Before COVID-19 and physical distancing, before bushfires and closed borders, the ‘great Australian dream’ for Australians was most likely a different vision to what it is today. What are our dreams for our country, our families and our lives? What kind of future do we imagine for Australia? In the midst of 2020, we invited three writers to reflect on their hopes, their dreams for Australia after bushfires and pandemics.

Victor Steffensen is an Indigenous fire practitioner of the Tagalaka people of North Queensland. He believes that Australians are too disconnected from the environment and that the land needs to be healed and traditional practices introduced nationwide to help prevent the fire catastrophes that frequent the Australian landscape. His book Fire Country: How Indigenous Fire Management Could Help Save Australia offers solutions to these catastrophes, explaining how the revival of Indigenous fire practices such as ‘reading of country’ and undertaking ‘cool burns’ could help restore the nation.

Victor recounts his experiences with Aboriginal burns, offering insight as to how putting love into the landscape aligns to putting love into ourselves. His dream for the future is that the Australian people will realise that ‘what we are fighting for is priceless’.

Priceless by Victor Steffensen

Today I sit on country in northern New South Wales, helping an Aboriginal community to get their fire programs going. It’s afternoon now and the sun is setting. We are doing another typical gentle fire, burning peacefully in the country. You can hear the birds in the trees, you can see the smoke nice and light. Beautiful burn, low and calm. I can hear the sound of a four-wheel drive coming my way. It's the local Aboriginal rangers checking the fence lines to keep the fire out of the farmers’ paddocks. Today, they are burning around their community, keeping their houses, families and country safe from the bushfire season.

Like all Aboriginal burns, it does so much good for the people and the environment. It’s good to see people on the land, working on country to help heal the social problems that our young people face today. To start healing the trauma that older generations are dealing with too. When we look at the power of connecting to the land, it is priceless. When you look after the country with Aboriginal fire, you are putting love into the landscape and into ourselves. It takes time to care and look after the country—to manage each place the right way so it can be healthy, and to apply the right treatment for places that have become sick. To put love and care into the landscape is an ongoing constant practice, a full-time job that many people would love to do.

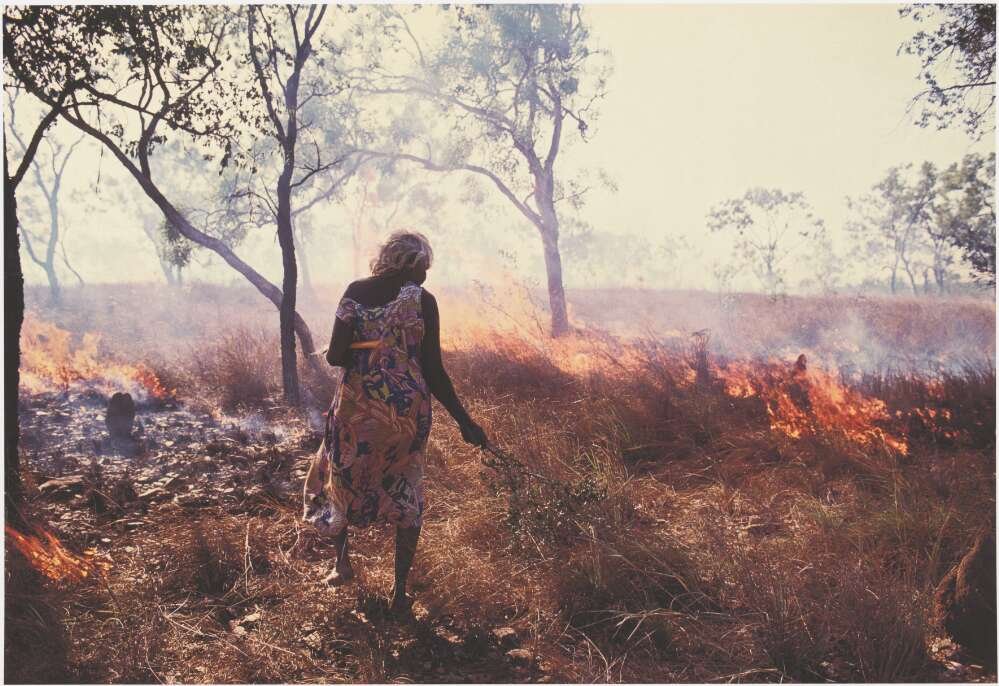

Helga Salwe, The Artist Gertie Huddlestone Cleaning up Country with Controlled Burning, Arnhem Land, 1992, nla.cat-vn6297341.

One of the rangers came up to tell me how engaging with Aboriginal fire and connecting to country has saved his life. He told me how his life was going downhill with drugs, stealing cars and breaking into shops. ‘I would be in prison by now or probably dead,’ he said to me with a big smile on his face. The honest words he shared overwhelmed me with the same beauty of watching the light, gentle smoke dance with the sunlight through the trees. ‘I can’t wait to get this going properly so we can have a hundred young fellas out here looking after the country,’ he said, as he walked off to light a few more little fires. ‘It will happen one day,’ I replied. ‘We just need to keep on going until they finally listen.’

I sat down on my own again to take in the peaceful burn and think about the words that he shared with me. It made me remember a news article that someone sent me a few days earlier. The article quoted some scientist fella saying that Aboriginal fire management was too time consuming and would cost too much money. It was another negative opinion that undermines Aboriginal fire aspirations. I sat there thinking about it for a little while. How can you put a price on the health of our environment and our children of the future?

How do you compare the dollar sign to the wellbeing of our planet and ourselves? Billions of dollars going down the drain every year because of bushfire destruction. Billions are going into the business of fighting fire and still we are grateful for any amount of funding for an Indigenous fire workshop. The total spent on disasters and programs based on the fear of fire is astounding. When you really think about it, it doesn’t make much sense.

The truth is that it will cost a lot of money to create jobs to look after our planet better, but it will also improve the quality of our lives and our home. This has to be better than spending billions reacting to the after-effects of disasters, and the massive social and environmental problems those disasters also entail. We can’t not afford to invest in a better future for our planet, and I think most people would agree. And if you look at it carefully enough, the re-application of Aboriginal fire knowledge can activate many exciting opportunities. If we work with the land, then there will be far greater rewards in the short and long term.

John Flynn, A Bush Fire, Victoria Australia, 1912, nla.cat-vn2373239.

Reviving the Indigenous knowledge system can potentially provide a holistic wave of understanding that can contribute to greater education outcomes. Activating this knowledge base over time will see it improve and help shape positive economic, cultural and social spin-offs. A holistic way of thinking and doing that interconnects many values and roles within our society. This not only relates to fire, but also the wellbeing of our waterways, plants, animals and ourselves. The trick is to involve people in a way that can bring all of the contributing interests onto the same page. To achieve bringing modern world views and mindsets onto the same level of values will be a shift worth its weight in gold.

Mother Nature is best at demonstrating the way that the interconnected relationships between all resources work together to create ongoing survival. The actions of one creature can support life for many more, and that effect continues on from one living thing to the next. When these positive gestures are multiplied by thousands of thoughtful creatures, we end up with an eternal web of abundance of giving and receiving that enables life to thrive. If we look at the reasons why Aboriginal people want to bring back traditional fire practices alone, we see the same interconnected pattern.

Bringing back the cultural fire for Aboriginal people will help to revive culture and see health benefits; improve social relationships; heal and manage the land and waters; create employment and educational opportunities; support economic ventures like medicines and bush foods; express artistic interpretation, spirituality, women’s and men’s programs; improve agriculture and regenerative practices, including seed harvesting, which will decrease the number and severity of bushfires; and the list goes on—and will keep surprising us into the future.

All of these aspirations are living examples that have come from the cultural fire movement in Australia within the last two decades. But if we look at the current western fire management, it is more reactive than proactive. This leads to mainly investing in hazard reduction burns, and evacuations in the name of fighting a war against fire. We can either waste billions of dollars being afraid of fire or we can put a fraction of that cost towards positive growth for a better future. The notion seems so simple, yet it is so hard for many to comprehend. The thing is, we have no choice but to start investing in people and country; we can’t continue the think and act the way they do.

Sean Davey, Rural Fire Service Volunteers Fight a Bushfire on the Lans Family Property on Little Bombay Road, Braidwood, New South Wales, 2019, nla.cat-vn8408338.

I know it may be hard for many people to understand, but money should never be worth more than any of Earth’s precious life forms. Nor should it dictate the decisions we make about what is unconditionally our responsibility to who we are and where we live. Our priorities should be based on advancing our culture and knowledge into healthy landscapes and communities. Finding exciting ways for the economy to evolve with that should be high on the agenda. If we are serious about the challenges we face today and into the future, then we should be listening and adapting to other ways to see the world.

I sat and thought about all this a little longer, before one of the rangers called out to me to finish the day. The fire was nice and calm as it worked its way through the last bits of dry grass. I stood up and walked towards the rangers waiting for me, who were beaming from ear to ear. ‘Jump in the car and we will give you a lift home.,’ they said happily. I got in, making a few jokes, and we drove off, admiring the last views of the gentle fire. ‘Beautiful burn today—you can see all the birds coming in to thank us,’ said one of the rangers. ‘I wish I could do this for the rest of my life, it feels good to be a part of the land.’

There was a brief silence as we bounced around in the car, along the beaten track. One of the rangers then went on speaking. ‘I can’t say how important this is for my people. I can’t tell you how hard it has been for us to try and get our culture back. This is the answer for us, get back onto country and start living with it again. Money means nothing to us if we can’t have a healthy land and culture. I can’t stand back and watch our people slowly die anymore, I tell you, I can’t do it.’ He started to cry next to me as we drove along. ‘I’m sorry, my brother, I just can’t help it,’ he said, as he wiped away his tears. ‘It’s okay,’ I said in a comforting way. ‘One day the support will come, once people realise that what we are fighting for is priceless.’

Further reading and resources

- Find Victor Steffensen's Fire Country: How Indigenous Fire Management Could Help Save Australia

- For further information about the history of Indigenous fire practices, read Fire and the Story of Burning Country

- Find out more about fire management in Australia

- Read Part 1 and Part 2 of the Summer Long Reads series