Rebecca Bateman: Yaama, everybody, and welcome. My name's Rebecca Bateman. I'm the Director of Indigenous Engagement here at the National Library of Australia. I'm a Weilwan and Gamilaroi woman and very proud to be here tonight to be part of this event. I would like to start off by handing over to Aunty Violet Sheridan to welcome us to country.

Violet Sheridan: Thank you, and what a pleasure it is to be here this evening for the launch of the Margaret Tucker book. I met Aunty Marg many, many, many, many moons ago when I was a young woman, and it was in Melbourne. And I lived at that time in Northgate with Sir Douglas Nichols and Lady Gladys. So in that time, the Advancement League was not far away from the hostel, so I was a casual reception foreman back in the day that McGinnis was there. It really, when you're a young woman and you meet certain people that make a big impact in your life, and Aunty Marg made that impact in my life. And I've seen her a couple of months ago on the ABC, and I looked at her and I will listen and I couldn't take my eyes off her because she was one of those people that you'd memorise. And I thought, what a beautiful, beautiful soul she was. She was soft spoken but to the point. She wouldn't take a backward step. So I am over the moon that I've been asked to come along at the launch and welcome you.

But before I go into my welcome, I'd like to acknowledge members of her family here tonight. And it is my pleasure to welcome you to my mother's country. My mother is a Ngunnawal woman. My father is a Wiradjuri man, but I follow my matriarch's bloodline. So it is my pleasure. I believe a welcome to country is a traditional Aboriginal blessing, symbolising the traditional owners of the land welcome you. But it all shows respect for the first peoples of the land you are meeting on. I suppose it's a little bit about not going to someone else's house or home unless you're welcome or invited. The reason for this custom is to protect your spirit while you are on the land.

I'm a proud Ngunnawal woman as I carry my ancestors in spirit, walking into the future, teaching the next generations about the oldest culture in the world, my culture, the Ngunnawal Aboriginal culture. I'd like to pay my respects to my elders past, present, and emerging and extend that respect to First Nations people here this evening and online. But I'd also like to acknowledge all the non-indigenous people in the room as well as well as online. In keeping in the general spirit of friendship and reconciliation, it gives me great pleasure once again to welcome you to the land of the Ngunnawal people. And on behalf of my family and the other Ngunnawal families, I say, welcome, welcome. Thank you so, so much. God bless. I like presents. As long as it's not chocolates.

Fiona Burns: No. So I'd just like to thank Aunty Violet for coming and doing the welcome to country, and I've got a little present that I made for her, a basket on behalf of our family.

Violet Sheridan: Oh, thank you so much.

Fiona Burns: That's okay. Pleasure.

Violet Sheridan: Thank you.

Rebecca Bateman: Thank you so much. What a privilege to be, well, what a privilege that we've had today to spend the day with the family of Aunty Marg. But what a privilege to hear Aunty Violet of the memories that you have of Aunty Marge. And as I've said to the family today, one of the things that struck me as we've been working towards this event and as this book has been coming together, is that everybody I've spoken to about this has had a connection with Aunty Margaret Tucker. Whether it's remembering knowing her or meeting her, or whether it's just a heart impact that she had. It's really evidence to me and to everybody else who's been on this journey what an amazing human being she was, and the impact that she had on everybody that she met, and many, many, many people that she didn't meet as well. And today, that has been demonstrated through the legacy of the family, her grandchildren, great-grandchildren and great-great-grandchildren who we have had the privilege of being with today. And tonight is about celebrating Aunty Marg, and it's about celebrating you. And so I would like to, I've been asked to read out a little bit about Aunty Marg, the biography that appears in the book, and then I'm gonna hand over to the family to really give us an evening of celebration for your nan.

‘Margaret Tucker, who was known as Aunty Marge, is a revered and trail-brazing Aboriginal activist. Named Lilardia, meaning flower, when she was born in 1904, she grew up on the Cummeragunja Moonahculla Missions in New South Wales. The eldest of four children, on her mother's side, her family were Yorta Yorta people. And on her father's side, Wiradjuri. After a childhood spent surrounded by family, a culture on the Murray Edward and Murrumbidgee Rivers, at 13, she was forcibly taken from her mother's care and put into the Cootamundra Domestic Training home for Aboriginal girls. At 15, she was sent out to work as a domestic servant for white families in New South Wales, where she endured racism, abuse, and loneliness.

In the 1920s, Aunty Marge seized her freedom and moved to inner Melbourne, where she became a lifelong activist for Aboriginal recognition and rights. She was a founding member of the Australian Aborigines League in 1932, and a Victorian representative at the First National Day of Mourning in 1938, two initiatives that inspired and drove Aboriginal activism for decades. Aunty Marge was the first aboriginal woman appointed to the Aborigines Welfare Board Victoria in 1964 and to the Ministry of Aboriginal Affairs in 1968. She helped establish the first National Council of Aboriginal and Islander Women. And in this period of her life, she was guided spiritually by her involvement with the international Moral Rearmament Movement.

In recognition of her work for First Nations Australians, Aunty Marge was awarded an MBE in 1968 and published her autobiography, "If Everyone Cared" in 1977. She passed away at Mooroopna in Victoria in 1996, aged 92.’

What a remarkable woman and what a remarkable life. And more so that from the testimony of you all today and from what I've come to learn is that despite everything that Aunty Marge endured in her life, she never lost her compassion, her humanity, her gentleness. You've all made that so abundantly clear today, and her legacy lives on with you. So without further ado, I would like to hand over to Tania Rossi, who is the great granddaughter of Aunty Marge, and to Marcus Hughes to talk to us a little bit about how the book came to be and what that journey was like.

Marcus Hughes: Come on down. I'm sure there's things for us to play with. Yeah. Have you had to go with these?

Tania Rossi: No. That works.

Marcus Hughes: Oh. So while the old one gets comfortable, am I on? Was that a yes? Oh, thank God for that. Yeah, always challenged by technology these days. Today, we gather to celebrate a remarkable warrior woman. We've heard about her generosity. You look at the cover of the publication and you see a portrait that just is so full and communicates that business that we've heard about Aunt, about that generosity, about that incredible strength of spirit and generosity that we see in so many of our older ones. I've been lucky, I've been privileged to be able to work in situations where I can meet people who have incredible passion. Often, I meet with people that have remarkably unrealistic passion, who want solutions immediately. And that always presents great challenge. So I've been privileged to work here at the National Library. I then was invited to go and work at State Library Victoria to help establish the Victorian Indigenous Research Centre with another Yorta Yorta warrior, Aunty Maxine Briggs, who is so committed to ensuring that our folk have access to the cultural material that lives in these collections and the stories that are hidden.

So me as a Mununjali fella going down to work on Wurundjeri country. Not mine, histories. And having worked in New South Wales on Gadigal country and knowing those histories. And then one day, Max said to me, "Oh, Tania's gonna come in for a bit of a chat in a cuppa." I thought, "Yeah, fine, good. We'll program that in." So we did. And this is who I got to meet in a most remarkable way, because it was about cups of tea and just chatting. And this mad woman with this passion told me the story of her grandma and how she'd written her autobiography. Solid. But then there was this other bit that was about the editor of the publication at the time, doing a really severe edit that robbed the autobiography of its cultural, the cultural information that was buried in there and absolutely evident. And you know I guess when we started to talk, it was all about, yeah, another day in the colony and this is what we've gotta deal with and how do we make it so that Aunt's initial voice lived back in her story?

Unfortunately, State Library Victoria, who I love dearly, no longer has a publishing arm. So we have this important story to be told. We have this incredibly difficult process to go through of finding the people that will invest in the re-edit and the project and the concept. But I was really lucky that I had spent that time here and that I was able to look at Tania and to very confidently say, "I think if I use this, there might be someone in there that could be interested." And that's exactly what I did. I got onto the National Library Publishing team, told them about Tania's vision, and it was not a hard sell. It was welcomed by this institution so eagerly to continue that conversation. And that's what's really brought us here this evening is Tania's passion, the family's commitment, this institution's commitment to truth telling. And I'm just really happy. So thank you Tania for your patience and your perseverance in bringing another important story to life.

Tania Rossi: Thank you. You know as much as I would love to take all the credit for this, the journey actually began 28 years ago. And that was with a woman who deliberately chose not to be here today, which is a Dr. Jennifer Jones who did a thesis on Nan. And what happened, like most Aboriginal families, the parents that dragged the kids along to everything, meeting everyone. And that was my mom, my mom Maxine who, any event that was on in town, anywhere that we had to be, she'd just drag us along. And that's what happened with this. So we'd heard about this lady talking at Moral Rearmament and saying that this young woman, Jennifer Jones, was doing a talk on Black writers and white editors, which was a book that she ended up publishing. And so my mum's got me to come down with her and we were speaking to Jennifer Jones for a little while after she did her thesis and was talking about how she'd come across Nan's manuscript in the National Library and how she read the wording and how it was so different to the edited version of her book that was published. So she started conversations around wanting to get it republished and put Nan's wording back into the book.

Now at the time, she had contacted, so we spoke about it that night and she went away and then she'd contacted some people, asking to get into contact with family. They got in contact with my uncle, my eldest uncle. But at the time, he was living in Horsham. So he said, "I don't have the time or commitment to do it maybe speak to my sister Maxine”. So that's what she did. So she got in touch with my mum, and they conversed through letters, and that 'cause I don't even know if we had emails, back then then maybe. Maybe, I don't know if emails then, but my mom wouldn't have known how to use 'em anyway. So probably by phone. She contacted 'em with letters and that. So they started this with this friendship and they started talking about it and they'd started to have conversations around it. But then Jennifer had to move inter-state. And then my mum got sick. She was diagnosed with breast cancer. And so over the next seven years, it was kind of a little bit put on the back burner, sort of. So it kind of fizzled out there for quite a few years.

And it wasn't until I picked up my journey some years back now, and I was asked by Kimberley Moulton from the museum in Melbourne, and they were doing a big archive collection and they were putting some stuff together and they wanted a family member of Nan's to come in and read from her book and talk about her life in Kinnears in Footscray. So that kind of got the ball rolling, 'cause I'd bumped into Uncle Bobby Nichols at some space. And he was like, "Oh, Tan, we need a number, and people are calling me and blah, blah, blah, blah." So I gave him my number and that's sort of where it's all sort of stemmed from.

So yeah, so I met with Kimberley and we did this talk and we did the videoing. And I just got thinking, I was thinking, I wonder whatever happened to Jennifer Jones. And there is a quite a few little, being very spiritual people, little things started happening. Like I remembered when I was talking about Nan with Kinnears, I remember going into my back room and opening the cupboard to get down a bag of photos that my mum had. And this one photo fell down and landed face down. And I looked at it and it read on the back ‘nan at Kinnear's’, and I flipped it over and it was a picture of Nan Tucker at Kinnear's. And I was like, "Oh, that's a bit weird." That photo out of 100 that's in this bag fell out.

So I started thinking a little bit about how do I get in touch with Jennifer again. She had sent me a book that she'd published, but unfortunately, I lent it to one of my mum's friends who, which is really sad, ended up passing away too of breast cancer. And so I thought, “I don't know where I'm gonna even get her number from now”, but just little things plan out and things happen. And one day, I was going through an old folder of mine and I'd been through this folder many times and I was looking for something in particular and I came across a bit of folded paper. And for some reason, I just thought, “I'm gonna pull this piece of paper out, see what it is”. And it was the letter that Jennifer had sent my mom, and it had Jennifer's number on the bottom. And so I thought, “why not? I'll ring it. You never know.” And she answered. And she was like, "Oh my god, Tania. I was just thinking about Aunty Marge and I was thinking about your mum. And this is so uncanny."

And that's kind of how our story panned out for the last seven years is we started talking about the book. And there were, there was lots of things that had to be done to get it here today. We had to get copyright lawyers looking at it. We had to get other lawyers looking at it because of the photos and how we're gonna do the covers. And none of it was funded. So we were just pulling on people that we knew and pulling, especially Jennifer, she pulled on all of her university friends and all the other people who could get all this stuff happening. But it took time 'cause it was all volunteer and people were helping us. There was no rush. And we always say, me and Jennifer always have this little bit of a giggle, saying that, “it will be when it will be”. And I think it got a lot stronger last year with the year of the voice. And, you know it became, like imagine if the book got published, with the year of the voice and her voice being put back into her book.

Yeah, it stemmed from there. We had to get the copyright back to family. Mum had it, so we worked closely with Margaret. Yeah, just with everybody's busy schedules and trying to get it done, it took seven years. But it couldn't have come out at a better time because I think that the book is here now, and I think that it's a perfect time to be relaunching this book, especially in the year of the voice, especially where Australia sits today. And 1977, I don't think they were quite ready for the story or actually took the story for what it was. And now, we can put it back out there and I think it's time to be heard and her voice it’s time to be heard now. And it couldn't have come in a better time. And we were looking at the written pieces of paper today and we looked at one of the hardcover books and noticed that one of them was signed 1977, the fifth of the fifth. And we're like, "We're the 15th of the fifth today." So it's kind of like, ooh. A bit of one of those little things that align again.

So, yeah. And then with the family as well, this last like six months, we've been trying to get together what the front looked like, what photo we'll use, what sort of, me and my Aunty were sitting there with hundreds of photos, and then I spent the next month scanning every single one, collating it and putting names. So it's been a long process, but it's been a beautiful process. And it's also been a beautiful journey for myself to kind of reflect and particularly going back and doing my journey of the Wiradjuri side. It's been really, really amazing to go back and do that journey and go to where she went to school and go to Darlington Point in Warrangasda where she was born. So it's also been a really, really amazing journey for myself to have done this. And it's for, even for our family, our kids, our grandchildren, our great-grandchildren that we'll never meet, they'll always have this from all of us to keep passing down. And I think that we need to resurrect her again and put her out there full force because everybody can learn from her and her words. Absolutely. And then I met you and Maxine. That's why you were in the story too, weren't you?

Marcus Hughes: Well, some way.

Tania Rossi: Some way. You were actually one of the major things, 'cause we were actually struggling to find a publisher, me and Jennifer. So we'd had it already, and we were actually struggling to find a publisher, and then Marcus goes, "Well, you know what? I kind of used to work at the National Library. Maybe I can pull out a name." And next minute, we were online, and they told me, "Yes, we'll do it." And I was like, I said to Jennifer, I go, "Does that mean they're gonna do the book?" And she said, "Yes." We were on Zoom and I just started crying. It was just like, what? It's happening? Yeah, it was quite emotional. So you play a big part, and there is an acknowledgement to you in the back there as a thank you because we were struggling. We'd sent this off to about seven different publishers and either we didn't hear or it wasn't what they wanted to publish, so yeah, when the National Library and you came along and we got that, it was just like, "Yes, we got it."

Marcus Hughes: That's great. But all it took was a phone call, and I think that's something that's really valuable to remember. That when we are facing challenges or we have a passion to make something happen, all it took was a cup of tea.

Tania Rossi: Yep. And a yarn.

Marcus Hughes: I saw the passion. We had the yarn and the phone.

Tania Rossi: Yeah.

Marcus Hughes: Totally simple. So it's really exciting that the publication has been repaired. And we have changed that notion of another day in the colony to a really important bit of business that involves, yeah, absolutely, revoicing Aunt’s messages. But also, restructuring the way institutions operate and function. And that now, this material is valued by the whole community, not just by our communities. And Lauren, I'm sorry to do that, but are you here?

Tania Rossi: Oh, she's at the back there. Hiding near the big pole there.

Marcus Hughes: Lauren, could you come down for a moment?

Tania Rossi: Come on down, Lauren.

Marcus Hughes: And Lauren, you can have my seat for a moment. Yaama. Here you go.

Tania Rossi: Oh, she got chairs.

Marcus Hughes: Oh, you can bring a proper one.

Tania Rossi: Everyone gets a chair here.

Marcus Hughes: Okay.

Tania Rossi: Everyone used a car, everyone gets a chair.

Marcus Hughes: There you go. Which way? Ah.

Lauren Smith: What are you gonna do to me, Marcus?

Marcus Hughes: Ah. It won't be painful.

Lauren Smith: Okay.

Marcus Hughes: I promise. But Lauren, you've been responsible from that time we had the very earliest conversations to guiding through the whole process to make this thing possible. Probably your first major engagement with an indigenous text or a process of deep cultural significance for our folk. How was it?

Lauren Smith: Hello. I'm the publisher here at the Library. And so I was on the video meeting that we had with Marcus. I was one of the people that he called, with my colleague Stu. And I remember I cried in that first meeting. That's not a shock to anybody that knows me. And when that call ended for us, the conversation that you had with Jennifer, Stuart and I also had. Kind of amazed at the privilege that a story like this and an opportunity like this would come to us. And maybe you know this about the public service or about making books, sometimes it moves really slow and sometimes it moves really fast. And I think this is one of the fastest proposals that we ever put up and one of the fastest and most enthusiastic yeses that we ever received.

And for the Library, we were making this book at a really similar time that we were implementing an indigenous cultural and intellectual property protocol. And so a great deal of work was going on around the Library to think about how we participate and how we help raise up voices, about how we give back agency, about how we participate in this work in a really meaningful way.

And for our team in publishing, working with Tania and Jennifer and the family on this was profound. We really felt the depth of the responsibility. I think it terrified me some days a little bit to be involved, but it also felt like a privilege all of the time for me and for the whole team. It was remarkable. And I think every step along the way, trying to make sure that we were doing something that would honour Margaret and her work and the way that she lived. She was a really good role model to have before us as we went, and one of the things I've been talking with another colleague about this week, what she says all the time that her mother said, “be up and be doing”, this really felt like we were participating in that in a really beautiful way.

Tania Rossi: And you've been wonderful. I have to admit, well, but you did say, the public service and that's like, but when you send emails and when you have to communicate via email, a lot of the times, you don't get that quick response that you need and things pass over and you've gotta remind people and it's always delayed. But these guys, honestly, I think we were just like tennis. It came, and boom, we returned it. And it was just on this constant the whole way. If I had anything that I had issues with, I would just ring one of you. Between Lauren and Jeremy and Lori and the other Lauren and Rebecca, and there's three teams. So I did well remembering those names. But they were all on it. They were just constantly on it. They were all over it. They were very respectful. It was always about our wishes. It was always about Nan, it was always about respecting from the oldest to the youngest, the family members. And I couldn't have asked for anybody else more beautiful and better to do it than yourself. You did an amazing, amazing job and I applaud you for that. You guys have absolutely been amazing. With our busy schedules, you never once at faulted at ever returning my emails or getting back to me. So it's been amazing. So I highly recommend these guys. Ever. Absolutely.

Marcus Hughes: Thank you. Oh, thank you. Thank you, Lauren. Ah, whatever. Just pretend you're at home. I am. Now look, we've got a presentation, a PowerPointy thing with some beautiful images of art. And unfortunately for those who are joining us from their living rooms, because of all of that business around copyright and which bit of music you can play, when, why, how, and if, we can't livestream the sound to go with this, but I'm sure many of you will be familiar with it and you can sing along at home. The video, the sound that's being used for the video is the Yorta Yorta language song, "Ngarra Burra Ferra." And most of you will know it from the soundtrack to "The Sapphires." Thank you. How you going?

Tania Rossi: Good, mate, how are you?

Ngarra Burra Ferra You all going okay? Beautiful. Do we have any tissues in the house? Oh, bless.

Audience member 1: Just take a box.

Marcus Hughes: Oh.

Audience member 2: Can we ask questions?

Marcus Hughes: We've got a bit of stuff to get through, but I'm sure the family will be happy to answer any questions.

Tania Rossi: And these are all coming up here. So then we're gonna have Q&A.

Marcus Hughes: So Tania, would you like to invite your family to come and join us?

Tania Rossi: Absolutely. Come up here, you guys. So we've got grandchildren of Nan. So we've got my Uncle Darryl and my Aunty Barb, the grandchildren, who's the second eldest and the second youngest. Then we've got the great-grandchildren, the eldest great-grandchild here, Darren and his son, great-great grandson. I've got my son. Aunty Barb, here, you come sit here. And great granddaughters. I thought we were gonna sit here. Yes, absolutely.

Barbara Burns: Does anyone wanna sit next to me?

Tania Rossi: I'll come sit next to you.

Marcus Hughes: I think it's probably on. Mine was. Oh, somebody will come and help. Wow. So how many generations have we got here tonight?

Barbara Burns: Three. Grandchildren, great-grandchildren, great, great, great. So three.

Marcus Hughes: Great.

Tania Rossi: Just go use it.

Barbara Burns: How do you use it? You’re used to it. Oh, sorry. Three generations.

Marcus Hughes: That's three generations.

Darryl Burns: We all testing now?

Marcus Hughes: Yeah.

Darryl Burns: Hey. There you go. I'm on.

Donna Doherty-Hughes: Hello.

Tania Rossi: Now the show begins.

John Rossi: Hello. Hello.

Fiona Burns: Hello.

Darren Burns Jr: Hello.

Darren Burns: Test, one, two.

Marcus Hughes: There's always one.

Barbara Burns: Hello. Mine works.

Marcus Hughes: Great. For us older ones in the room, I think one of the most important and soul-filling things that I've been able to see in the last 20 years is the way that our young ones are taking up the mantle, who are making sure the stories continue and live on, who changed the systems so that we get a bit closer to the truth of the way we, in community, work, and what our values are. Here at National Library, I've got young Jeremy, who I've worked with for well over a decade. And last year, Rebecca sent him to Hawaii to represent at the Indigenous Librarians, sorry, the International Indigenous Librarians Forum. And to be able to see that growth in our young ones is the thing that lets us sit back and relax and know that the future is safe and secure. So I wonder what Aunty Marg would be thinking now, seeing the work of you lot as family, making sure-

Barbara Burns: She would probably crack us with a walking stick because she didn't like attention for a reason. Oh, sorry. She’d probably crack us all with a walking stick because Nan was very, she didn't like the spotlight on her. She done this because it was who she was. So yeah, she'd probably look at us all and say, "You're gonna..." Yeah, she was never one to put herself up here. She just was herself.

Darryl Burns: But at the same time, I'm sorry. Sorry, carry on.

Darren Burns: Just to touch on what Marcus said, I think the generations always had a voice. I think it's now that society's given us more of a platform and we're being heard more. So the younger generations have got the platforms that we the older generations didn't have. So I think that's why we're being heard a lot more as a younger generation. Those times in our time, we didn't have that. Our voice was silenced, but now, these younger generations have been given a platform to have that speech.

Marcus Hughes: Yeah, and it's so good to see.

Darren Burns: Oh, absolutely.

Marcus Hughes: So young fella.

Darren Burns Jr: Yeah, mate?

Marcus Hughes: You've got a busy way ahead.

Darren Burns Jr: Yeah, well, it's like anything, I guess, if you do something that you're passionate about, it's not really work. I think, as Aunty Barb said, Nan didn't really do anything for the applause, it was more so. But within family, we've always been proud. It's always been, she'd never really had to, we kind of did it for her. Like I remember back in grade four when we had to do a famous Australian project at school. I'd done mine on my nan, and a lot of kids in the classroom like, "Who's this? I never heard of her." Like people doing Adam Gilchrist and Sir Donald Bradman, and I've done Margaret Tucker, so yeah. So I think within our family, we've always been proud and she's always been someone that we've always looked up to. Couldn't be any prouder, really.

Marcus Hughes: That's great. And I guess we always have conversations about the weight of culture. And it sounds like it's a laborious responsibility to be good Black voice. But then there's that business about the ways of being that have been shown to us by our old ones are such practical guides around how to be and how to live with community for a better place. When spending time with Aunt, when you were bubs, what was that like?

Darren Burns: Growing up, knowing , I was lucky to sort of spend a lot of time with Nan when I was younger and visited when she got older with her Alzheimer's and stuff like that. That was very sad times and unforgettable times. And as I learned more about dementia and Alzheimer's, I realised that probably the last seven or eight years, she sort of relived the traumas of her life, 'cause she kept saying about the coming together, the policeman. And so at the time, I didn't understand as much, but as I've grown older and working in the health industry, I know now more about dementia, Alzheimers, was called back then. And to really understand that that trauma that she kept reliving was really, doesn't sit well with me now because I didn't realise at the time. But growing up, like her values and the harmony she had and the respect she had for anyone, didn't matter what colour, race, what economics that you come from. She was like, her doors are open to anybody and everyone. And after all the stuff that she's been through in her life, she had mercy and she come up from to be so open and the gentle soul she was and the harmony she showed for everyone was just, and I think it's set the family in good stead to carry on that legacy.

Marcus Hughes: Sometimes, it's really hard, isn't it, to actually realise the impact that people have on our lives. I still think about my nan when you were talking there, and I was under the sewing, the tread old sewing machine, 'cause my nan looked quite a lot like Aunt. And when you're so close to someone like that, that then has this incredible impact on a broader stage, it's often hard to realise how much Aunt may have touched other people's lives.

Darren Burns: Yeah, I think as a teenager growing up, I know I sort of took her for granted. But as I've got older, I sort of realised the effects she had on my life. And one of my mates at work read the book, and he said, "Now I understand you. You're your grandmother." So I didn't understand it at the time growing up. It just, as I said, this impact she had on us, we just sort of followed in that footsteps without acknowledging it. But now, I've sort of had time to reflect on it, you realise that, yeah, she did have a huge impact on my life. Darryl, somebody else?

Darryl Burns: When you look at it, I think she had an impact on all our lives.

Marcus Hughes: That's great.

Darryl Burns: I grew up with Nan ever since I was born sort of thing. What she's put into us, it is just pure love, you know? And the family, the family, we’r brothers and sisters, we'd have our now at each other and what have you. But there was so much love in the family. If anything went wrong with one, it was all in or nothing. And you touched on before about what Nan would, what would Nan feel about what's going on today. She wasn't into, this didn't affect her much, like the limelight and that. But the thing she would be really proud of is-

Barbara Burns: Seeing her family sitting here as one. He's gonna break-

Darryl Burns: And all now knowing her story.

Barbara Burns: She’s gonna cry too.

Barbara Burns: I can tell you a little story about my grandmother, the kind of lady she was. We had neighbours and the father passed away. And the mother, she had a bit of a disability and she had seven young children and welfare stepped in to take the children. Well, Nan said there's no way you're taking those children. So she actually moved in with that neighbour so that welfare wouldn't take ‘em. And I think it's because she was taken away. So there was no way she was gonna let those children be taken. So to this day, the Dentons, they're still like family to us. And so that was the kind of lady she was, the woman she was.

She was very compassionate and just thought of everybody else. And what the book said, she really did care. So yeah. And we are very proud of her, and it has inspired us all. I've done aged care and disability because I wanted to just be there for people and make 'em a little bit more comfortable. And that all comes from Nan, the warmth and the compassion she showed. So it's affected all of us in our work in a lot of ways. A lot of ways, so yeah.

Tania Rossi: And I think you're right, Uncle Darryl, that with Nan, that if she could actually sit here in the front row, she'd be like, "My goodness. My great, great grandchildren are here talking about me." She'd be blown over. And the fact that their children will have her name on their tongues as well going forward would blow her mind, I think. Because if there's one thing we've done, we're like any other family out there, we have our trials and tribulations, but we've always stayed connected. And I think that comes through with Nan's story that we won't let that happen to any of us to be disconnected and not have that family unit between us all. And you know we all live far from each other and that, but we come together every time and we're having our family reunions every year now. We have been for so many times. We know it's important to have that connection.

There's two people I wish was here today, and that's Darren's dad, Michael Rodney, 'cause when I got the book in the mail, he's probably the first person I wanted to call, but we lost him last year. Because anytime I needed to do anything, I needed some guidance, like a push, I’d call Uncle Rodney and say, "Hey, Uncle Rodney, what do you reckon? You reckon I can do this, that?" Like, "Yeah, yeah, absolutely. You got my 100%." And then I talked to Barb and Uncle Darryl. But he was a real solid rock for me.

And of course my mum who started this, I say she started it, and to have finished it for her. This is nothing about me, this is about my nan's book and it's about finishing something for my mum because she would've absolutely done probably even more than me to get this out there faster if she had the opportunity. And it's for all of us because you know they handed it all down and we carry these stories. And my children weren't even born when Nan was alive, but have made comments. I think my son said to me, when he was 10 or 12, "Mom, I never met Nan Tucker, but why do I feel like I know her so well?" And it's just because it's spoken about, it's keeping them alive, it's telling these stories. And if we don't do that, then my great, great grandchildren that I'm never gonna have the privilege to meet will never know this beautiful story.

Darren Burns Jr: Yeah, we spoke about that. When this all come about and I was asked to come up, I had a phone call with yourself and we spoke about it. And books like this as well as there, to celebrate that, like the amount of culture in that that has been lost in the last 50 years, to pass these stories on, it's important not just to us, because if we lose that amount of culture again, well, we're not really gonna have a lot left. So it's funny. You always hear Aboriginal people, we didn't really write books or anything like that. So me growing up, to have a great, great grandmother that wrote a book, it's like, "Hang on a second. We do write books." So yeah, nah, it's awesome to keep those stories going to pass on to my kids and their kids and so on and so on. I think the legacy itself, it's truly amazing.

And yeah, if you haven't read the book, well, I highly recommend doing it. Myself, I read it when I was a bit younger, and I didn't quite get the messaging as much until I matured and went through some life experiences myself to really recognise how wonderful and amazing she was, to have the outlook she had on life after all the pain that she was dealt. It's very easy to get caught up in the world and do the “poor me, poor me”. But when you read someone's story like this and you see what they did with their life, it's that kick in the butt that you might need sometimes to say, "Hang on a second. You don't have it that bad, get back on”.

Tania Rossi: You're 100% right, 'cause that's what it is here. When we've had some of my toughest days, I'm like, "What are you wincing about? Just think of Nan, think of Nan Molly, think of Mum, think of all that intergenerational trauma." And just like, "If they can do it, you got it, Tan, and just keep going." So they're who I go to every time things get tough, and they just push, because if they can do it, we can do it too. Yeah, it's a very big message there.

Donna Doherty-Burns: That's right.

Darren Burns: And if you have read the original book, you only know part of her story. This will tell the whole story. The original book tells part of her story, but this is to tell her story.

Donna Doherty-Burns: And if you just met her, honestly, you would've loved her. Like she never had a single, yeah, she was just a lovely woman. She never, yeah, criticised anyone or anything like that. She was just sweet to everyone. Whoever she's seen, she always brang 'em in. I remember when I was a kid, we used to go to her place. She used to pull out 20 cents, all that. And the shop's just down the, yeah. Not far, it was only a minute walk. Go buy 20 lollies for 1 cent. Come back, yeah.

And I'm proud. I'm proud 'cause my kids, like I've told ‘em all about her. And yeah, they watch her at movies and all that. They read her books, and yeah. And now, they're doing the same. They're in the culture and they do things and that, and I'm very proud of my kids, because they're gonna be like her. Yeah. They're gonna be smart and do this, yeah. Hopefully, do the same thing that she done. But yes, I miss my nans and my aunty, my uncle and that, but we've gotta do it for them. So yeah.

Marcus Hughes: Thank you for that. We're running a little earlier than we'd normally planned.

Tania Rossi: We can talk.

Marcus Hughes: Keep talking, go on.

Barbara Burns: What impact did nan have on you? What have you achieved? What you got around your neck, Donna? You gotta stand up and show that.

Darren Burns: Stand up, Donna.

Barbara Burns: Share it up, come on. Up you get. Show them all, what's that?

Donna Doherty-Burns: Gold medal.

Darren Burns: From where, Donna?

Barbara Burns: For what?

Donna Doherty-Burns: Back in '92. I was 19 years old. I turned 20 in Madrid, Spain for Basketball Paralympics. Thank you.

Tania Rossi: And she got that before Cathy Freeman and before Nova Peris. And I tell people that all the time 'cause it's never recognised 'cause she was in the Paralympics. So that's an achievement.

Barbara Burns: And Darryl, what award have you got? Oh, no, you haven't.

Darryl Burns: In Tania's purse.

Barbara Burns: That's not yours. Do you wanna show-

Darryl Burns: You wanna show that?

Tania Rossi: What do I? Oh yes, I forgot. It's not mine.

Barbara Burns: Geez, I'm the old one and my mom's got adventure. They forget, I don't.

Tania Rossi: No, there's a story to that, 'cause there was something else in my purse this morning that wasn't meant to be there. So when he said something's in my purse, I'm like, "Oh no, What did they put in my bag?” Here, you show it. It's your nan's.

Barbara Burns: All right. Do you wanna hold this? Okay, so you all know that my grandmother got the MBE medal, so we just brought it along today. That is the MBE, her MBE medal. And there's a letter here if you wanna read that out.

Tania Rossi: Oh, which one?

Barbara Burns: The letter, not the card. Okay, so this is the MBE medal. I'll let Tania read this.

Tania Rossi: Why can't someone else read it? Fiona, do you wanna read?

Barbara Burns: You're good at talking.

Tania Rossi: Who's clapping?

Barbara Burns: Oh, it dropped. I dropped the thing.

Tania Rossi: Oh, you dropped.

Barbara Burns: You pick it up I’m getting old I can’t bend over. I'm just embarrassed.

Fiona Burns: Brag about it.

Tania Rossi: Something cheeky. She's saying stop embarrassing me now. So this is the letter that came with, and it said, "The Secretary has the honour to transmit a warrant of appointment under the Queen's sign manual, Queen's sign manual to the most excellent Order of the British Empire and to request that the receipt of this warrant may be acknowledged on the attached form. The Secretary would be glad to receive notification of any change of permanent address. And in the event of the deceased persons holding such warrants, executors are earnestly requested to notify the Secretary. Margaret Elizabeth, Mrs. Tucker, MBE." But the other card states that if you are a holder of this medal, if deceased, it's yours for lifetime. So we didn't wear it because it's a bit frail and some of the cotton, it kept falling off. So we didn't wanna lose it.

Barbara Burns: Anyone wants to come and have a closer look, feel free.

Tania Rossi: There you go. She said feel free to come have a look. They won't charge you. I won't let her charge you either. You can come have a look.

Fiona Burns: Uncles charge. And miss an opportunity?

Marcus Hughes: Oh, what a delightful moment or seven. Thank you so much for being willing to come and join us this evening and share your stories with the people that are gathered here and gathered online.

Barbara Burns: Well, we'd like to thank everyone here for turning up. It just shows how much our grandmother is loved and known. So thank you, all.

Darryl Burns: And I gotta apologise for the way I break down, because whenever I talk about my grandmother, because I was with her virtually from birth, until late teens, early 20s. And when I talk about her stories and that, it's like I'm talking to her and I can see her face.

And also, I got a good friend in the audience here, known over 60 odd years, Mr. Andrew Lancaster. He knows Nan real well. We also taken to MRA House and met the American Indian Chief Walker in Buffalo and like we're only kids in back them days. One of your games you played was Cowboys and Indians, and meeting a real life American Indian, and a chief at that. What was he, Sioux? Sioux or Navajo or-

Andrew Lancaster: No, it was Western Canada.

Darryl Burns: Western Canada?

Andrew Lancaster: Yeah.

Darryl Burns: Oh, well, he wasn't American Indian. He was on the other side. But he was still, but no, it was really nice seeing you, Andrew, and your wife, yeah.

Andrew Lancaster: I was just remembering with meeting Darryl. This is wholly unrehearsed. When I met Darryl for the first time in 65 years, tonight, I reminded him of when he came with his brother Alan, his older brother, to spend a weekend with us in Melbourne. So you lived in Broadmeadows and we lived in Box Hill. And we had an absolute ball. We played ping pong endlessly on the dining room table. Quite a small table. But then Darryl surprised us all by showing us his attempt at tap dancing. And it was absolutely fantastic.

Darren Burns Jr: He's gonna give you a demonstration right now.

Darryl Burns: Ah, those days are gone.

Barbara Burns: Music's gone for you.

Darryl Burns: My dancing days are over.

Fiona Burns: How many women were there?

Darryl Burns: Oh, there must have been 50 of them.

Fiona Burns: Oh, there was a thousand before.

Andrew Lancaster: Anyway, a couple of years ago, just to finish the story, well not finish it. Come to the next chapter. About two years ago, I had a sort of an, this was all before the voice that was being discussed and the Uluru Statement from the Heart and so on. I thought to myself one morning, “I really would like to reconnect with Darryl and Butch” as we called him, Alan. And it took about 18 months to find them. And you were the person, Barbara, who gave me the phone number of Darryl here.

Barbara Burns: Don't hold that against me though.

Andrew Lancaster: No, I don't. Full of gratitude for that. And we talked for about 45 minutes on the phone and then you put me in touch with Alan and we talked on the phone. And since then, I've been to Alan's home in Mandurah in Western Australia. So that's been a great enrichment to our lives.

Darryl Burns: That's been, what, 60 odd years?

Andrew Lancaster: I'd say about 65 years.

Darryl Burns: Whoa, yeah, easy, easy.

Barbara Burns: You're that old.

Andrew Lancaster: So we were young. And your memory is amazing because you asked about Vincenzo, who was an Italian Australian who lived down the road about the same age. And we got up to all sorts of mischief, I think

Darryl Burns: We did.

Andrew Lancaster: Anyway, we won't go into that.

Darren Burns: He hasn't stopped.

Darryl Burns:But we always blamed it on Vince.

Barbara Burns: There's something I wrote, and I just wanna finish off. I won't say anymore, can I say, but I wrote this at the dawn service. I'm gonna let Tania read that 'cause I'm gonna break down 'cause I can't read.

Darryl Burns: That's what they call passing in the buck.

Barbara Burns: It's sentimental. So this was what I wrote for the dawn service, but had a big impact on a lot of people. And it's just how we feel about our grandmother.

Tania Rossi: My grandmother, Margaret Tucker, was an activist, but what I really would like to leave with you today is who she was at her core. Many have heard of her and know of her as Margaret Tucker, but so many more know her as Aunty Marge. She was a mother, a grandmother, great-grandmother and an auntie to all. She's left such a massive imprint, not only in my life, but in the lives of many people she has met on her journey throughout her life. Those of us that were lucky enough to have known her remember her for her kindness, the love and the warmth she took with her wherever she went. To Nan, everyone was family. Everyone was equal. I know my grandmother has proven that one person can make a positive difference in lives of so many for generations to come. Our actions do ripple through into the future, and what a ripple of love she's left. A lady I am so proud of, my grandmother, Margaret Tucker Lilardia, MBE.

Marcus Hughes: Oh, thank you for those words. I might now invite Rebecca to come back and wrap up the evening for us.

Tania Rossi: Rebecca, can I just say one thing before you wrap it up? I actually just want to thank Aunty Violet here for having us on your country today. We have all come from Wurundjeri. Where have we all come from? Bunurong? Where's your country?

Darren Burns Jr: Wadawurrung.

Tania Rossi: Wadawurrung. We've all come from all over in Melbourne to come to your country today. So thank you very much for having us here. And your elders and people, we acknowledge them and respect them and thank them. Thank you.

Darren Burns Jr: Can I just say one more thing real quick too?

Donna Doherty-Burns: No.

Darren Burns Jr: To you, Aunty Tan. I just wanna thank you. Yeah, like the work you've done to make this happen is amazing. And for someone like myself who never really got the chance to meet Nan, we live on through our stories. So thank you for giving me an opportunity to get to know her a little bit better by knowing her words. It does mean a lot, so thank you.

Tania Rossi: Oh, sweetheart. Oh, she's here with you.

Darren Burns Jr: Thank you.

Donna Doherty-Burns: Yeah, I would like to thank the ladies today for helping us-

Barbara Burns: Everyone.

Donna Doherty-Burns: Yeah, everyone, yeah.

Fiona Burns: I'd like to thank everyone that got the book together and brought it back for us to be able to have the proper version that we can read. Yeah, just to know her words properly.

Darryl Burns: And you people too for coming. We thank you very much from the bottom of our hearts. We do. Thank you.

Darren Burns: And a huge thank you to the National Library for taking in, endorsing this book, and making this happen for us and putting this launch on for us today and inviting everyone to come and inviting us up here and giving us the opportunity to speak about our great-grandmother, grandmother, great-great-grandmother. So huge thank you to the National Library too and all the staff.

Barbara Burns: Now, you wanna send us back home on the plane now. We had enough.

Rebecca Bateman: I do not wanna stop this, but unfortunately, we do have to. We have a building that will close in a little while and we have some, whoops, that was timely, wasn't it? And we have some roadworks happening outside, and I don't want anybody to get stuck in the car park overnight if we can avoid it. But I'm sure you'll all, we'll hand over to Tania in just a moment to take us out with a reading from the book.

But before I do so, from the bottom of my heart, thank you all so very, very much for your generosity. And it has genuinely been, I've been in this job now for a little while, and this has genuinely been one of the most beautiful things I've done. I’ve really, spending the day with you has been an absolute, an utter privilege. So thank you all so very much. Thank you everyone for coming. And thank you Aunty Violet for coming and welcoming us to your beautiful country. I'm sure you would all like to join with me in expressing our thanks and gratitude.

I'll ask Tania to come and read from the book, and after that, we will head up to the foyer. The family will be around there. We won't have any, we won't have time for questions down here, but feel free to come up to the foyer with us. And if you would like to have a chat or ask any questions, you can do so up there when we head up there. So I'll hand over to Tania.

Tania Rossi: What did you say? Always gotta be cheeky. I hope Nan is watching. Hope she turns the lights on and off on you tonight. Mucks around. Yeah, that’ll scare you.

Barbara Burns: I'll tell you some more.

Tania Rossi: Oh, don't you worry about that. I'll put me headphones on. All right, so this is from Nan's book. Me and Lauren went over and we thought it would be a nice way to end things and to have a few words that she put in her book. So this is Nan's words. And in her words, it hasn't been edited at all.

"All my life, it has been a joy to do things: from getting a sum right in school to taking a pretty nankeen, in brackets crane, feather to a young school teacher. But if I had to own up to a wrongdoing, no matter how small, I'll ponder over it for days. Then it would get too much for my conscience, and I would have to be honest. For most of my life, I have tried to pitch in and help with this and that. It has been fun. It has been a fun and natural way of life. I try to fathom why one would want to be the top dog. I suppose it is fear of losing prestige. Why is jealousy, envy, bitterness, and hatred created? I've gone through all these miserable feelings and realised one can be so selfish and cowardly. My biggest fear in life is doing the wrong thing, because I'm not happy until I put things right.”

“It is amazing what is happening now compared with 40 years ago. The Aboriginal Health Centre and Aboriginal Legal Aid are doing their best. I cannot help thinking that prevention is better than cure. The answer to all the misery in the world is absolutely honesty, is absolute honesty, unselfishness, purity, love, and care for all people from the heart. A man died on the cross long ago, giving up everything to show the way. I know people today who are trying to do the same.”

“Call it what you like, but deep in my heart, I do believe in the Holy Spirit, the good spirit, the wonderful spirit that has neither hate, bitterness, class, or creed. Everyone has it in their heart, deep down, if we only skim all the scum off and get rid of feelings of bitterness, hate, and the feelings of hopelessness like I've been having in the last few years. I try to keep out of mischief and to do what is right for the rest of my life. In this, I'm guided by the story Pastor Sir Doug Nicholls told in church one day about a black American preacher who said, "You can play a tune of sorts on the white keys of a piano. You can play some sort of tune on the black keys. But for perfect harmony, you must use both." I got that point, and it is a terrific one."

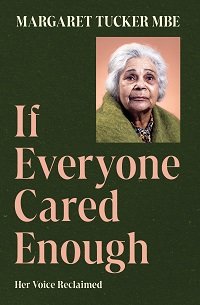

A celebration of Margaret Elizabeth (Liliardia) Tucker MBE (1904-1996).

Join members of Margaret Tucker's family for a celebration of Margaret's life and work, and to mark the release of the new edition of her autobiography, If Everyone Cared Enough.

About If Everyone Cared Enough

Margaret Lilardia Tucker MBE was a significant Aboriginal activist and one of the first Aboriginal women to publish for mainstream audiences. Her landmark autobiography – If Everyone Cared – has been republished by NLA Publishing in a new edition titled If Everyone Cared Enough. This nationally significant publication aims to reinstate the original words of Aunty Marge, as she was affectionately known, and shed light on the previously omitted descriptions of her culture and personal experiences.

Originally published in 1977, If Everyone Cared was a groundbreaking work that required significant alterations to cater to non-Indigenous readers who had limited knowledge of Aboriginal cultures and the consequences of settler invasion from a First Nations perspective. As a result, Tucker's tone and content were modified, and her original storytelling voice was altered.

If Everyone Cared Enough draws from the handwritten manuscript held in the collections of the National Library of Australia, allowing readers to experience Tucker's story as she originally wrote it. The republished autobiography commences with her joyful early memories of swimming, fishing, and learning, but also delves into the abrupt end of her childhood when she was sent to the Cootamundra Domestic Training Home for Aboriginal Girls. Tucker fearlessly recounts the horrors of the training, the cruelty of her first employer, and the profound loneliness, homesickness, and heartache she endured.

Throughout her life, Tucker remained dedicated to fighting for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander rights and opportunities. In 1932, she became the treasurer of the Victorian Aborigines League, one of the country's first Aboriginal organisations. Her tireless efforts were recognised when she was awarded an MBE in 1968.

This autobiography serves as a testament to the resilience and determination of a remarkable woman who overcame immense hardships to achieve recognition for herself and her people. The new edition includes photographs featured in the original edition, as well as new images supplied by Tucker's family, and a foreword from The Hon. Linda Burney MP.

‘Aunty Marge’s book had a profound effect on me when I first read it,’ said Minister Burney. ‘Aunty Marge’s original book was a valuable step towards the kind of truth-telling we look to embrace today, working towards reconciliation, and a deeper understanding of our shared histories. This edition is her truth and an important story to be heard by all Australians.’