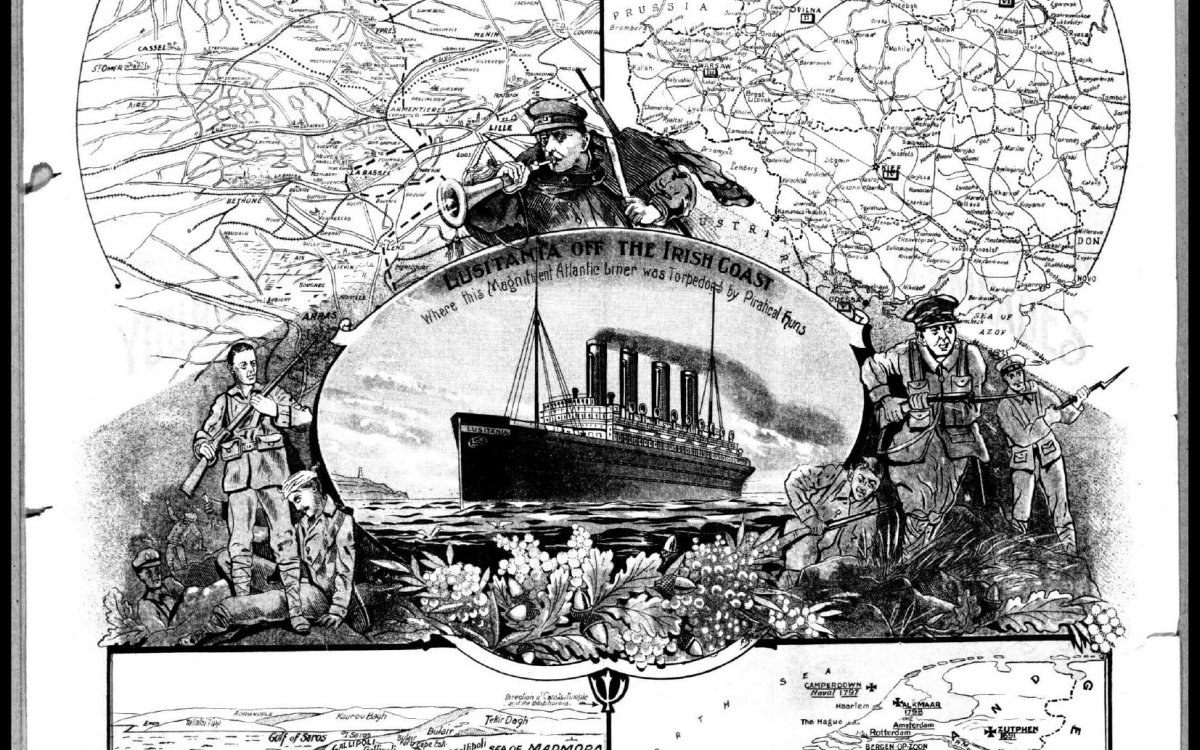

Take a step back in time to the beginning of World War I when newsprint was the main method of communication available to the public. Up-to-date news from the frontline came from journalists like Charles E.W Bean, Australia’s Official War Correspondent, and Ellis Ashmead-Bartlett, the British equivalent. Although many photographs were taken throughout the war, getting them to the Australian readership was a much greater challenge. Newspapers therefore relied on other means to inform their readers about what was happening on the other side of the world. Soon newspapers were printing cartoons, drawings and newsmaps, around which articles were constructed.

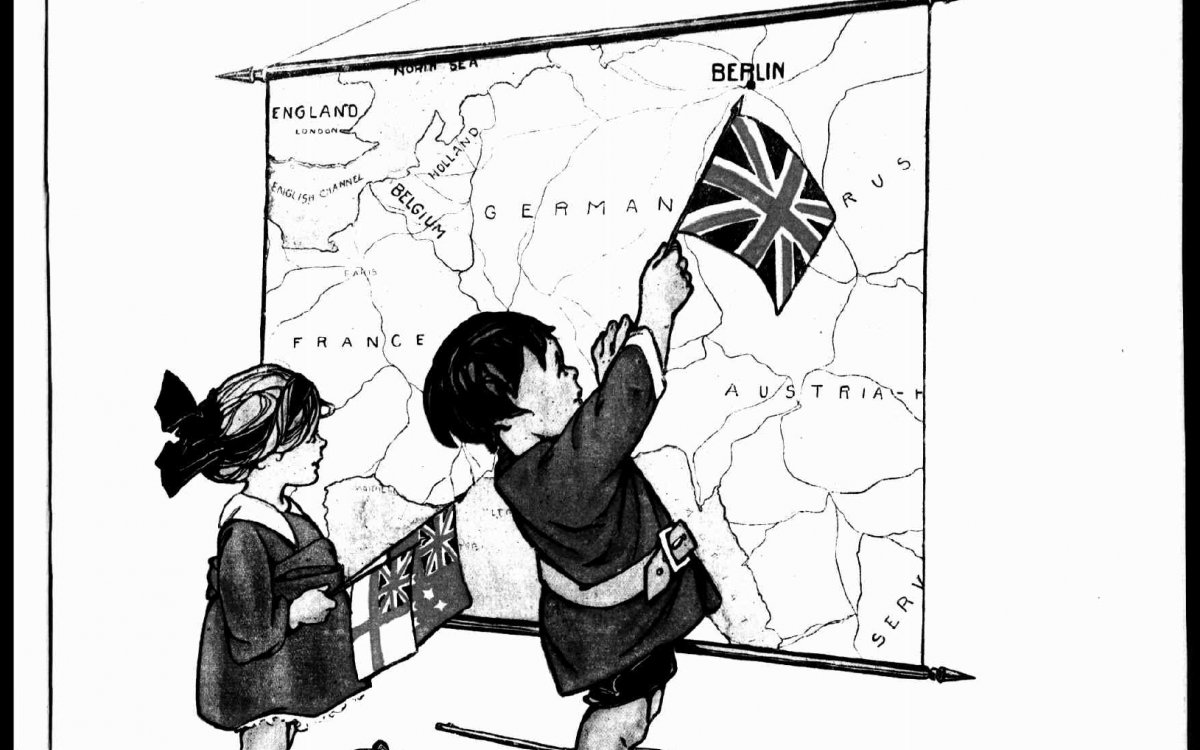

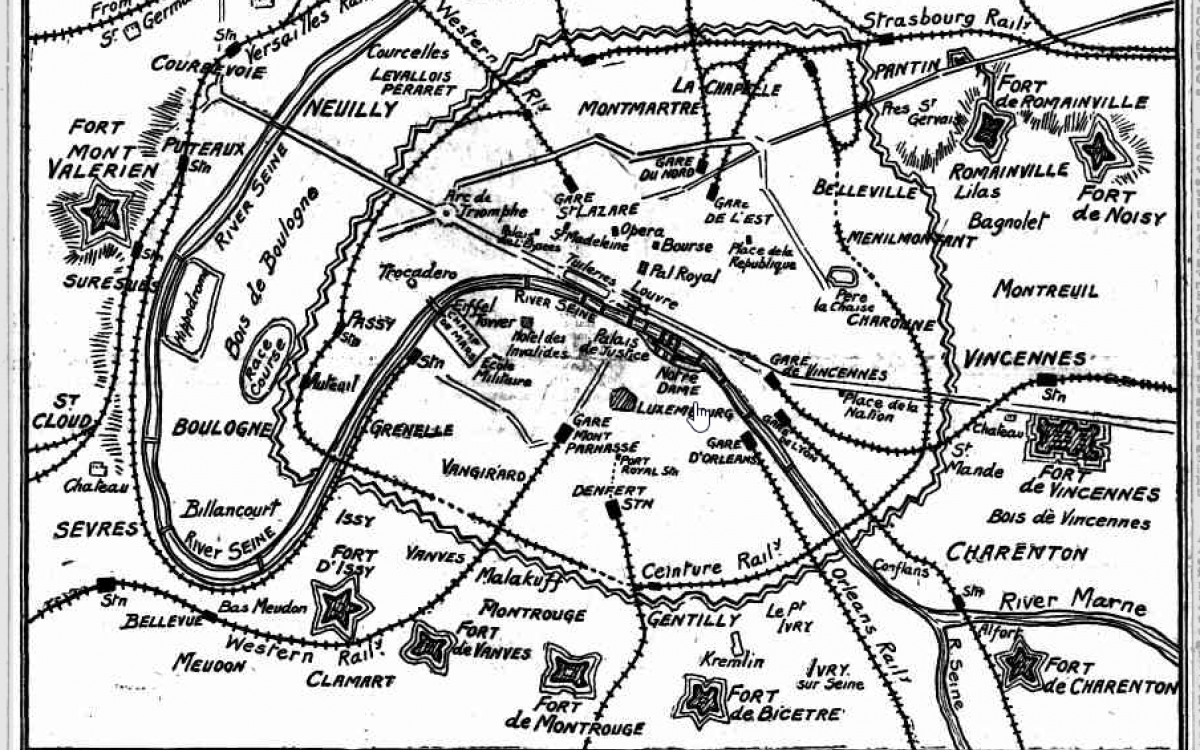

The newsmap became a window through which most news was viewed and understood. Daily maps introduced readers to the theatre of war, marking its progress. Day-by-day, for every campaign and battle, maps allowed readers across the nation to follow the exploits, successes and, sometimes, the disasters that befell the Australian Imperial Forces and the Allies. Suddenly, readers were introduced to places such as Palestine, Egypt, Belgium, Germany and France, some of which they had never heard before. Because actual war conditions could not be made public until after the war, newspapers invested in creating both propaganda and winning narratives.

The invention of portable devices has changed the way in which we access news and information, making it almost instantaneous. At our fingertips, we can scroll between the internet, multiple social media platforms, YouTube and even television programs to see what is happening around the globe. This stream of information has resulted in the establishment of an endless 24-hour news cycle, compounded by multiple sources on any given topic, and often varying versions of events.

Gone are the days when only journalists reported on news; now there are bloggers, vloggers and insta-celebrities sharing their thoughts. The internet has also made the daily news cycle interactive with viewers able to comment and give their opinion on an issue. All of these advancements in news coverage has significantly affected the way we access, interpret and respond to global issues.

Take a step back in time to the beginning of World War I when newsprint was the main method of communication available to the public. Up-to-date news from the frontline came from journalists like Charles E.W Bean, Australia’s Official War Correspondent, and Ellis Ashmead-Bartlett, the British equivalent. Although many photographs were taken throughout the war, getting them to the Australian readership was a much greater challenge. Newspapers therefore relied on other means to inform their readers about what was happening on the other side of the world. Soon newspapers were printing cartoons, drawings and newsmaps, around which articles were constructed.

The newsmap became a window through which most news was viewed and understood. Daily maps introduced readers to the theatre of war, marking its progress. Day-by-day, for every campaign and battle, maps allowed readers across the nation to follow the exploits, successes and, sometimes, the disasters that befell the Australian Imperial Forces and the Allies. Suddenly, readers were introduced to places such as Palestine, Egypt, Belgium, Germany and France, some of which they had never heard before. Because actual war conditions could not be made public until after the war, newspapers invested in creating both propaganda and winning narratives.

As a whole class, critically analyse the resources below. This material provides a cross-section of print media from the time. They show the need to critically evaluate information that was presented to the Australian public during the war.

Have the class answer these questions for each resource.

Who published the source? Why is this information important?

- What information can we gain from the source?

- How would the public have felt viewing the source?

- Is the source primary or secondary?

- What is the main purpose of the source?

Resources

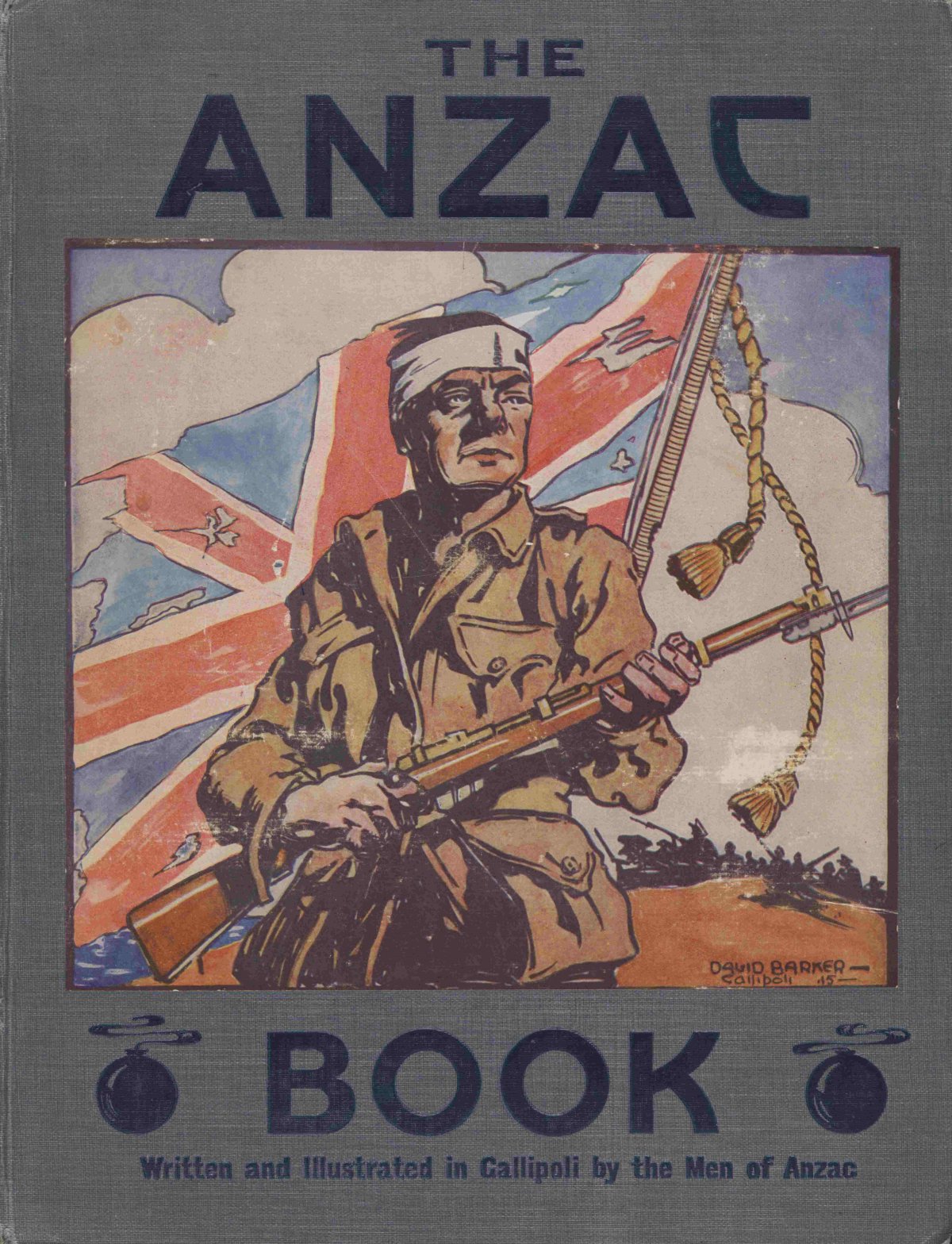

The Anzac Book

Australia. Army. Australian Imperial Force (1914-1921). (1916). The Anzac book / written and illustrated in Gallipolli by the men of Anzac. London ; New York ; Toronto ; Melbourne : Cassell https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-18456506

The Anzac Book was first published in 1916 and contained a collection of stories, poetry, cartoons, photographs and drawings from those who served on the frontline at Gallipoli. Edited by Australia’s official war correspondent Charles E.W. Bean, the book helped cement the Anzac ideology in readers’ minds. The collection highlighted the daily struggles faced by troops on the frontline, presenting a light-hearted insight into life in the trenches.

The Anzac Book was first published in 1916 and contained a collection of stories, poetry, cartoons, photographs and drawings from those who served on the frontline at Gallipoli. Edited by Australia’s official war correspondent Charles E.W. Bean, the book helped cement the Anzac ideology in readers’ minds. The collection highlighted the daily struggles faced by troops on the frontline, presenting a light-hearted insight into life in the trenches.

Full text of The Anzac book: written and illustrated in Gallipoli by the men of Anzac, Australian Imperial Force, 1916

- 'A present from home' page 64

- 'An ANZAC alphabet' pages 115-118

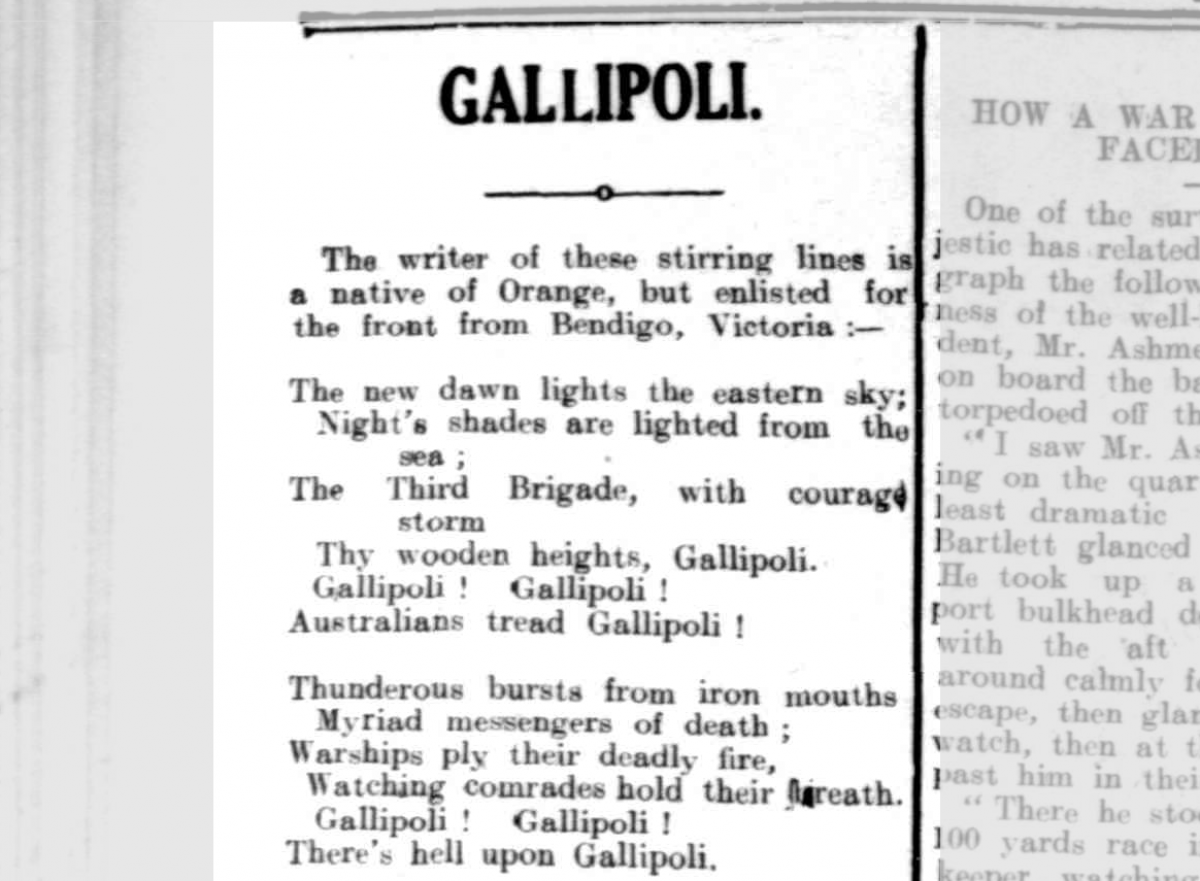

Gallipoli, poem by Sergeant Sydney Bolitho

GALLIPOLI. (1915, August 17). The Horsham Times (Vic. : 1882 - 1954), p. 2. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article73163746

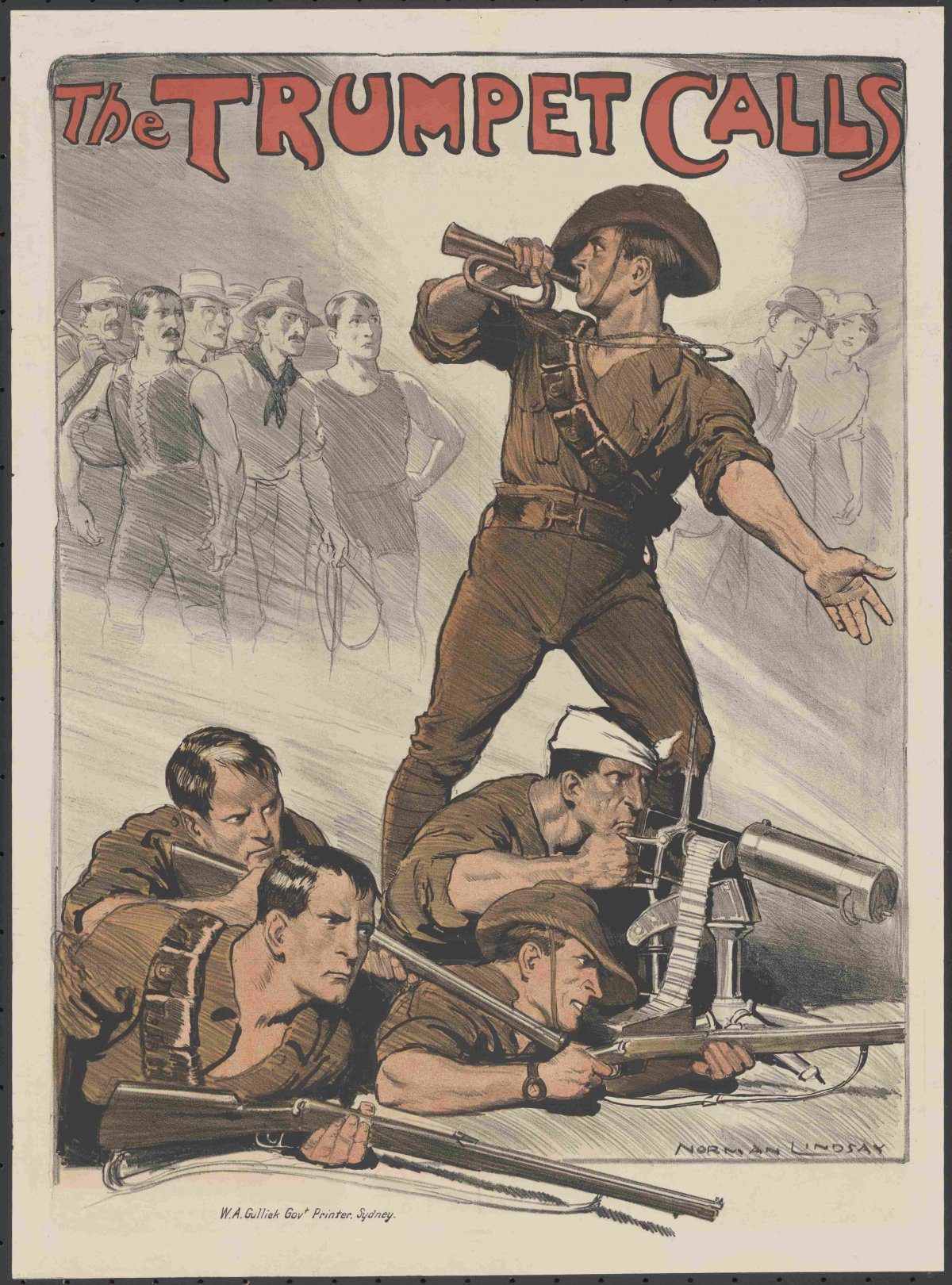

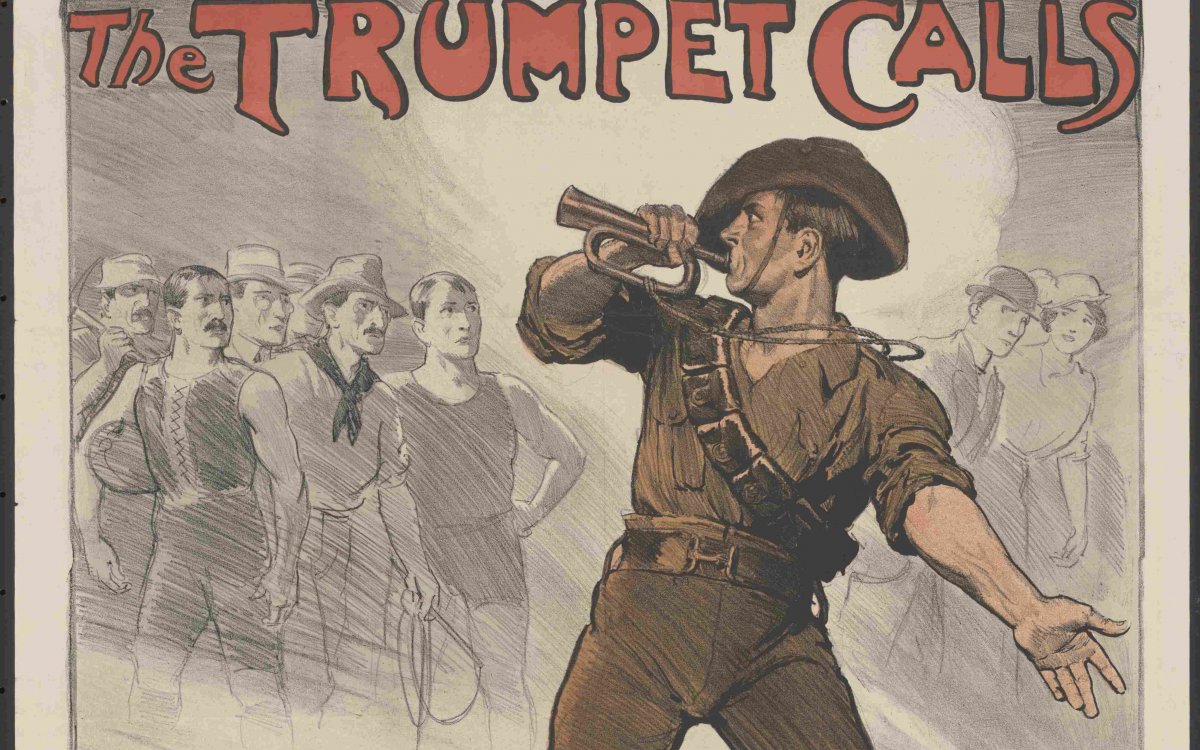

The Trumpet Calls Norman Lindsay

Lindsay, Norman, 1879-1969. (1918). The trumpet calls [picture] / Norman Lindsay. http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-136424612

The Trumpet Calls is a propaganda poster created by renowned Australian artist Norman Lindsay. The image shows a strong Australian soldier playing a trumpet (the call to arms) as he throws an accusatory look over his shoulder at a group of fit-looking civilian men in the background. In the foreground are four soldiers, also very fit-looking with determined faces, anticipating victory against the enemy.

The Trumpet Calls is a propaganda poster created by renowned Australian artist Norman Lindsay. The image shows a strong Australian soldier playing a trumpet (the call to arms) as he throws an accusatory look over his shoulder at a group of fit-looking civilian men in the background. In the foreground are four soldiers, also very fit-looking with determined faces, anticipating victory against the enemy.

‘Ashmead Bartlett’s Story of Dardanelles Overture’, The Sunday Times (Sydney), 13 June 1915, p.3

ASHMEAD BARTLETTS STORY OF DARDANELLES OVERTURE (1915, June 13). Sunday Times (Sydney, NSW : 1895 - 1930), p. 3 (ISSUED AS A SUPPLEMENT WITH THE "SUNDAY TIMES"). http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article120805647

The sources highlight the blurred line between fact and fiction that occurred during World War I, and the presentation of propaganda, which focused predominantly on the successes of campaigns and encouraged the recruitment of young men. This provides an interesting comparison between print media of the past and today’s journalism. It also highlights the need to scrutinise information carefully and critically analyse underlining messages.

What is in a newsmap?

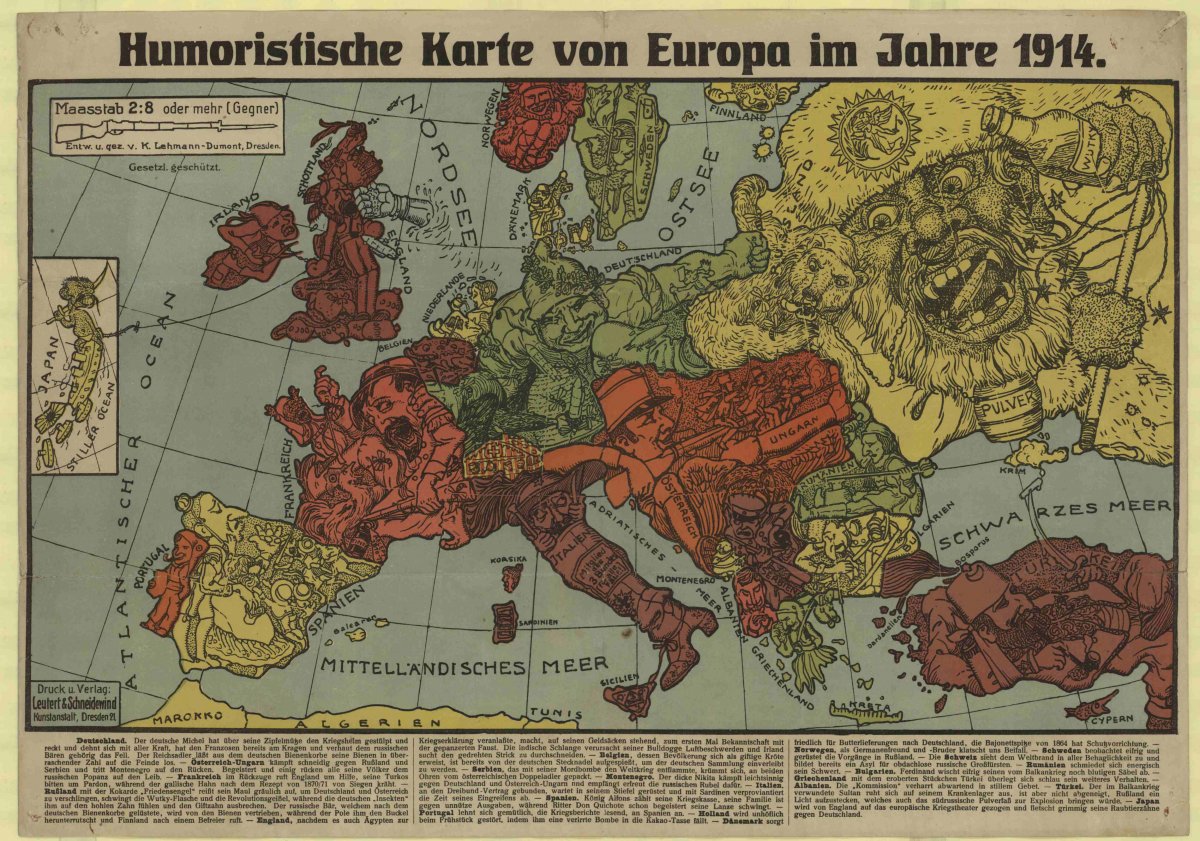

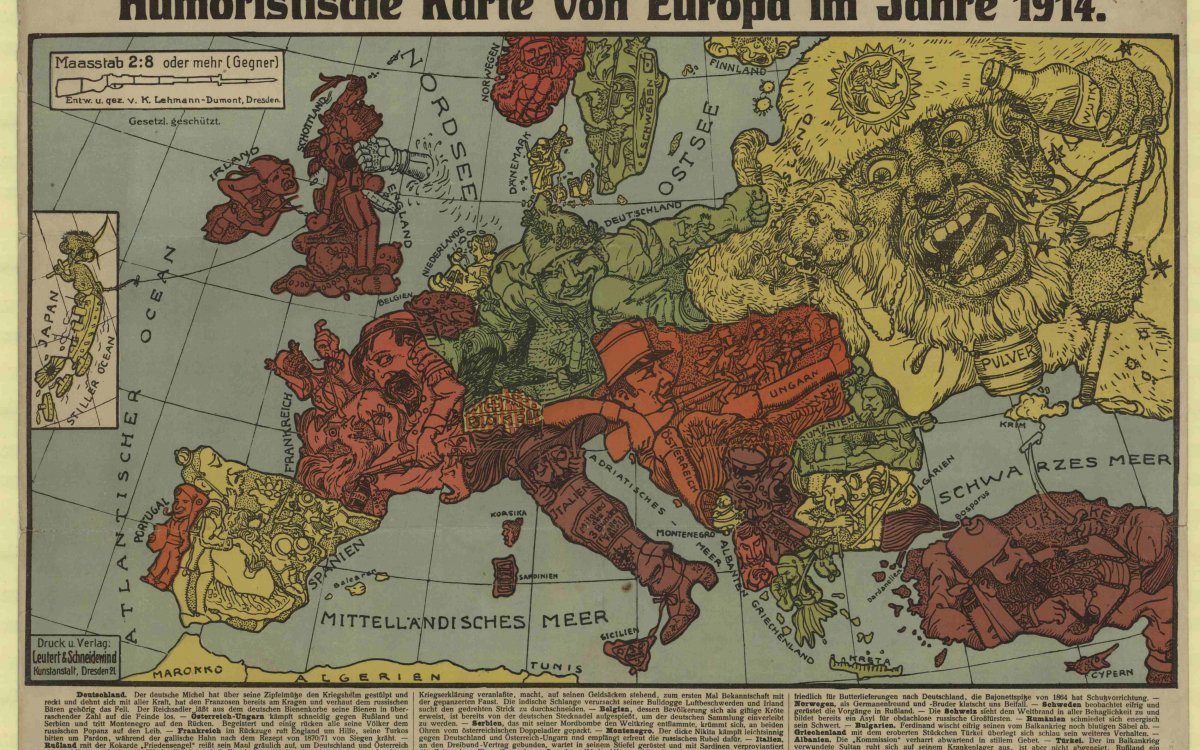

As a class, explore the newsmap by Karl Lehmann-Dumont, Humoristische karte von Europa im Jahre 1914 (Humorous Map of Europe in the Year 1914).

Lehmann-Dumont, Karl. (1914). Humoristische karte von Europa im Jahre 1914 / entw. u. gez. v. K. Lehmann-Dumont. http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-234418904

Humoristische karte von Europa im Jahre 1914 by Karl Lehmann-Dumont depicts the key players across Europe at the outbreak of the war. This caricature explores the war from a German perspective, focusing on the territorial wars between countries. Lehmann-Dumont is known for several wartime poster and card designs. In this example of the serio-comic map, the Deutsche Michel (the German Michael, who symbolises the German national character) has donned his war colours and already has the Frenchman by the throat, while punching the Russian Bear. Austria–Hungary fights cunningly against Russia and Serbia, while France in retreat calls to England for help. John Bull is shown standing on his moneybags, still coping with Indian and Irish problems. Belgium, in the form of a toad, has been pinned, to be added to the German collection. Turkey, wounded in the Balkan Wars, has recovered enough to light the south-Russian powder keg and Japan is dragged into the European theatre of war by her alliance with Britain.

Humoristische karte von Europa im Jahre 1914 by Karl Lehmann-Dumont depicts the key players across Europe at the outbreak of the war. This caricature explores the war from a German perspective, focusing on the territorial wars between countries. Lehmann-Dumont is known for several wartime poster and card designs. In this example of the serio-comic map, the Deutsche Michel (the German Michael, who symbolises the German national character) has donned his war colours and already has the Frenchman by the throat, while punching the Russian Bear. Austria–Hungary fights cunningly against Russia and Serbia, while France in retreat calls to England for help. John Bull is shown standing on his moneybags, still coping with Indian and Irish problems. Belgium, in the form of a toad, has been pinned, to be added to the German collection. Turkey, wounded in the Balkan Wars, has recovered enough to light the south-Russian powder keg and Japan is dragged into the European theatre of war by her alliance with Britain.

Have the students answer these questions:

- Each of the countries is represented by a caricature and a collection of unique symbols. What are the symbols and what do they represent? Why do you think the author created the map in this way?

- Why would maps like this have been appealing to the public?

- What country do you think the author is from? Why do you think this?

- Does knowing the author’s country of origin change your perception of the information presented?

- Think about print media today. Where would you find a similar use of caricatures as a commentary on events?

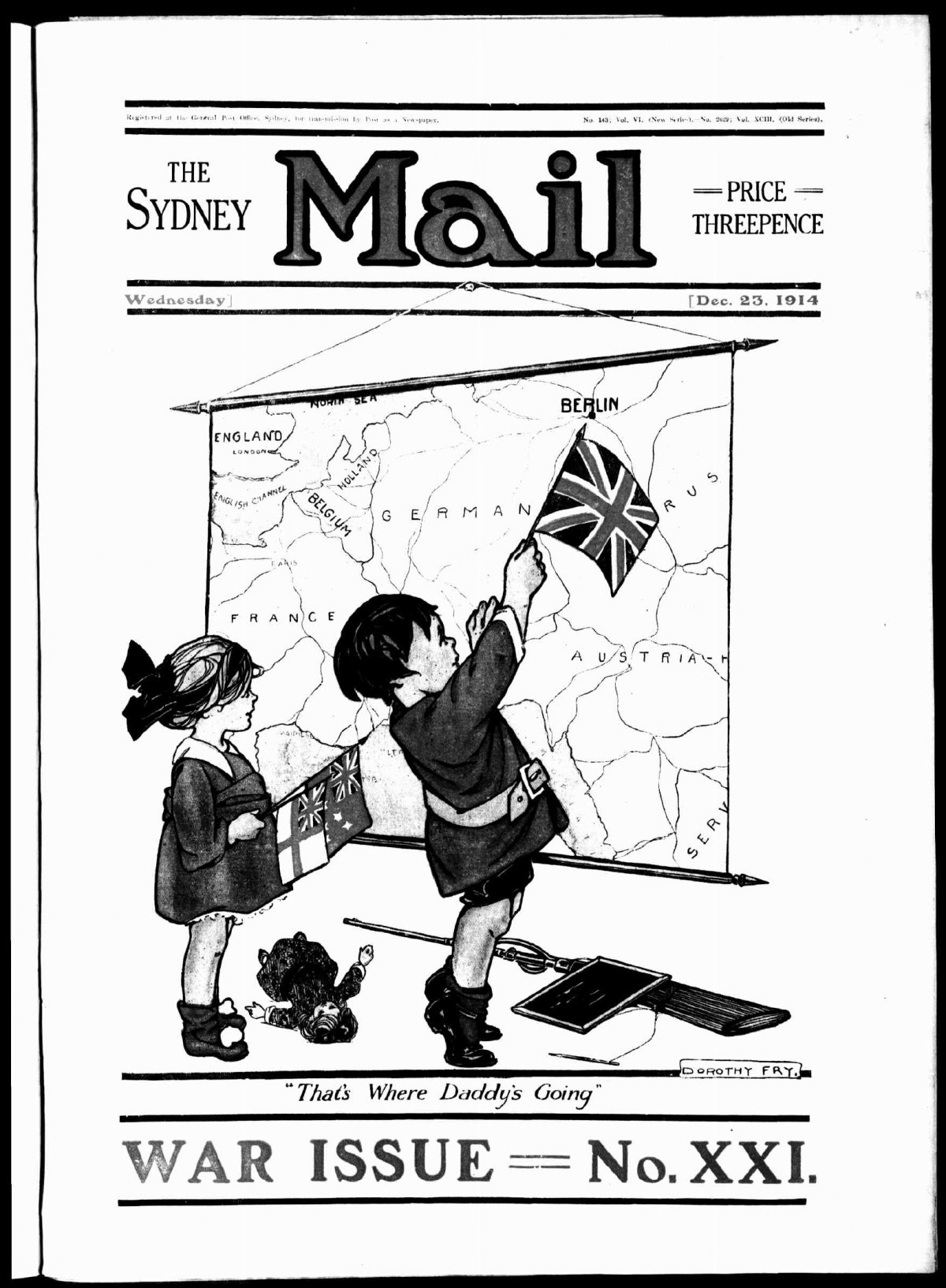

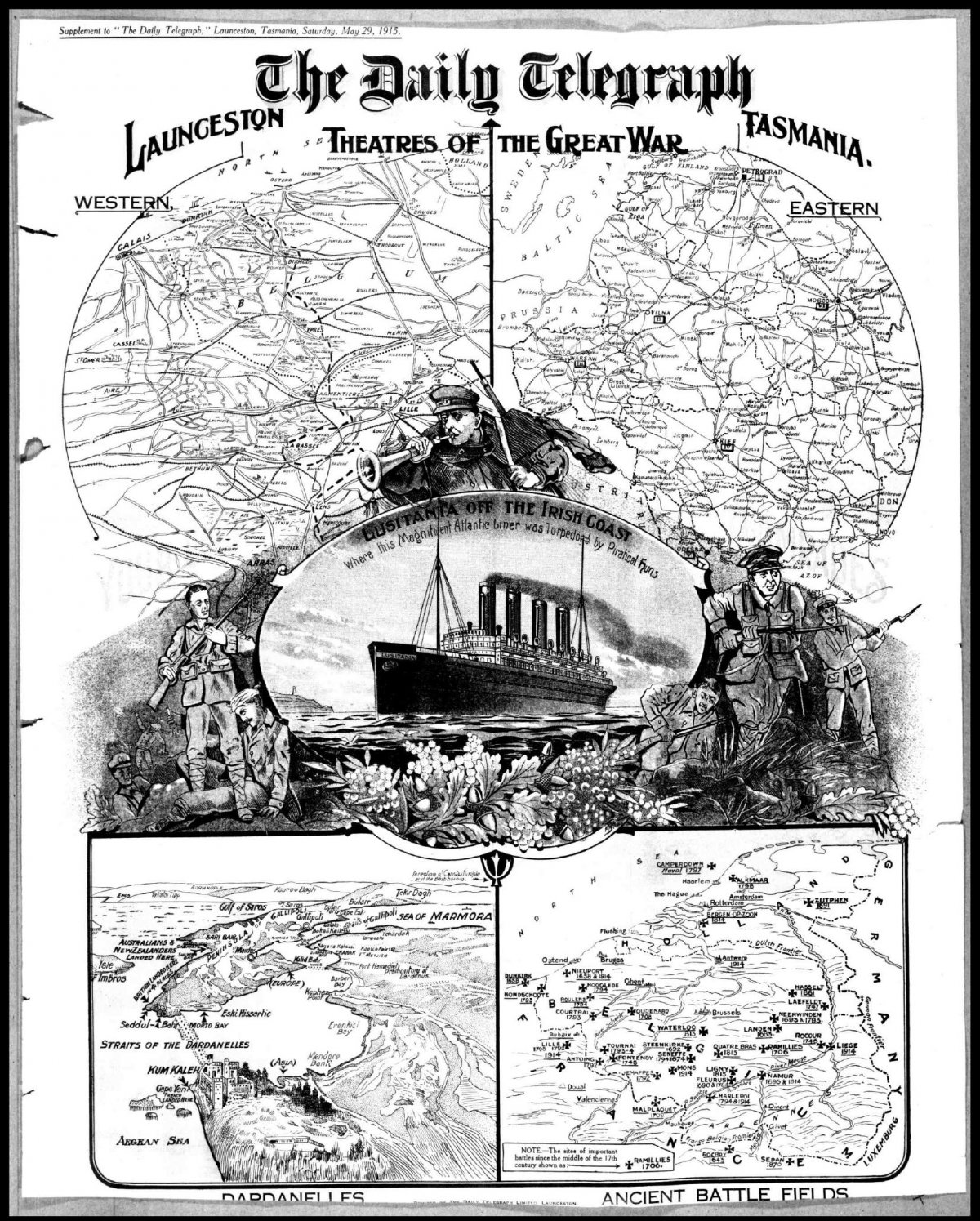

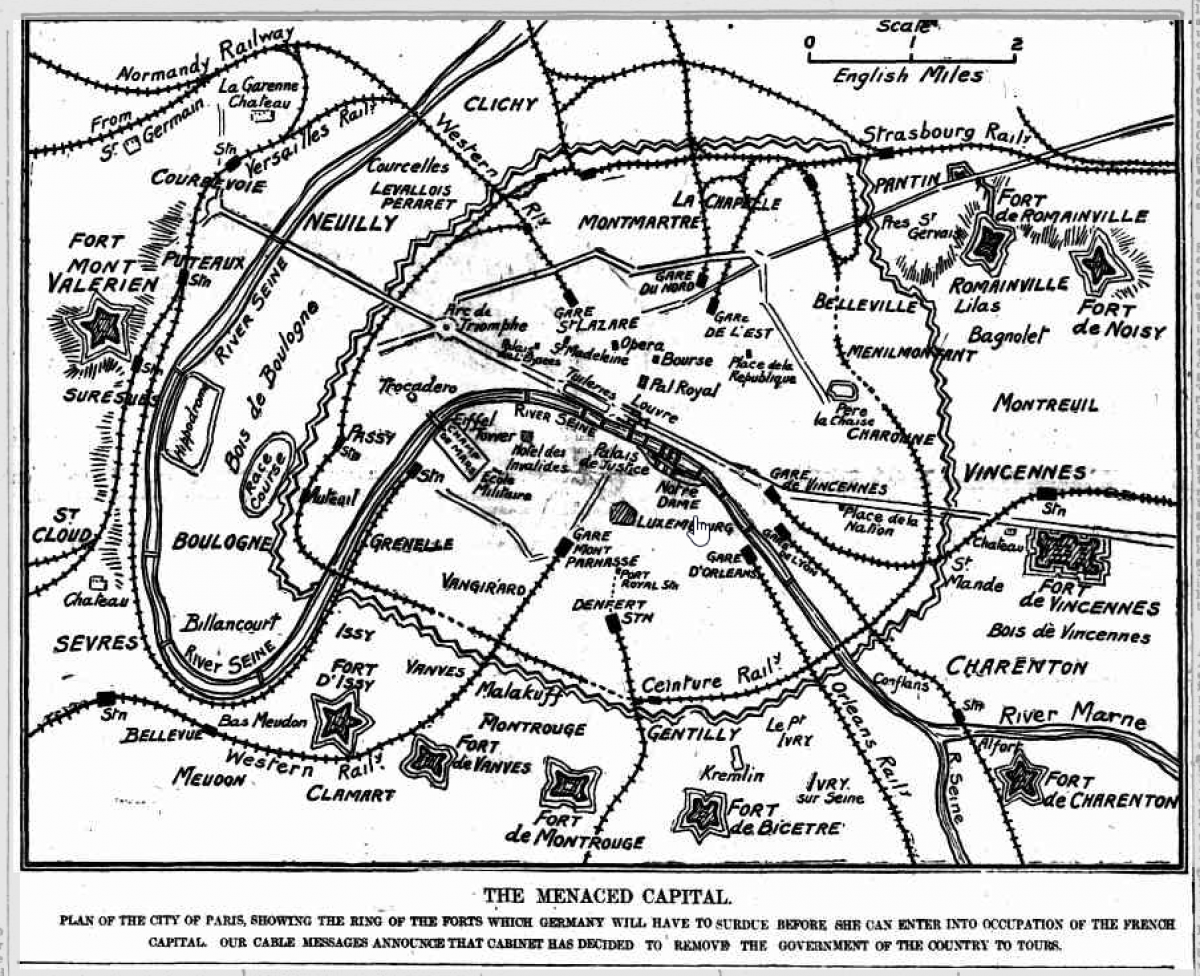

The following images are newmaps published in various Australian newspapers between 1914 and 1918.

Have students select a newsmap to investigate further. A selection is available below or students can explore Trove to find their own.

- The Sydney Mail 23 December 1914, p.1

- ‘Theatres of the Great War’, The Daily Telegraph (Launceston, Tas.), 29 May 1915, p.1

- ‘The Menaced Capital’, The Register (Adelaide), 4 September 1914, p.5

Use the following questions to support students’ interrogation of the newsmaps.

- Who published the newsmap?

- What symbols are presented in the map?

- What message is the newsmap trying to convey?