*Speakers: Marie-Louise Ayres (M), Amy Remeikis (A), Katherine Murphy (K), Patricia Karvelas (P)

*Audience: (Au)

*Location:

*Date: 29/11/22

M: Women journalists were a challenge to society. They defied gender barriers by working in a stubbornly male profession. When obstacles were put in their way they developed new ways of reporting, new ways of writing. They made men in power, military leaders, politicians, media magnates, their own husbands uncomfortable and importantly they let a new audience of women readers know that the news was for them too.

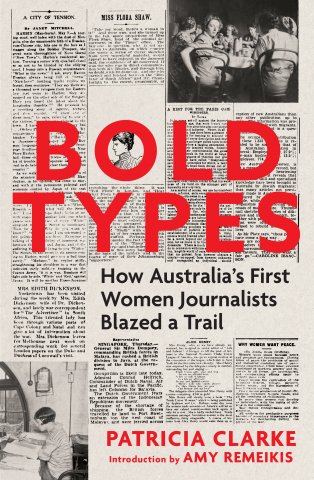

Good evening, everyone, a very warm welcome to the National Library of Australia and to this very special launch of NLA Publishing’s latest title, Bold Types, how Australia’s first women journalists blazed a trail by Dr Patricia Clarke. I’m Marie-Louise Ayres, Director General of the National Library of Australia.

As we begin I’d like to acknowledge Australia’s first nations peoples, the first Australians as the traditional owners and custodians of this land and give my respects to their elders past and present and through them to all Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

Thank you for attending this event either in person and there’s so many of you, it’s a delight, or online coming to you from the National Library on beautiful Ngunnawal and Ngambri country.

Bold Types tells the story of women journalists in Australia covering the period from 1860 to the end of world war 2. Tracing the journey of more than 13 independent, adventurous women who ventured far and wide and fought for relevance and gender equality together these stories illustrate the gains made and setbacks suffered by women journalists over nearly a century. In each story their tenacious determination and courage shines through.

Bold Types author, Dr Patricia Clarke, was a trailblazer herself as the only woman on the Melbourne staff at the Australian News and Information Bureau in the early 1950s. A writer, historian, editor and former journalist she has written extensively on women and Australian history and the history of journalism.

Now I’ve known Pat for nearly 30 years and in that time she has singlehandedly rescued so many Australian women from obscurity, poets, novelists, governesses, journalists and more. Her research day after day after day in this and other libraries has brought these women back into memory where they belong.

In 2001 Pat was awarded the Medal of the Order of Australia for services to Australian history and she is an Honorary Fellow of the Australian Academy of Humanities. Bold Types is her 15th book. Pat is with us in the audience tonight. We seem to have a beautiful little spotlight right on Pat in the back left of the room –

Applause

Thanks so much for being here, Pat, and also to her daughter and sons and family sitting around her, thanks for being here on this really special event for Pat and for us as a library.

Now we’re excited to have three bold types with us tonight to discuss Pat’s book. Plenty of bold types in this organisation, can I say too? Amy Remeikis, Patricia Karvelas and Katherine Murphy. Amy Remeikis is a political reporter for The Guardian Australia. She writes on major political issues in Australia, crime, the courts and the environment and she wrangles babies. I’ve offered to be chief baby wrangler so if you don’t remember I said I can wrangle babies if you need one. She’s a regular panellist on the ABC’s Insiders program and was the inaugural nominee for the Young Walkley Awards.

Patricia is a prominent and highly respected award-winning Australian journalist, television and radio host, podcaster, political journalist and commentator. She currently presents Radio National’s RN flagship radio current affairs program, RN Drive.

Katherine Murphy has worked in the Parliamentary press gallery since 1996. She’s currently – that’s a long stint too – she’s currently Political Editor and Canberra Bureau Chief of Guardian Australia and the host of the Australian Politics podcast. Katherine is a two-time winner of the Paul Lyneham Award for Excellence in press gallery journalism and Walkley Award winner for political commentary.

Please join me in welcoming Amy, Patricia and Katherine to discuss Bold Types.

Applause

A: Thank you so much for that lovely introduction and thank you to everyone who is here and watching this presentation. As you can see for women journalists the juggle still continues, often you’re finding yourself multitasking, doing a lot of things for home as well as at work so that’s one thing that hasn’t changed. That’s the thing that really struck me about Pat’s book and I was so, so honoured to be asked to write an introduction for her book because she is incredible as I’m sure everyone in this room knows. But then I was very quickly ashamed after I read her book because I did not know about these women who had come before me and who had blazed this trail, Patricia included, but I did not know the history of my own profession. I knew about a lot of the men, of course, but I didn’t know about the women and I walk the press gallery every day and there are photos of old press galleries on the wall and you just see men and men and a lot of white men and then occasionally you see a woman.

And I remember going past it a few years ago and I saw a male colleague giving a tour to some friends and pointing out the historical photos and somebody said oh who is this woman? And he said probably the typist. And that’s the attitude, you know, that’s why we don’t know about a lot of these women and that’s why Patricia’s book is so important. But it also struck me just how many of the themes are universal and remain with us today, how many of the challenges that these women went through are still with us today and that’s what I wanted to talk to Patricia and to Murph about, about what it is like being a woman in the press gallery in 2022 and how some of the same things that we hear all of these trailblazers going through in having to hide their lights under bushels or fight very, very, very hard to have even a modicum of the same amount of credit as the men or the sexism in the workplace or not being heard, being ignored or having a story and having it not being treated the same by your editors as somebody with a penis. So I wanted to talk to these amazing women about that so I will start with you, Murph. How would you say that reporting has changed for women in the press gallery since you started to now?

K: Well as was noted in the introduction I did arrive in the press gallery in the mid-‘90s which is equivalent to the Jurassic period, I suppose, but yet still here I am. Has it changed? Well in a structural sense it’s changed a lot because the environment that I arrived in in 1996 was – we didn’t realise it at the time but it was really the end of the print era or the beginning of the end of the print era and I’m a career print journalist. So it’s – things changed in a structural sense sort of slowly at first then it accelerated massively as I hit my first decade in the press gallery and then my second decade in the press gallery’s been sort of coming down the mountain of that disruption and by disruption I mean the rise of the internet and what that’s done to our practices and our business models. But Amy’s really asking me about culture, I think, rather than the practice of our own job although the two are linked always because you know the digital environment has ushered in – well has been a sort of reboot, rebirth of stylised misogyny in other forms.

But in terms of the culture I feel very lucky, the bureau that I arrived in in 1996 was The Australian Financial Review. It was run by a man but he was a very benevolent emotionally intelligent person who encouraged that culture in the bureau so a lot of women of my generation have had far more searing experiences than me in terms of the sort of male, female dynamics in newsrooms. By some amazing miracle I’ve not had a lot of that in a managerial sense. Some newsroom cultures, and I’ve worked now in a number of newsrooms, are very different, they are very, very different and there are different dynamics in them but obviously though while I feel very fortunate to have been hewn and mentored in a very collaborative set of cultures obviously there is still a very male-heavy dynamic in the press gallery and in fact I think it’s gotten worse since I’ve been there rather than better. I think the press gallery I arrived in in 1996, there were many more female leaders of bureaus than there are presently and I don’t really know why that’s changed, I don’t know why the gender balance has shifted but it’s certainly very male-dominated now in terms of senior positions.

We did I think culturally have quite a year in the year leading up to the election. Obviously I will be very careful about how I discuss that for obvious reasons but let’s just say there was an event that generated a reckoning that basically engaged political journalists in Canberra in very different ways. I think it has been noted publicly that a number of women in senior positons, political editors, bureau chiefs, decided I think - we didn’t have a secret meeting out in the corridor and compare notes about how we might confront the issues that we were called upon to report but I think collectively we reached a point where we intended to use our positions and our influence to generate a debate that would flow through the country. And I feel very privileged to have been in a position where I could do that. And I tell you what, I thought I’m going to get one chance, I’m not going to miss. And I know a number of colleagues felt the same.

So that was interesting. I think it made some of our colleagues uncomfortable. I think some of those colleagues remain uncomfortable but I think it was a very important thing to do and also important to sort of – you know it’s sort of like you know when you put your fist in a bucket and that – and the water level changes and then you remove your fist from the bucket and the water takes a little while to stabilise. I feel like we’re in one of those periods where we’re sort of settling on the other side of that. But I think that was important to do most importantly for women in the country but also for women in Parliament House in a variety of roles.

A: PK, you’ve taken a different path with your journalist career moving from newspapers to radio but always having to push against the tide and always covering issues that spark a lot of national debate. How have you found your journey navigating that, particularly since as one of the figureheads of Australia media you do become a target and do you think your gender plays a role in that?

P: Yeah so like Katherine but a decade later I arrived in the Canberra press gallery in 2003 and I remember very, very much thinking – and I’d always aspired to wanting to go to Canberra but feeling like not many people there were like me and feeling a very strong sense of being an outsider from the moment I arrived there and not knowing quite how to reconcile being my real self in that space. And that’s a bit more multifaceted so yes, I’m a woman, I’m also gay and I found that that space was very, very homophobic and when I think about some of the things people said to me I cannot believe I let that happen but I’m still kind of reckoning with that myself. And I also grew up in a very working class suburb where I had never met a journalist until I started working as a journalist, I didn’t have anyone to look up to where English wasn’t spoken at home so I found the press gallery to be a space which did not look like where I grew up or did not – I did not feel like – I felt like it was hostile to the sort of person I was.

So the way I dealt with that and back to you know navigating all of that is to try and fit in, to fiercely try and fit in. And I think about that toll that takes on people when you’re always trying to fit in and – and the kind of way that it limits your own growth and I think if we look at how things have changed, and I don’t think we’re living in a utopia at all, but I do think that people now have more opportunity to bring themselves to work and therefore in terms of the issues that you might cover and the interests that you take for it not to be something to be embarrassed about. So I think you know when we’re seeing journalists of colour who take an interest in the way racism might – and policy around race affects them, I think it does matter that somebody has a lived experience of something.

So we’re having our own conversation as journalists about the impact of that. Now when I started as a journalist I was told to put all of that away, that that had nothing to do – and in some ways to behave like or be like the men that were sometimes my mentors and I too, like Murphy, Katherine Murphy, had lots of – Murph – had lots of mentors that were men and did try to help me and I had lots of experience of toxic sexual harassment that I endured at work too. So all of these – sometimes all of these experiences sometimes happen in one day. This is the thing like life is fluid. And sometimes a lot.

You know as I’ve navigated my way through my career I think – I look at women in their 20s now who are younger journalists and I still think they have – they deal with lots of sexism, don’t get this wrong but I think wow, that’s so cool, I wish I was her because in my 20s I was always trying to minimise the things that made me different, always trying to minimise them to make other people comfortable. And when we look at you know Patricia’s book and the stories of women who were trailblazers I actually think that that’s the story full-stop for generations. And you know now in my 40s as the Radio National breakfast host I can probably have a lot more sort of social power than I’ve ever had but still when you talk about scrutiny I feel like anything I do is surveilled in a way that I don’t think exists for everyone.

And I think there is a strong gender lens on it and the lens of you’re different, I’m going to surveil you and I think all journalists can do is be really good journalists and tell the stories fiercely and proudly of all Australians as much as you can and fairly and try to – kind of try and cut out that noise and try and do your job the best you can and that will carry you through. And I think that women have become better at supporting each other. I also think that when I was starting you know that feeling of being – there can only be one winner who’s a woman in this room and so who’s that going to be? And you know I’ve got older sisters who have always been my mentors and I remember at high school, I went to a co-ed school, my sister said to me once – this is really a definitive moment in my life, I go on about it and she’s always like you’re always going on about this thing. She noticed ‘cause I was really competitive at school, that I often competed with the girls – I didn’t really think about the boys very much and that’s because I always just thought that they were entitled to everything and you know being the best and she said why is it that that’s the prism, you know?

And ever since I broke that prism at a very young age and started thinking about supporting other women, they’re not a threat to me. On the contrary, the more of us there are the better our workplaces have become, I think there’s been a real shift in my experience as a journalist on the issues we cover ‘cause it’s not just about our experience and I think that’s a really fertile ground, it’s about the sort of stories that we cover. I think about the issues like stories around domestic violence that I would never have felt like we could cover at the newspaper I worked at 20 years ago that have now become the sorts of stories we should and do cover and the way we will give them prominence on a program like mine in prime time that that wouldn’t have happened. And that’s because it’s the advocacy of women saying these are stories and pushing against often male gatekeepers who have told us that they weren’t stories. So we’ve also changed the news agenda, I think.

A: Absolutely. When I was a crime reporter we had a police scanner and you’d hear the codes and you’d be proficient in what each code would say and I would go oh there’s a 402 or whatever and my editor would go oh it’s just a domestic, just a domestic. And then we had a very, very, very loud fight in the middle of the newsroom over how there had been 18 just domestics over that Friday night and perhaps there was an issue in the town that we were living in that as the local paper it was our duty to cover. And it was the first time that he had really considered that maybe domestic violence is something that people would want to know more about that was happening. It wasn’t just from the 6:00 swill that you just you know shut the door on and let go on but it literally took a like screaming match in the middle of a newsroom where I was like enough to kind of bring that change so I can see that.

But then to what Murph was talking about with the year that we had leading up into last election I found it really interesting that a lot of the people who were leading that discussion, and it was women journalists like you two who were you know and Laura Tingle and Louise Milligan and Karen Middleton who were really pushing this as an issue, and Samantha Maiden, of course. You were all labelled activist journalists and then I have never seen any of our male colleagues labelled as activist journalists when they’re talking about issues that are close to their experiences. I mean Nick McKenzie is an amazing reporter, he’s never been labelled an activist journalist and then you have other equally amazing reporters who were women and suddenly oh they’re talking about lady issues so they’re activist journalists. So what was your take on that?

K: I think just listening to my colleagues and friends here, I think there’s a couple of things and you know the sort of – the accidental activist is a funny – it’s sort of a funny career cul-de-sac but anyway putting that to one side I think there’s the sorts of let’s just call it you know the gender gap that these two have narrated very vividly in terms of perceptions in a newsroom or culture in a newsroom. But I also think something that’s not sort of a – not quite so binary, it’s a bit different. Basically - and I did write about this actually in a chapter that I contributed to Julia Gillard’s edited book on the 10 years, 10-year anniversary of the Misogyny Speech – I think in terms of journalism, certainly for journalists of my generation, you are trained to narrate objectively in a neutral voice. That is fundamental to the idea of what a journalist does, we bear witness and we narrate in a neutral objective voice. Nobody stands at the top of the newsroom and says don’t write like a woman, no one says that but nonetheless you are hewn in this culture where that is the expectation.

And of course because you know the primary trailblazers in our profession you know or the people who know how to find their light, Mr DeMille, are men of course that then sets the standard for what an objective neutral voice is. The objective neutral voice of journalism is a male voice, it’s not a female voice and so you can spend a lot of years as certainly I did honing that voice, cancelling your own voice in order to better perfect the fundamentals of your profession which is not how you feel about things, it’s what you’ve witnessed. But the fact is we do perceive things differently sometimes. So how do you achieve that voice? And my own journey over that last 12 months of activism was I woke up one day literally and I thought being a woman is actually relevant, it’s relevant. I’ve got something to contribute because I understand these dynamics.

But that involves shedding an enormous amount of conditioning in order to get yourself to that point and like I said you know my experiences have been largely benevolent and like I said no dictator, male dictator said don’t you dare write like a woman or describe something as a domestic, oh my god. No, fortunately not. But it’s just – and that sort of loops me back to Amy’s fundamental question which is why were we activists? Well because we were writing differently, we were perceiving differently, we were recording events differently and that was at the root of the discomfort. It wasn’t so much that people thought you know - it wasn’t so much activism, it was a departure from norm and obviously you know a discomforting one for some colleagues.

So you know is that activism? Well yeah, yeah, it’s probably radical activism, actually, just to say there is a journalistic voice. I’ve spent my entire career trying to perfect it but at various times I will assert my own voice and is that activism? I don’t know, you guys might have some thoughts about that. You know I certainly don’t shy away from the term because as I said you know it was an act of activism, really, to say I’m a woman, I understand this. That perspective might be relevant. But yeah, it was very interesting just to see sort of you know have that external you know it was sort of like your practice was being narrated in real time, it was really very interesting. So anyway is it activism? Probably. Does that matter? No.

A: Well I’ve seen men get very, very emotional over industrial relations policy so you know just proving they’re too emotional for politics, obviously. I will say though that having you as my boss has freed me in a way to use my voice that I haven’t been able to use in other newsrooms and it’s not because you’re saying you’re a woman you know write how you want, it’s because you take me seriously when I say this is an issue I am upset about or I am activated on or exercised over and you listen to what I’m saying rather than just patting me on the head and saying oh well you know off you go, little emotional girl you know maybe you’ve got your period which has been said to me by a male editor. So – but you don’t and you provide that space and obviously you do it for our male colleagues as well but I think they’re used to being listened to whereas I think you know the women who work under you aren’t necessarily used to being listened to and then being guided in a way to take that interest and that you know rage or whatever it is and putting it through that journalistic lens in a way that you are able to tell other people that story. That’s been a key, key difference I am so grateful for.

And when I read Patricia’s book and I think about you know some of these women who were dressing as men in order to be able to go in and report on things or changing their voice completely, starting off on soapboxes and ending up being you know somewhere on the right side of Pauline Hansen in order to be able to fit in and to rise up in their newsrooms, I just think like that is the key change, having more women in positions of power has allowed other women the space to use their voice. So I just wanted to say thank you to Patricia and to PK and to Murph for providing everyone below you who’ve come after you that space because I think it is changing the Australian conversation, very slowly we’re starting to see those changes.

But then we do also go back two steps because Patricia, you interview in your voice which if you read those questions, they are no different to what you would hear male colleagues. You do find nuances, I think, that our male colleagues don’t. You are an intense listener and you find the gaps in what people in power are saying and it’s an amazing skill but you do get a lot of blowback for asking those questions and I think it’s something that everybody with a higher voice finds, that no matter who you’re interviewing or how you’re doing it, you’re accused of interrupting, you’re accused of being shrill, you’re accused of talking over someone. Do you think it’s just because we’re not used to hearing women voices asking those questions?

P: Yeah, I do and yeah, I get some really, really awful text messages, actually, a lot of really negative commentary. I get lots of positive too, I’m not here to cry – well you know make you feel sorry for me but I’m just reflecting on what some people hear, I hear, yeah, you’re aggressive a lot. And I’m like this is just how I talk, this is how we talk in my ethnic family. It’s actually the way I talk for real like – and you know like that sort of –

K: If they’re worried about that, they should see her in Maker’s Christmas.

P: Well it’s a bit like that because I think that we – and I do think that intersectional story’s an important one because I think if you’ve only heard a sort of very particular kind of privileged private school voice mine probably does – I’ve been told a few times and I’ve got to tell her this, that you just sound like Jacqui Lambie. Yeah and it’s meant as a slur, yeah? But really what that’s saying –

K: I would take that as a compliment, myself.

P: Yeah but it’s meant as a slur –

K: I know, I understand.

P: - I’m saying something different which is it’s a class-based comment and I know it and for – in my early part of my life I did think should I try and adjust this about me? Should I try and sound different? Should I emulate my Anglo-Saxon colleagues or should I try? And I’ve made a decision that firstly I can’t ‘cause I’m a terrible actor, that’s actually the truth. I can only act in the part of myself ever but also I don’t think that’s what Australia – where Australia is at. So journalism, back to the way our newsrooms and women are shaping them, journalism has actually got a big issue with meeting Australia just like politics does and Australia – they’re used to wogans like me, they live among them. It’s just cool. There’s a certain part of Australia that probably is more resistant and that part of Australia needs to catch up a little with the rest of the country ‘cause it’s actually a really different and diverse country and so the stories that we’re telling need to be more diverse as well.

The way that we narrate the stories, we need to understand that people with different perspectives need to be platformed. And yeah, back to the way people hear things, I do think there’s a real gendered lens, I mean it’s a fact. But you know my predecessor is a good friend of mine, Fran Kelly, she was on air for 17 years, she faced constant sexist abuse about the way that she also interrupted so unfortunately it’s just part of the job. I hope with time people will – this will be more normalised and that you know uppity women like me will just be seen as just journalists doing their job like I’m actually paid to ask hard questions of politicians. If they came and I just massaged them every time it would be a little bit concerning for the taxpayer to be paying for that so it’s actually my job description. If people find it challenging to listen to I think that says more about them and maybe changing their own ideas about what we think is normal because – yeah, it’s actually – it’s normal to have a robust discourse. It has to be respectful but I don’t think I’m very often disrespectful to my guests.

A: Murph, what damage do you think was done – I mean and obviously it was part of the society but that women were corralled to talk about you know women’s issues and so they had the women’s pages as Patricia writes about in her book and trying to move those women’s pages into something more relevant you know has ended as she reports you know with women losing their jobs, losing everything or just you know quietly going along with it because that’s the way that they could survive in that newsroom. What damage do you think that has done to the Australian media psyche and as part of that like do you think a Prime Minister will ever call on a woman journalist first other than when they’re making a point?

K: Oh dear. Yes, on the last question oh I don’t know, that’s a utopia we can all work towards, right?

A: Phil, Chris, Andrew, Mark.

K: But it’s often – it is often – I mean there is that sort of you know like likes like, right? There is that but they also – I mean look, Patricia has a beautiful sonorous broadcast voice, I have a very thin reedy voice and I have difficulty screaming in press conferences so part of it is the broadcast cadre which is often heavily male, particularly in television, can actually project their voices much more than some of us, me. Anyway setting that to one side – Amy, love, what was the other bit of the question?

A: The damage –

K: Damage, no, no, no, thank you, thank you for cueing that because I want to pay tribute to one of my most important journalistic mentors which is Michelle Grattan. I worked with Michelle first at The Financial Review when I was you know 25, we were very fortunate to have her briefly after she left The Canberra Times and before she went back to The Age. She just wrote a couple of columns a week for The Fin Review so by Michelle’s standards she had a very light workload which was brilliant for me because I sat directly opposite her and I took the opportunity to lock on and decant that brain for all it was worth and then later I worked for her, I worked with Patricia for a while at The Aus and then I worked – I came back to The Age and worked as her deputy for quite a period of time. Now why have I raised Michelle? Because Michelle’s first journalistic job was the women’s page. When she was you know she was like a politics academic, she was on an academic path. I think when she first started working for The Age she was sort of on the women’s area because that’s what women did, right?

And Michelle I think took the view that the women’s page would be a transient stop in her journey which was enormously beneficial for all of us because she did the women’s page and then got herself out of the women’s page as fast as humanly possible and then landed in Canberra as a political journalist as befitted her training as a political scientist. And so it’s sort of like she somehow managed to reverse out of the cul-de-sac by force of will and personality and anybody who knows Michelle knows in her quiet, unassuming, modest, humble way how implacable Michelle is on the path of anything. So we in Canberra are extraordinarily fortunate, me in particular for how much time she gave me at very critical points in our careers.

Now I don’t know you know because obviously there would have been women who were unable, who just weren’t quite as implacable, I guess, and ended up doing that or a version of that for much of their careers but we’re very fortunate that some women basically were the breakthrough generation, she certainly was in terms of political journalism, also Anne Summers, a very important breakthrough role model for women of my generation. They were sort of the very early Canberra bureau chiefs so that by the time I arrived I could look around – there weren’t many of them but they were there, we knew they were there, we knew there was a valid career path and you know Michelle – one of the most important lessons Michelle taught me was you don’t have to be in a hurry, you just have to be good and you have to be right. And they are – I cannot place a value on that as just a plum line in you know in terms of career development.

So while we’re giving a shout out to the wonderful women who have helped us it would be very remiss of me and us not to pay enormous tribute to I think the most significant political journalistic figure you know – obviously she was in a golden generation which included brilliant people like Laurie Oakes and all of that sort of stuff but you know Michelle is a beacon. And I remain always frustrated because when I’m in events with Michelle she always asks a better question than me and I wonder how long I’m going to have to work in order to come up with a better question than Michelle. So anyway I just wanted to share that with you guys and with her. She of course will be filing and not listening but Cobber, thank you.

A: Absolutely. When I’m in Parliament too to run The Guardian live blog I get there before 7 and you know it’s kind of a race to get past Michelle. And she is always there last as well so she is an absolute just legend and I think that everyone, everyone who is in that place owes her a great debt of gratitude. And you know Cobber will always just like pop her head out and just sort of say so what’s going on? Just like hi Michelle, yeah, what’s going on? So it’s good to know that that curiosity never goes away either.

But on that, on like legends like Michelle and you two wonderful women like PK, what is the most important thing women can now do to help other women through the door?

P: I believe in actively helping those who you see emerging which I do all the time in the ABC so you know actually not only being good at what you do but being generous with your time and time is you know we’re in a rush and I think that resonates with me, the – be good and don’t be in a rush and get it right is really important. But also understand that I think when you get to a certain part of your career that you are – you, you know, it is actually your job and obligation to leave this profession better, particularly because it’s such an important profession, I really believe, in shining light on things that we need that light shone on in our community but to actually make sure that it’s in better shape when you leave it.

So I’ve always you know everyone knows this in my own direct team but you know I want the next you know RN Breakfast host to be you know – well they’ll choose, I’ll be careful but I want all of those young women who are coming through not to feel that reluctance that perhaps I felt at a young age but to feel like they can push through and to know that they can be supported and can be in really safe workplaces too because that’s the other part of the story. My workplace wasn’t always, didn’t always feel safe, I always had to navigate things that I don’t think I should have so I think the best thing you can do is to be generous with your time and understand that you actually have something to share and doing that is actually providing something really important in the future of the profession.

And I don’t know if all always do that naturally but I’ve started becoming a lot more aware that that’s an important thing to do because I think particularly young people and young women are desperate for that mentorship. And when I provide any of it the sort of enthusiasm I get is so overwhelming like it’s not just ‘cause I’m giving it, you get something out of it too, it’s a loop, yeah? It’s so overwhelming that they’re like wow and they want to know how did you get to where you were? And of course you know oh you tell them your war stories but it’s a bigger story which is I don’t want to be – I’m going to say this – I didn’t – I had some women who didn’t support me and weren’t very nice to me and men, and men, not targeting women. But I don’t ever want to be – and this is really important – I remember once hearing some woman say when there was an argument for more childcare, I didn’t get childcare and I raised my kids.

I never want to be like that. I don’t want to say oh no one really helped me ‘cause sometimes I didn’t get much help, particularly in the early part of my career so I’m not going to give that to someone else because that was wrong that’s - wasn’t the right way to actually have a healthy workplace. And so that’s the big thing for me, not going I didn’t get it so you shouldn’t get it either but to actually say I didn’t get it, it was detrimental, I could have been flying a lot earlier and so let’s get you flying earlier ‘cause it’s good for our democracy too as well as for you as an individual so providing that, paying that back.

A: Absolutely and another reason having you know a Murph in your corner, Murph not only you know held my child a couple of hours after he was born, she’s also you know basically got me water and things and fed me while he strapped to me and I’m blogging and given me you know as much time off and flexibility as necessary, not something that you know a lot of women were granted like even in five or so years ago. It’s just all of these tiny changes where you go wow, that was really hard. It doesn’t actually have to be that hard, here’s some flexibility and you know – you know I’m working because I’m positing every five minutes so it’s not like I’m you know slacking off but you put that trust in me because you know what it’s like and you know what it’s like. So those are the changes I think that having you know more women in not just telling you the news but in charge of people who are helping to tell you the news.

P: There were positive women in my life. One of them was Katherine Murphy and when I came back from maternity leave and I was a bit of a hot mess myself she said to me – I remember, you probably don’t remember ‘cause you do this all the time and you grabbed me once ‘cause we work in the same newsroom and she said you can pause and enjoy the child as well as the job. Because what she rightly identified is that I was feeling under so much professional pressure not to let having a child steal my career that I wasn’t sometimes enjoying what was happening which was that I’d just given birth to a live person. And it really did – and Jenny Macklin was another person, former Minister obviously, who gave me some very good advice about enjoying both because actually we are our best selves when all of those parts of us are functioning well rather than seeing them as competition with each other and that’s good leadership, understanding that actually our best workers are people who can enjoy all those different parts of their lives.

A: Absolutely so we’ll open up to a couple of questions now if you want to direct it to one of these lovely women. We’ve got some microphones? Yeah.

Au: Can you hear me?

A: I can, yeah. I think for the recording it helps with the microphone.

Au: So coincidentally Judy Woodriff, PBS News Hour, also announced her retirement after five decades of political journalism coming to the end of the year and she tells stories very similar to those that the three of you have been telling. Imagine coming of age as a political journalist in the early ‘70s in the US and fortunately her first peak was this unknown Georgia politician named Jimmy Carter. And it was only courtesy of that complete coincidence that she then moved through the amazing career that she’s had. My question is this, her interviewing style is quite different from I would say a prevailing interviewing style in Australia and I don’t want to gender this but – and obviously there’s big national differences but the way she comes at an interview is less like Kerry O’Brien and Barry Cassidy for example and is much more that amazingly intense listening mode.

And so she gets something different from what the other style gets out of people and there are pluses and minuses about it. The one thing that – where her gender comes through, though, is she’d be as really straight but her face, the emotions that fly through the face as she is listening tells you all you need to know about where she’s at with her – the person she’s interviewing. Anyway I guess the question is what interviewing styles are being channelled historically today? Do we go back to Kerry O’Brien and Barry Cassidy or earlier and what are the ups and downs of having to navigate that kind of interviewing style yourselves?

A: Such a great question because –

K: I suspect Patricia and I are going to have slightly different perspectives on this.

A: We’ve got slightly different interviewing styles too.

K: Well just – yeah, thank you for the question but Patricia is a broadcast you know legend who needs to take the question first. No, that was me, that’s respect, that’s respect. No, it is, it is.

P: Well –

K: No, I’ll do it first if you want.

P: Yeah, you go first.

K: Alright, okay, okay.

P: But thank you for the respect.

K: I was respecting my colleague. No, look, if you guys listen to my podcast and you listen to Patricia, how she interviews on RN, they are very different styles. The main reason they’re different styles is because I am not a broadcast journalist, I’ve not been trained as a broadcast journalist and frankly I have no interest in becoming one. So I basically interview on the podcast the way I do for print and digital and the listeners just come into that conversation with me so it’s a much more – relaxed is a stupid word because you do so much preparation but it’s sort of like I just want a conversation whereas Patricia is you know is a relentless news hound, thank god –

P: Someone’s got to get the news.

K For all of us –

A: Setting the agenda.

K: - who sets the day up every single day by throwing multiple news lines every program which then we develop over the course of the day, that’s what I’m talking about with respect. But I don’t – I do not interview that way. Often we will get a story on the podcast just because it’s an interesting conversation with interesting people who make the news so sometimes even despite my best efforts we actually emerge with a story. But it’s sort of –

A: She’s being very humble, I’ve seen her prepare for this podcast, it’s like a week of intense reading of everything this person has ever said.

K: No but it is a different style but see I mean I would never host RN Breakfast, one, because I couldn’t do it, I would be hopeless at it and it’s just not a conversation that I want to do in that format whereas thank god Patricia wants to do the conversations she does every day with multiple newsmakers in that format because it’s so beneficial for the rest of us.

P: Yeah, I mean I think – I’ve been a print journalist as well, I’ve actually been on – I’ve done all of the platforms and I personally think it benefits me as a broadcast journalist. And as a print journalist you will have – you’ll try and draw out – and it’s a whole different kind of skill, right? But when I’m on air and it’s 7:32 or whatever and I’ve got the main interview in the morning with – insert newsmaker, the Attorney General this morning, Mark Dreyfus – I’ve got – there’s all these other restraints that are perhaps boring but I’ll share it with you like I’ve got 10 minutes on the clock and I’ve got a range – I’ve always got more questions than I can possibly ask and I don’t want to go through a list of questions, I also want to actively listen and follow the conversation. So if they something I didn’t expect or is surprising I can follow that – why are you doing that? When did that come about? Rather than going through my list of questions.

So each interview is not so formulaic as you’d think, it is based on how that person responds and sometimes they will give you brief answers that will be – you’re moving it quickly and you can talk about lots of different things, other times you’ll draw someone out differently.

And in terms of where you learn your style, that question you asked you know and you mentioned two men whereas I’ve listened to lots of women where I’ve probably you know Fran Kelly, Leigh Sales, there are lots of women that I’ve probably more watched than the men, myself and all of those things I think you pick up like you do with all your journalism, by reading and watching other people write a news story. All of that is learnt but at some point you develop your own style and it’s not even I’m going to develop my own style today, it happens naturally if you allow yourself to fly and so I don’t think I interview like any of those people entirely, I interview like me. And there’s a bit of everything in there because I’ve been an active listener of current affairs my entire life so at some point I’ve probably picked up some things about how you ask questions.

But at the end of the day, and Barry Cassidy taught me this, actually, there you go, Barry ‘cause I’m buddies with Barry and Barry once said sometimes the easiest and the best questions to ask is someone answers it and you go but why? And it’s very simple but actually why? Why are you saying that? What’s motivating that? They’re often the best questions rather than something precooked where you’ve come up with almost the answer in the question.

A: And I cannot hide my facial expressions or what I’m thinking and so I tend to just let my face do the talking for me and I get into a lot of trouble for that ‘cause somebody’ll be saying something and I’ll be like what?

K: Amy’s being ridiculously –

A: I am not, there are many photos Mike Bowers has of me going –

K: No, I’m just going to call that out as Amy is a formidable broadcaster, having had that training, as well as a digital operator so let’s just get real, sister, please.

A: Other questions?

K: Oh come on, yes.

A: Someone at the front and then you, sir? Well just down here.

Au: Thank you very much for the talk this evening, it’s been fabulous. Just a comment to start with. You mentioned your interview with Mark Dreyfus this morning. I thought your interview with Noel Pearson was spectacular –

P: That’s ‘cause you thought Noel Pearson was spectacular.

K: No, it was a very good interview.

A: You gave him the space –

Au: You give him the opportunity to say those most beautiful things, it was fabulous. And Katherine, I just wanted to say to you too, the way that you always push back on climate change gives me hope. You really push people to say I’m sorry but you’re contradicting what you did six months ago or five years ago and that long-term memory is so important. But I suppose you’re talking about to – and my question is to you, Amy, about sort of always trying to think about how you can help women and I suppose one of the greatest things that I heard you say – it reminded me of that sentiment that all you have for – was it evil to occur in the world? Is for good men to do nothing. Is that sort of sentiment what led you to coin the phrase crumb maidens which is fantastic.

A: Crumb maidens kind of came out, just conversation with friends when I was very frustrated at seeing people act against their own interests and uphold power structures because they were just hoping for some of the crumbs of that power and it’s something that I think that everyone can recognise and I am not alone in coming up with the term. I’ve since learnt that there have been a couple of other people who had also coined the term. I guess it’s because the crumbs of power is you know a pretty easy analogy to grab for.

But I think – this is probably a little bit off-topic but I don’t necessarily think that sharing a gender or sharing an intersectionality with somebody immediately makes them your ally. People are different and have different views about things and no one group is a monolith so no women are going to think you know – women aren’t a monolith, they aren’t always going to think exactly the same. But it drives me insane when you see people actively contradict or hide somebody else’s experience so we’ve had politicians such as Julia Banks come out and say this was my experience within the Liberal Party and then you had a long line of Liberal Party women MPs come out and say I’ve never seen anything like that, that has not been my experience. Well great for you but it is somebody else’s experience and they’ve come out and they’ve spoken on that. So either like shh, just let them you know have the space and say nothing or listen to what they’re saying ‘cause wonderful that you haven’t had that experience, that you’ve never experienced sexism in politics, great, you’re a unicorn, fabulous for you –

P: Happy days.

A: Yeah, I know, wow. But when other people are saying this has happened to me it is your job to listen and that’s kind of where – and it wasn’t just for politics, it applies to anything. If anyone is actively upholding a power structure hoping you know – it’s also called a pick me like pick me, I’m – like I’m your friend, pick me first. If you were actively contradicting or standing in the way of somebody else explaining their experience then to me like I don’t need to hear from you ‘cause I know exactly what you’re doing. And I thought during that moment that Murph has referenced, that was something that needed to be called out and perhaps that is another thing that comes from being a woman in this industry, when you notice people actively acting against their own interests and their own interests of other people who share those experiences so –

M: I’m afraid we’ve run out of time ‘cause I suspect we could converse for quite a while longer, really, so it’s been interesting listening to you speak. I stand here as the third female Director General of the Library – long line of blokes before that but of course I work in a really female-dominated industry so it’s always fascinating to hear about experiences you know in a very different industry where their situations are quite different. Mind you, I think our profession is devalued because we are primarily women. That’s a tale for another day. Don’t get me on that soapbox.

But look, I think we’ve had a wonderful conversation tonight, we’ve heard from these three wonderful women about the respect that they have for those who’ve gone before them and those who are actually still actively in the space but have kind of given them the space, the nourishment and the encouragement to move forward. It perhaps makes it even more astonishing then to think of the women that Pat wrote about who often were not in that kind of environment but were very much on their own as indeed Pat herself was.

So if you haven’t yet had a chance to purchase a copy of this terrific book, and I told Pat just beforehand that I had my copy on my side of bed and it has moved to the other side of the bed and it’s not been relinquished by that reader so I’ll get it back eventually. It’s a terrific book, you’re going to find about these people that you didn’t know about. As I said before Pat has singlehandedly rescued so many women from obscurity who deserve to be remembered and I’m really proud that we as the Library were able to be part of that story in publishing Pat’s book.

So the bookshop is open right now, ready to welcome you if you too need to buy a copy or a second copy as I may need to. And Patricia has kindly taken the time to sign some copies for us so please do come up, buy a copy of the book at a discount tonight at the bookshop and just take the opportunity again to thank these wonderful women, thank Pat, thank Amy, Patricia and Katherine and thanks to all of you for coming out tonight. I don’t think we’ve had this many people in the theatre since before that thing started happening and we hope to see you back at the Library very soon so have a lovely evening.

Applause

End of recording

Join us for the launch of NLA Publishing's new book, Bold Types: How Australia's First Women Journalists Blazed a Trail. Listen to a panel discussion featuring Amy Remeikis, Patricia Karvelas and Katharine Murphy as they talk about the history of Australian women journalists and reflect on their own experiences and careers.

Bold Types tells the story of women journalists in Australia covering the period from 1860 to the end of World War II.

Tracing the journey of more than 13 independent, adventurous women who ventured far and wide and fought for relevance and gender equality, together these stories illustrate the gains and setbacks of women journalists over nearly a century. In each successive story, their tenacious determination and courage shines through.

Bold Types author Patricia Clarke was a trailblazer herself, as the only woman on the Melbourne staff at the Australian News and Information Bureau in the early 1950s.

The book was launched by Amy Remeikis, political reporter for The Guardian Australia, who wrote the introduction for Bold Types.

Bold Types is a book that will resound with and inspire readers, in a world where women are still fighting against workplace discrimination, gender-based violence and for sexual and reproductive rights.

About Patricia Clarke

Dr Patricia Clarke is a writer, historian, editor and former journalist, who has written extensively on women in Australian history and the history of journalism. In 2001, she was awarded the Medal of the Order of Australia for services to Australian history, and she is an honorary fellow of the Australian Academy of Humanities. Bold Types is her fifteenth book.

About Amy Remeikis

Amy Remeikis is the political reporter for The Guardian Australia. She writes on major political issues in Australia, crime, the courts and the environment. She is a regular panellist on the ABC's Insiders program and was the inaugural nominee for the Young Walkley awards.

About Patricia Karvelas

Patricia Karvelas is a prominent and highly respected award-winning Australian journalist, television and radio host, podcaster, political journalist, and commentator. She currently presents Radio National’s (RN) flagship radio current affairs program RN Drive. In 2019, Patricia began anchoring a daily program on ABC News TV called Afternoon Briefing. Patricia has also worked in several senior roles in print media, working for The Australian newspaper where she was the paper’s political correspondent in the Canberra press gallery.

About Katharine Murphy

Katharine Murphy has worked in the Parliamentary Press Gallery since 1996. She is currently political editor and Canberra bureau chief of The Guardian Australia, and the host of the Australian Politics podcast. Katharine is a two time winner of the Paul Lyneham Award for Excellence in Press Gallery Journalism and a Walkley Award for political commentary. She has an honorary doctorate from the University of Canberra. She is the author of On Disruption and two Quarterly Essays, The End of Certainty: Scott Morrison and Pandemic Politics and Lone Wolf: Albanese and the New Politics.