Uncover the life of Ellis Rowan

Artist and naturalist Marian Ellis Ryan was born in the Port Philip District (now Victoria) on 30 July 1848. She was the eldest child of Charles and Marian Ryan, and was always known by her middle name. Her maternal grandfather was natural history illustrator John Cotton, whose sketchbooks she inherited and are now part of the National Library’s collection.

Sir John Longstaff, Ellis Rowan Memorial Portrait, 1926, nla.cat-vn1901331

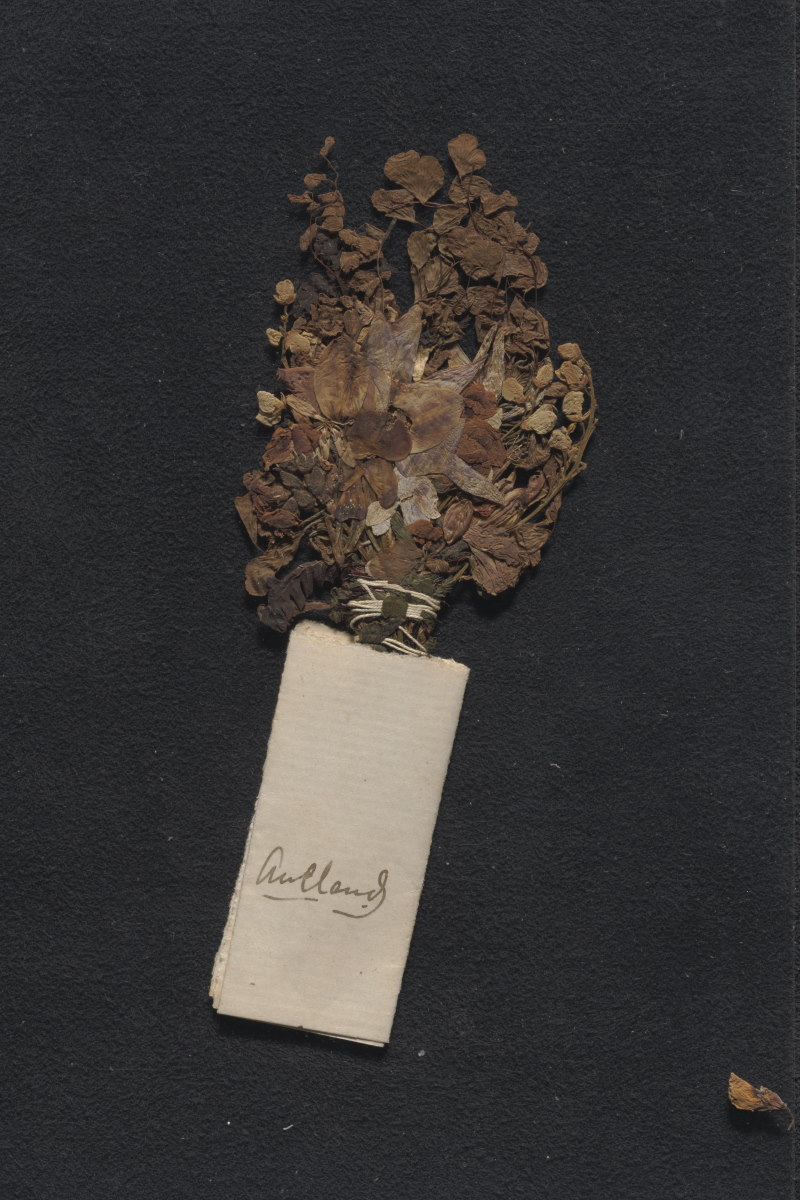

Art and nature were the driving forces in Rowan’s life. She did not formally study natural history, and it is not known how much art tuition she received. Rowan developed an individual style, and crafted paintings that celebrated the beauty of her subjects while also demonstrating sophisticated paintings skills. An early journal held by the Library includes sketches, notes and transcriptions of poems, as well as dried plants. It offers insight into Rowan as a young woman, revealing her interest in art, plants and writing. She first exhibited her work at the Intercolonial Exhibition in Melbourne in 1872, winning a bronze medal.

Ellis Rowan, a pressed bouquet of flowers from Ellis Rowan's Journal, 1859-c.1870, nla.cat-vn4365165

Her interests were supported by her family and her husband, Frederic Charles Rowan, whom she married in 1873. This support was significant, given the professional limitations Victorian-era women experienced. Her father’s purchase of land near Mount Macedon, Victoria, in 1872 is believed to have contributed to her passion for Australian wildflowers. Time spent living in New Zealand shortly after her marriage also contributed to her decision to paint professionally, as she did not take to domestic life, discussing this period decades later in 1912:

‘I was suddenly cut off from all social pleasures … and here, for the first time, I was thrown entirely on my own resources … here for the first time I commenced … getting as good a collection of Australasian flora as I could.’

Although Rowan is best known for her paintings of Australian wildflowers, she also admired birds, and other life forms. This included butterflies and other insects, which often appear in her watercolour paintings. She preferred to work en plein air, which often involved hiking to remote areas where wildflowers grew, wearing the long, delicate dresses sported by fashionable women of the time. Gifted in composing images, Rowan’s work became bolder over the years as her confidence grew. Her paintings, as Patricia Fullerton has observed, also show an awareness of pattern and decorative expression—something promoted by the popular Aesthetic Movement which celebrated the notion of ‘art for art’s sake’.

Ellis Rowan, Erythrina variegata L. synonym Erthrina indica Lam., pale flowered form, family Fabaceae, Queensland, 1891?, nla.cat-vn1317791

Rowan’s fascination with the natural world, together with her talent and determination, led her to become a highly decorated artist. Early on in her career, her talents were recognised by Victorian government botanist Ferdinand von Mueller, an acquaintance of her father’s who was appointed director of Melbourne’s Royal Botanical Gardens. Von Mueller engaged Rowan to assist him in documenting Australian plants, and she located and identified many species for him. Rowan was one of several women artists who von Mueller engaged in this way, bucking the trend that saw natural history as a male-dominated pursuit. Although she assisted von Mueller, her clear sense of self and own artistic objectives never wavered; she resisted his suggestion that she study botanical art in Germany, instead pursuing her own course.

Ellis Rowan, A Flower Hunter in Queensland and New Zealand, 1898, nla.cat-vn2519801

Rowan thrived on ‘hunting’ flowers and painting them, as can be seen by the size and breadth of her artistic output. She exhibited internationally, winning many awards and admirers, and also enjoyed writing about her work and her travels. This can be seen in her popular book A Flower-hunter in Queensland and New Zealand (1898). Here she wrote about her artistic motivation:

‘The excitement of seeing and the delight of finding rare or even unknown specimens abundantly compensated me for all the difficulties, fatigue, and hardships’.

Rowan enjoyed professional success during her lifetime. One of her many achievements was being awarded the First Order of Merit and a gold medal for her entries at Melbourne’s Centennial International Exhibition in 1888. Other entrants including celebrated painter Tom Roberts. Her success ruffled feathers in the art world, which led to a letter of protest from the Victorian Artists’ Society. At the time, so called ‘flower paintings’ executed in watercolour were not seen to be on the same level as narrative oil paintings. Rowan's gender may have also been a factor in the outrage. In total she won 29 medals through exhibitions nationally and internationally.

Further success came when Rowan’s works entered the Royal Collection of Queen Victoria. In 1895, Rowan paid a visit to Princess Beatrice in London and was surprised to be joined by her mother, Queen Victoria. She gifted the Queen three of her artworks, which remain part of the Royal Collection. In 1920, she held what was, at the time, the largest solo exhibition in Australia at Anthony Horden’s Gallery in Sydney, and made a sales record for a woman artist. A significant part of her collection was also acquired by the Queensland Government and is held at the Queensland Museum.

London War Office, British & German New Guinea, 1906, nla.cat-vn7374235

Rowan constantly travelled, often independently, in search of wildflowers and other natural delights. Her first overseas trip in 1869, when she was aged just 21, took her to London, where she may have taken art lessons. Her independence and sense of adventure took her throughout Australia—including on visits to Western Australia, Queensland and the Torres Strait Islands—and overseas to places including North America. On her many trips in Australia and overseas she stayed with friends and made new ones. These contacts providing essential support to enable her to fulfil her artistic goals. Her visits to New Guinea in 1916 and 1917 came at a time when it was uncommon for women of European descent to travel to the region independently. There, she befriended Irish travel writer Beatrice Grimshaw, who hosted Rowan on her visit to the island of Sariba and provided her with advice on the region. These trips to New Guinea were to be her final adventures, as she contracted malaria. She returned to Australia in late 1917, her health weakened, and she never fully recovered.

Explore the work of Ellis Rowan with the National Library:

- View the Birds of Paradise paintings

- View the Birds of Paradise plate designs

- Dive into the Library's Ellis Rowan Collection

- The flower hunter in New Guinea Blog by Dr Grace Blakeley-Carroll

- View the digitised collection

Return to the exhibition homepage