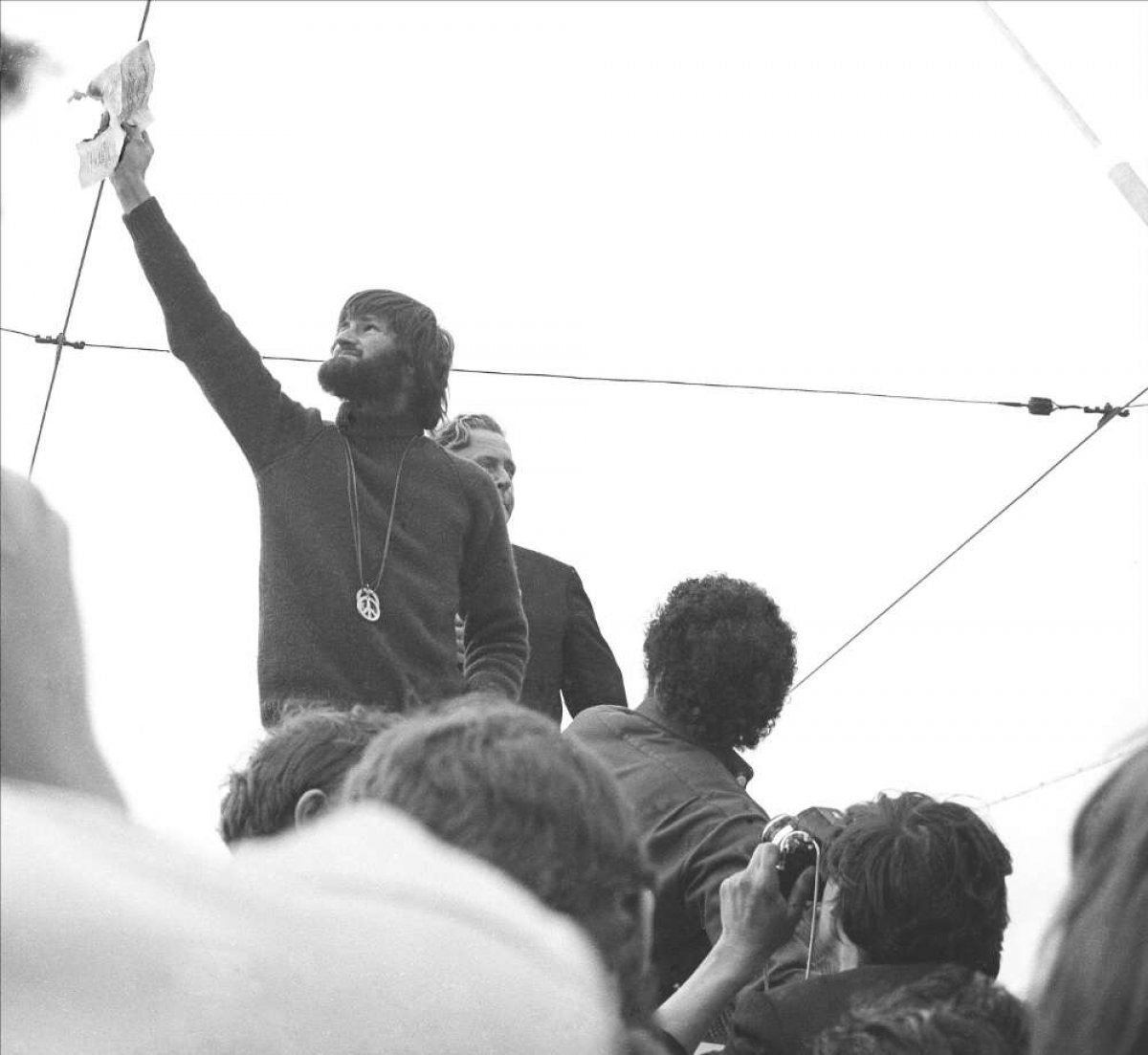

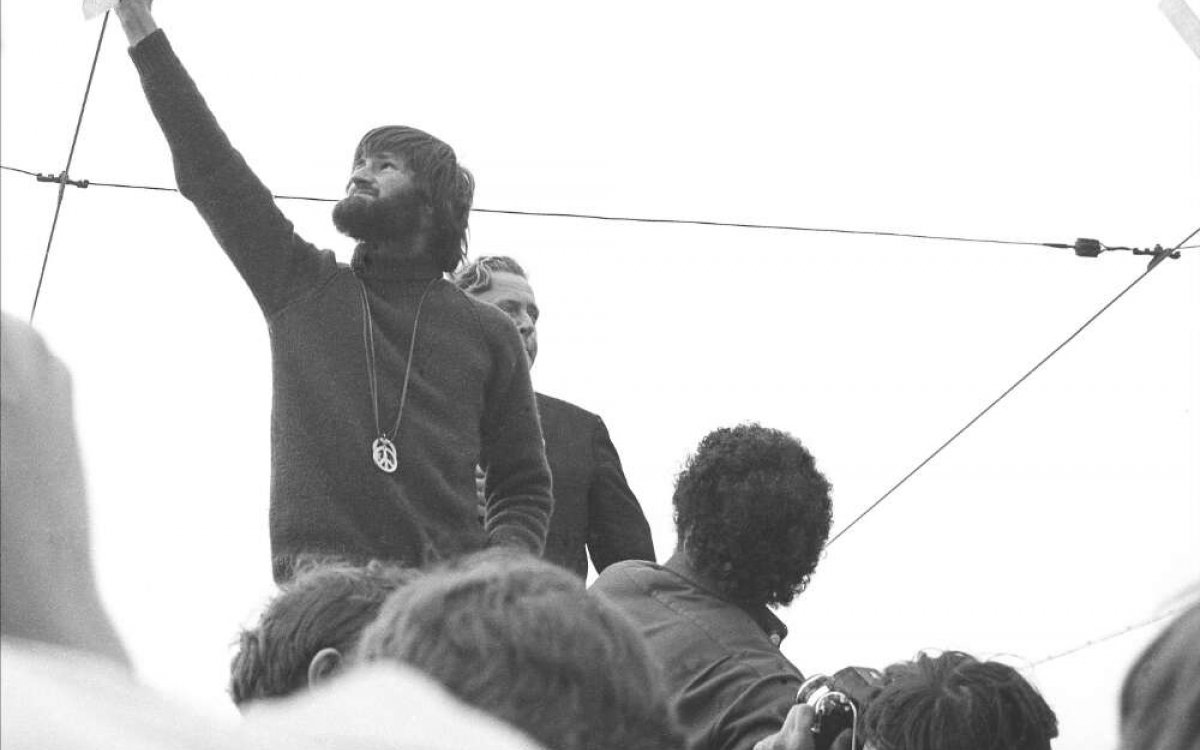

Aickin, Tim. (2010). A protester burns his draft card, standing in front of Jim Cairns, Vietnam War Moratorium Day, Melbourne, May 1970 [picture] / Tim Aickin. http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-138060747

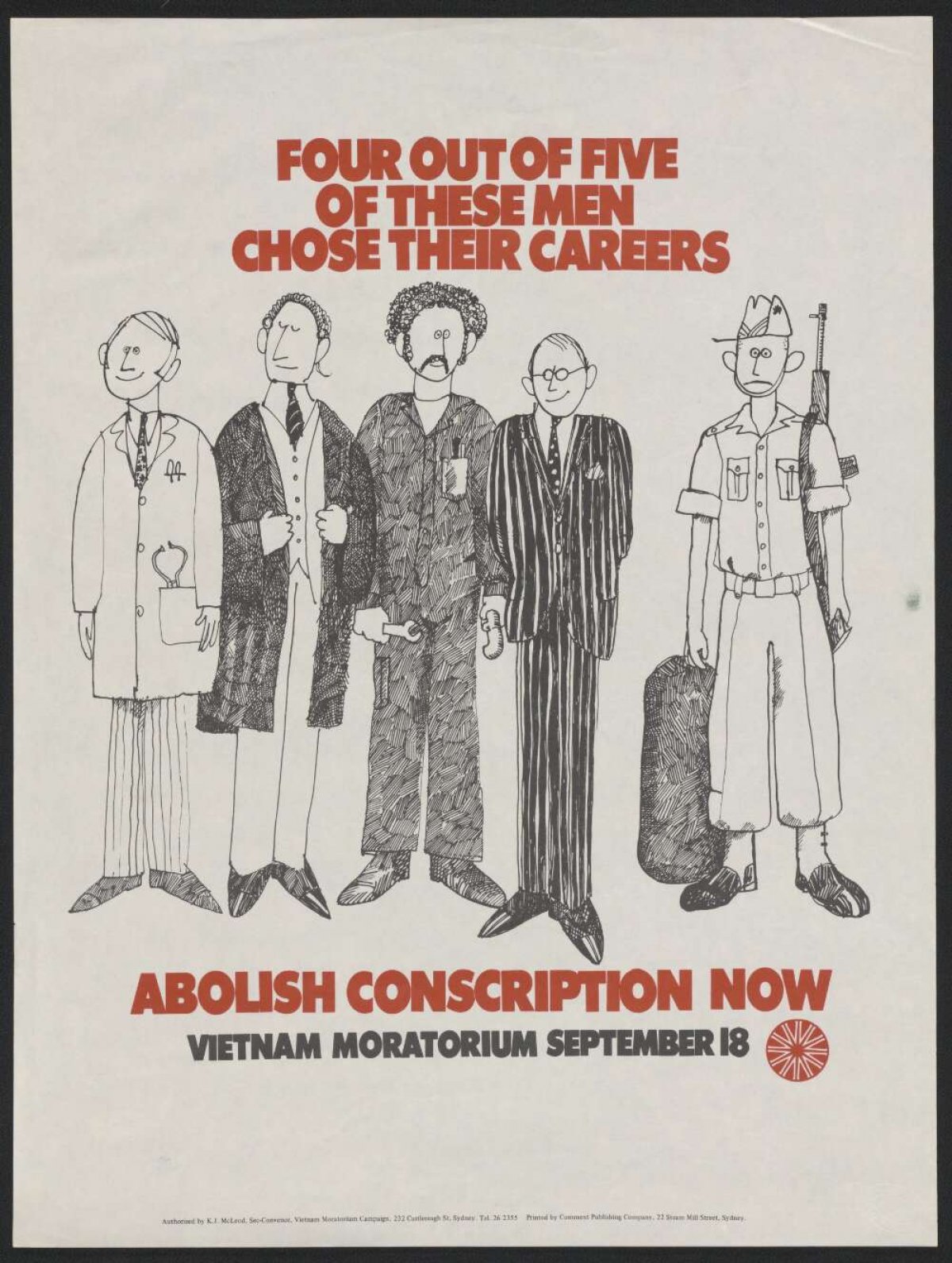

Comment Publishing Company & Murray Sime & Vietnam Moratorium Campaign (Australia). (1967). [Collection of Australian anti-conscription posters in the Vietnam War] [picture]. https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-135759587

Reiss, Francis, 1927-2017 & Reiss, Francis, 1927-2017. (2003). Protesters gathered outside the State Library in Swanston Street, Melbourne peace rally, 14 February 2003 [picture] / Francis Reiss. http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-147324313

Direct action can be separated into two categories:

Civil Resistance

Civil resistance is a broad term used to describe the use of non-violence to bring to the forefront a troubling issue. Forms of this kind of action include:

- marches

- demonstrations

- boycotts

- silent vigils

- petitions

- peaceful street protest

- picketing.

Civil Disobedience

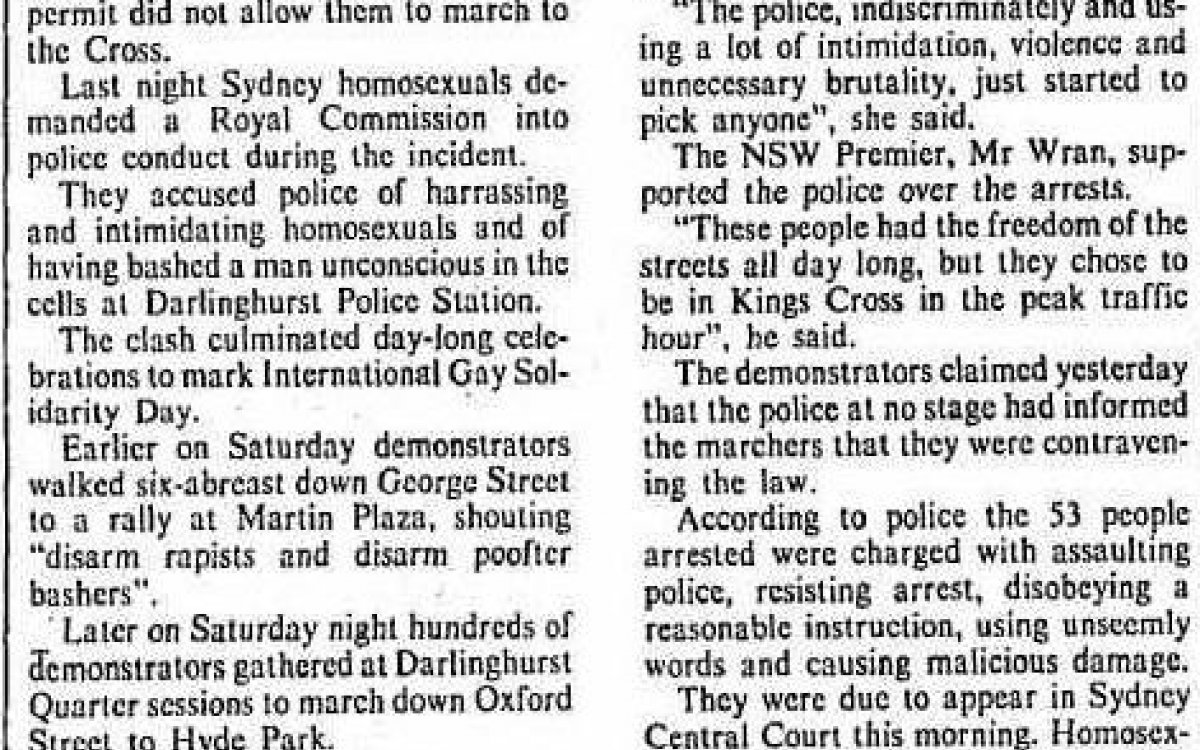

Civil disobedience is the use of non-violent means to raise an issue, but with the deliberate refusal to obey laws or protocols set by governments. The purpose for this type of protest form has been defined as to ‘trigger heated public debate’, however Executive Director of Change.org Sally Rugg cautions that protestors need to avoid being too divisive because they need to foster sympathy for their cause. The term civil also holds the implication of ‘non-violent’. This kind of action has included:

- draft dodging (burning draft cards)

- illegal leafleting

- street sit-ins

- breaking of protest permits

- mass mobilisation to break business-as-usual mentality.

Throughout Australia’s history, activist groups have used many of these protest forms as a way to catch the public’s attention and to express their opinions on current issues. Some protesters have chosen acts of civil resistance, others have chosen civil disobedience and some have chosen mixture of both methods.

Aboriginal Tent Embassy

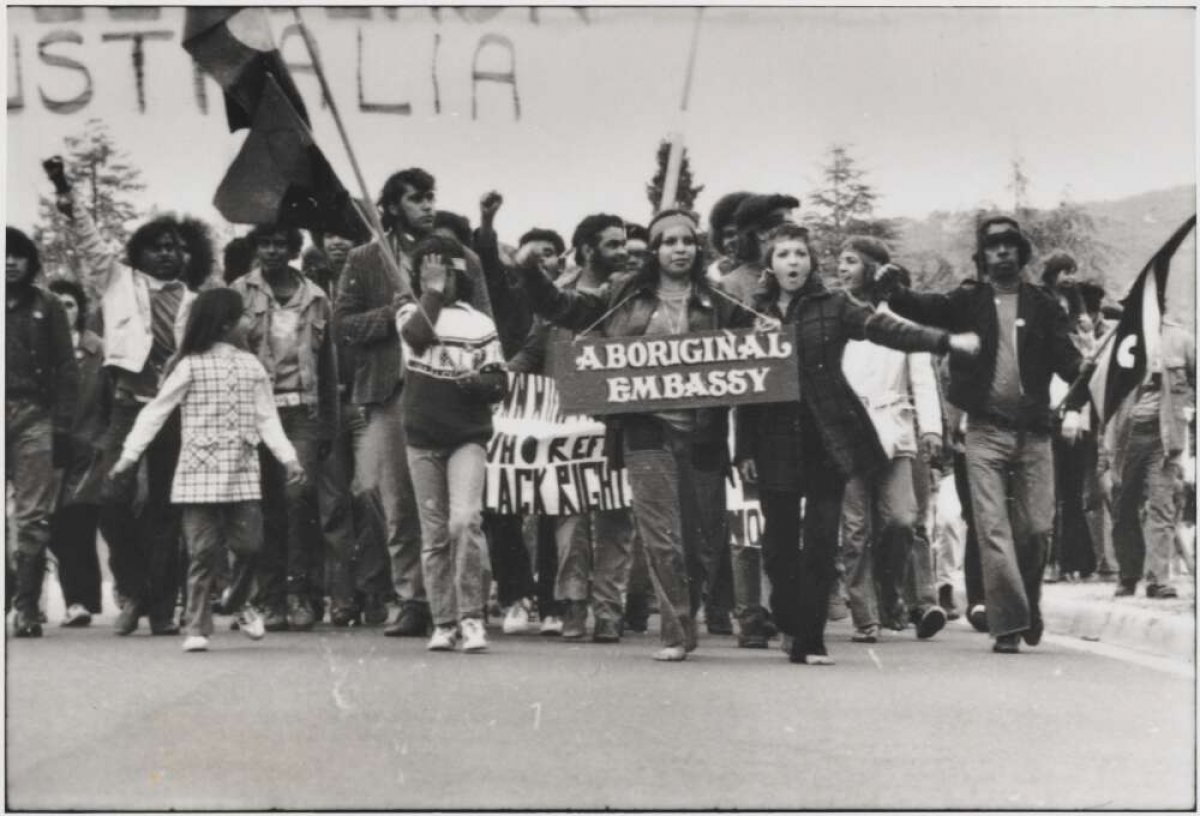

Middleton, Ken, (Kenneth Thomas) 1948-. (1972). [Demonstration with 'Aboriginal Embassy' placard at land rights demonstration, Parliament House, Canberra, 30 July 1972] [picture] / Ken Middleton. http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-149418064

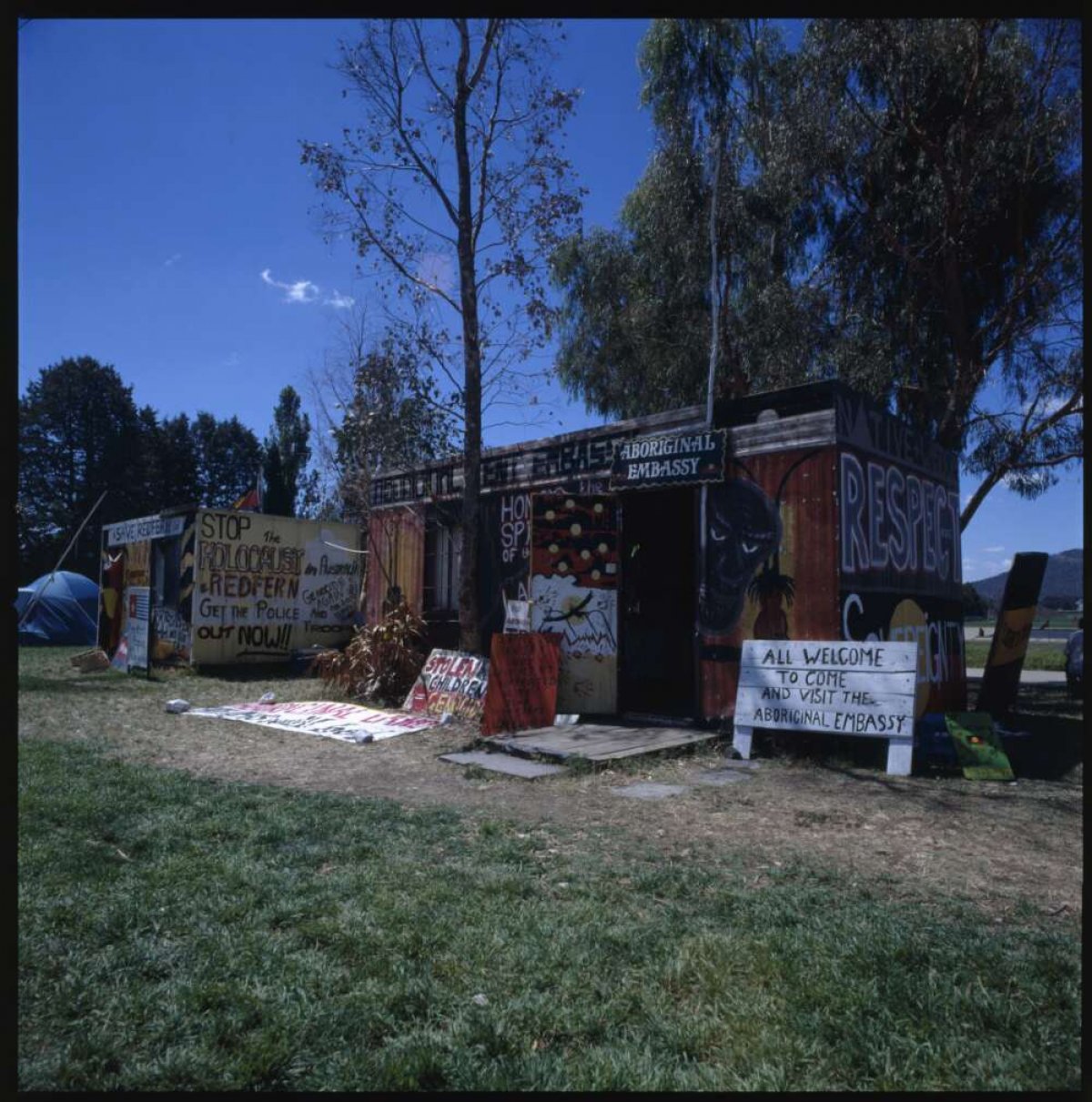

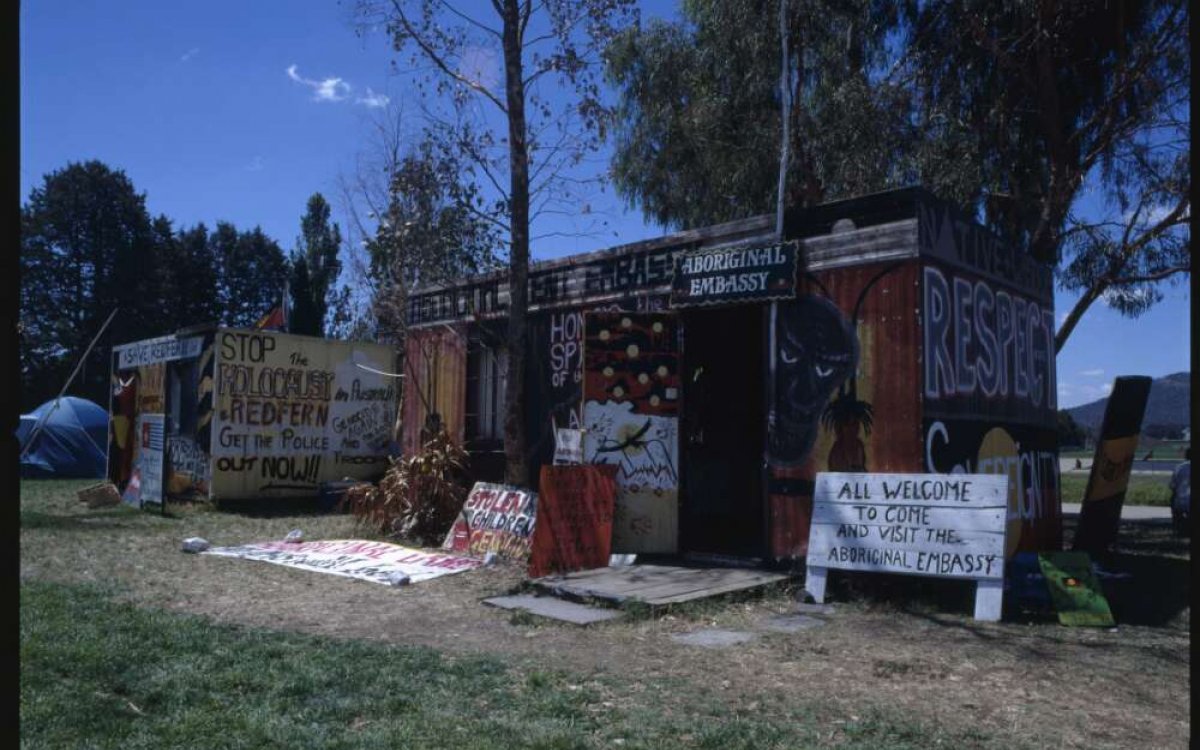

Seselja, Loui, 1948-. (2002). [The Aboriginal Tent Embassy on its 30th anniversary, Canberra, 26 January 2002] [transparency] / Loui Seselja. http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-149952728

The establishment of the Aboriginal Tent Embassy in 1972 resulted from the Australian Parliament’s reluctance to grant First Australians rights to land, or protections of their cultures. In a statement on Australia Day (now referred to by many as Invasion Day) that year, then-prime minister William McMahon said that instead of land rights, First Australians would be offered lease arrangements. These arrangements didn’t recognise First Australians’ connections with, or traditional ownership of, the land.

This announcement caused outrage in First Nations communities, especially in the Sydney suburb of Redfern. Young activists in the Redfern area, including Black Power group Black Caucus, held meetings to decide what action could be taken. Community sentiment was that parliament was out of touch with issues faced by First Nations groups in terms of health, poverty, unemployment and, most importantly, the growing desire for land rights. These meetings ultimately decided that direct action should be taken immediately in Canberra.

Four Aboriginal men—Michael Anderson, Billy Craigie, Tony Coorey and Bert Williams—drove from Sydney to Canberra on 26 January to begin the protest. They settled on the lawns of Parliament House (now Old Parliament House) in the early hours of 27 January. They had a beach umbrella and materials for signs, on which slogans were written such as ‘Land rights now or else’ and ‘Land now not lease’, and they also had a sign identifying the camp as the Aboriginal Embassy. Soon after, police arrived to investigate, and it was then that a loophole in legislation was discovered that allowed protesters to camp on Parliament House lawns indefinitely. Throughout the life of the original Tent Embassy, confrontations with police occurred when protesters prevented attempts to take down the embassy.

The original Tent Embassy lasted for six months, until the government introduced new laws in July that banned camping and the erection of tents on the lawns of Parliament House. Police forcibly evicted Tent Embassy residents. The ACT Supreme Court later ruled against the use of those laws to prohibit the Tent Embassy.

For many First Australians, the original tent embassy movement symbolised the hope of obtaining land rights. Since then it has become a broader symbol of Aboriginal protest against government treatment of First Australians.

Activities

Divide the class in half and ask them to conduct a debate relating to direct action, with one half arguing for the affirmative and the other for the negative. Choose one of the following propositions to debate:

- peaceful protest is pointless

- breaking laws as a form of protest delays progress.