If Australians were to pick a national symbol the kangaroo would surely be it.

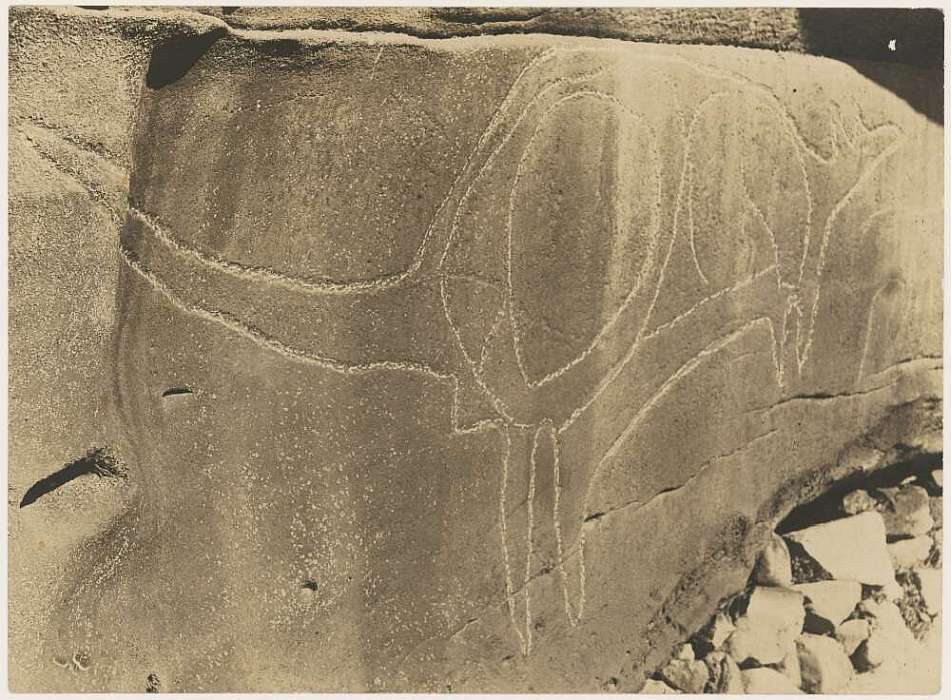

Indigenous Australians have had the kangaroo as a totem, a source of food, furs, tools and ornaments, and as a subject of rock art for tens of thousands of years.

Aboriginal rock carving of a kangaroo with internal circular patterns at Burraneer Point, Point Hacking, NSW, 1923. nla.cat-vn6105193

When Europeans first encountered this strange creature it typified the exotic nature of a newly found far away land and became an enduring part of the natural and national representation of this island continent.

The kangaroo was so different to anything seen by Europeans before that at first it could only be described by clumsy comparison to other more familiar animals. The Library's collection has many such first descriptions of this and other animals, such as the explorers' journals and published accounts of the voyages. We also hold 18th and 19th Century encyclopedias on nature that were very popular among Europeans who wanted to learn about these new species and encounters.

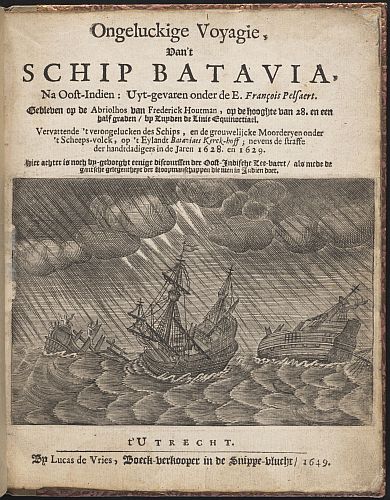

The first recorded European sighting of an Australian marsupial was of the Tammar Wallaby in 1629. Dutchman Francisco Pelsaert, captain of the ill-fated Batavia wrecked off the coast of Western Australia, described in his journal seeing a strange animal like a type of cat. But as the rest of his story involved mutiny, murder and an epic rescue, mention of this small unnamed creature gained no attention.

Francisco Pelsaert, title page from Ongeluckige voyagie van't schip Batavia na Oost-Indien uyt-gevaren onder de E. François Pelsaert, 1649. nla.cat-vn5350559

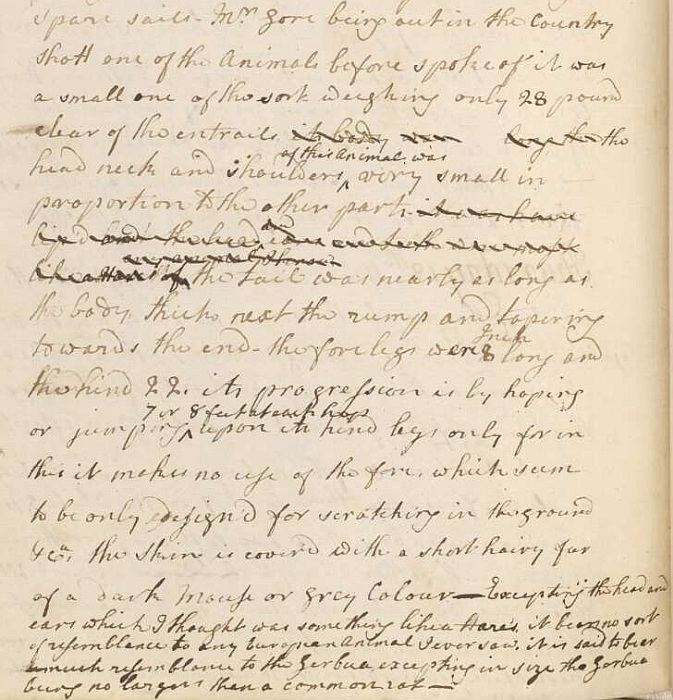

It was the Endeavour voyage under James Cook that provided the first written European encounter with a kangaroo species, which was sighted while repairing the ship at what is now Cooktown in June and July 1770. Cook wrote in his journal "it bears no sort of resemblance to any European animal I ever saw", but it had the colour of a mouse, was the size of a greyhound, looked like a jerboa, and moved like a hare.

James Cook, entry for 14 July 1770 in Journal of H.M.S Endeavour 1768-1771. nla.cat-vn3525402

Transcript available at http://southseas.nla.gov.au/journals/cook/17700714.html

Being the ship's lead naturalist, Joseph Banks was also intrigued by this new animal. But in his own journal he went further, noting that it tasted good as they ate a specimen that had been shot and studied.

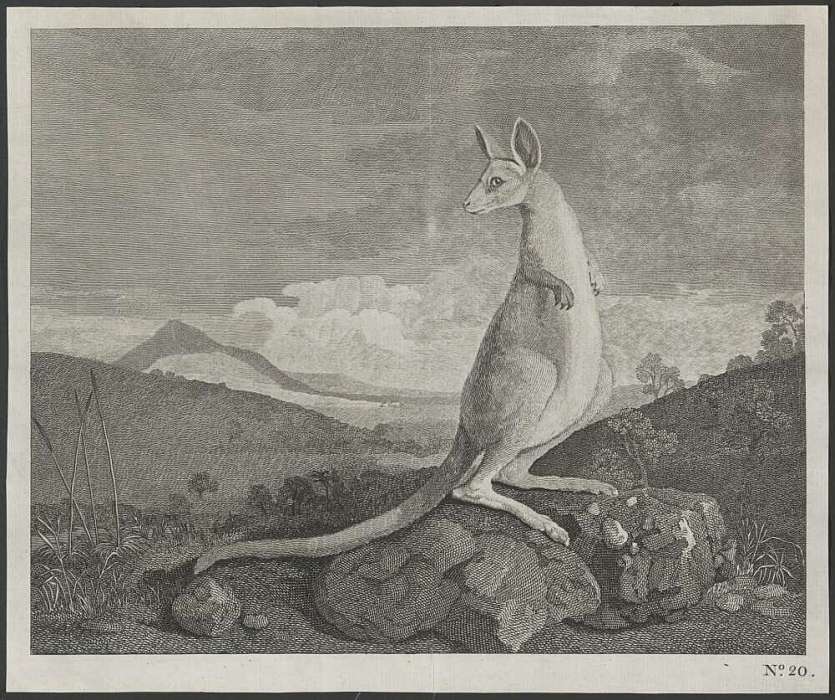

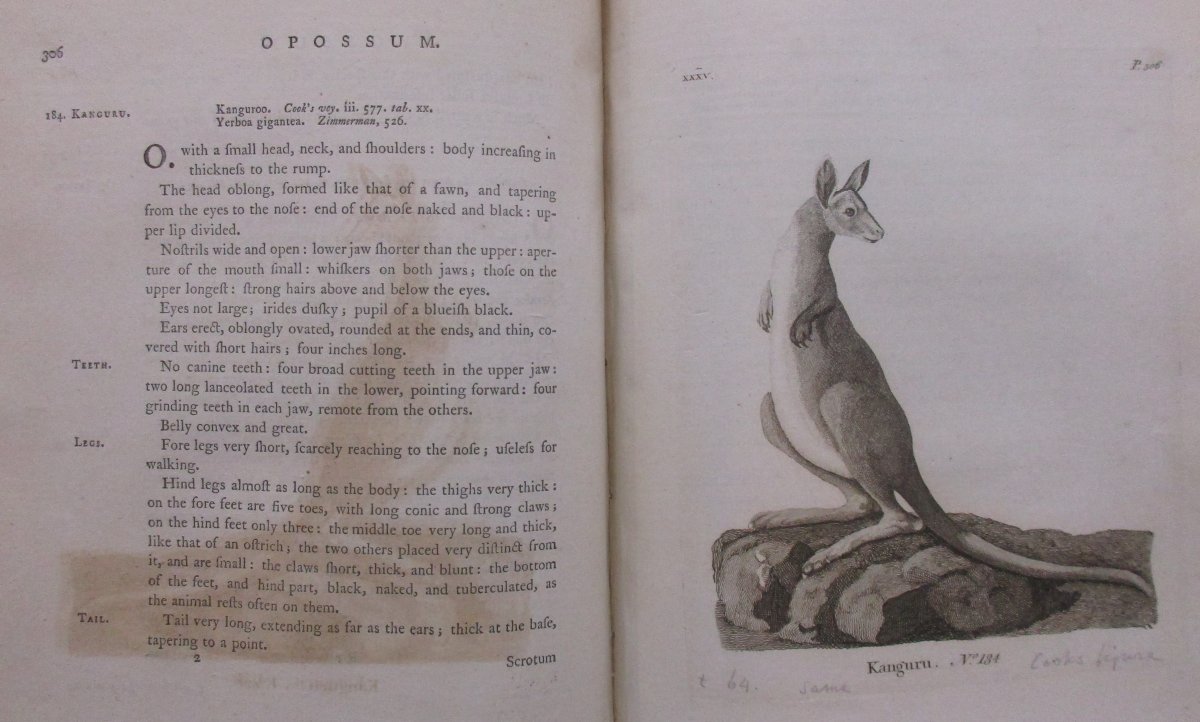

The Endeavour artist Sydney Parkinson died on the voyage after doing only a few quick sketches of the kangaroo. When the expedition returned to England George Stubbs, best known for painting horses, studied the descriptions of the kangaroo by Cook and Banks and the skinned specimens they collected. His resulting artwork of the kangaroo was included in the published account of Cook's voyage in 1773. With this first appearance in print the European public was mesmerised by this strange creature.

George Stubbs, An animal found on the coast of New Holland called kanguroo, 1773. nla.cat-vn2651211

Banks gave this animal the name "kangooroo" from the word gangurra, which is what the Guugu Yimithirr peoples of North Queensland called it. But this is just one of some 250 Indigenous languages that were spoken at the time, so different language groups had different names for this same animal. When the First Fleeters arrived in 1788 they had Indigenous word lists produced by Banks, but were confused to find the word kangaroo was not used by the Eora peoples of the Sydney region. They had a completely different name for the animal - patagorang.

It proved difficult to fit the kangaroo into the animal kingdom as then understood by Europeans. From the first reports of Cook and Banks the kangaroo was considered a giant rodent. In one of the first popular publications to describe the kangaroo in 1775, A modern system of natural history: containing descriptions, and faithful histories, of animals, vegetables, and minerals, Samuel Ward lists the new animal under jerboa. However he seems to realise this is not a perfect fit:

"Mr Banks brought home the skin of an animal, which he calls the kanguroo, which, from its general outline, and most striking peculiarity of its figure, greatly resembles the jerboa, yet it entirely differs in size, and in many of those minute distinctions which point to the general ranks of nature"

In 1777, to conform to the structured classification of the Linnaeus System of Nature, German zoologist Eberhard Zimmerman named the new animal Jerboa gigantean - the large jerboa. Welsh naturalist Thomas Pennant then placed the kangaroo in the same genus as American opossums as Didelphis gigantean, although even then he called it a "very anomalous animal".

Thomas Pennant, History of the quadrupeds vol. 2, 1781. nla.cat-vn995252

But French naturalist Georges Buffon was not convinced, believing the depiction of the kangaroo to be "defective", by which he possibly meant unbelievable, and he did not at the time include it in his massive encyclopedic Historie naturelle.

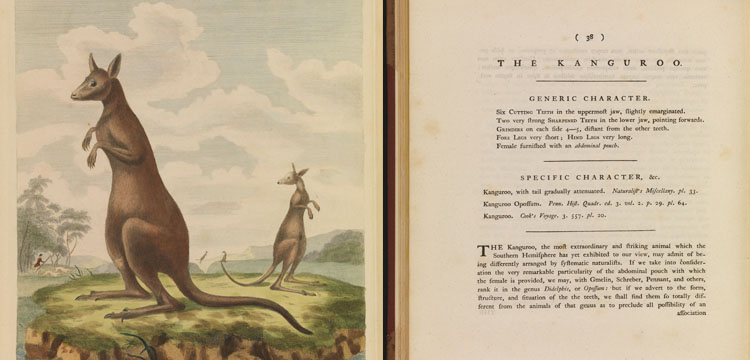

In 1796, George Shaw addressed the emerging confusion on how to classify the kangaroo in Museum Leverianum:

"The Kanguroo, the most extraordinary and striking animal which the Southern Hemisphere has yet exhibited to our view, may admit of being differently arranged by systematic naturalists."

By then more specimens had been found, descibed and studied and it became clear to some that kangaroos, wallabies and others were too unique and extensive to be lumped in with other animals.

Shaw believed these animals had too significant a difference to both the jerboa and the opossum and felt "we need not have the slightest hesitation in forming for the Kanguroo a distinct genus". He renamed the Grey Kangaroo to Macropus giganteus and a new taxonomic genus of animals was created - the Macropods - meaning great foot.

George Shaw, Musei Leveriani explicatio/Museum Leverianum vol. 2, 1796. nla.cat-vn488821

When ornithologist John Gould arrived in Australia in 1838 he predictably intended to focus on the bird life, but having "found myself surrounded by objects as strange as if I had been transported to another planet" he broadened his studies to other animals.

One entire volume of his The mammals of Australia finally published in 1863 was devoted to kangaroos and wallabies. With 14 new such species described for the first time, this became the most thorough scientific classification and artistic depiction of macropods to date. It is still seen as one of the finest European studies of Australian fauna, and one of the most visually stunning.

H.C. Richter, Macropus ocydromus, West Australian Great Kangaroo from John Gould, The mammals of Australia vol. 2, 1863. nla.cat-vn760101

Confusion about just what to make of the kangaroo from European society at large is perhaps well illustrated by a small print from 1858 by French satirist and artist Honoré Daumier titled A scientist trying to befriend his son with a great kangaroo from Central America.

In it a fearsome but slightly comical looking wild kangaroo menaces a terrified looking child, but why would Daumier think kangaroos came from Central America?

Honoré Daumier, Savant, essyant de lier d'amitié, son fils avec le grand kangourou de l'Amérique centrale, 1858. nla.cat-vn5497466

The case of mistaken identity could be down to the continuing lack of an accepted way to classify the kangaroo, even well into the 19th Century. Following Shaw, a series of British naturalists placed the kangaroo and its close Australian relatives in the new grouping of macropods. But continental European scientists continued to treat it as closer to American marsupials, still trying to categorise it with animals they already knew. It took time for these things to be agreed on by all.

So did Daumier, whether he meant to or not, see this American taxonomic connection and think there were kangaroos in the Americas?

This marvellous creature that so intrigued Europeans has had a long road from object of curiosity to favoured national symbol. You too can follow the journey of the kangaroo with the descriptions and images that are in the Library's collection.