As a curator, what you see in certain objects tends to evolve and change over the life cycle of an exhibition. Events over the past six months have certainly changed the way I look at and respond to the images in Australian Dreams: Picturing Our Built World, particularly those of Melbourne. This is fitting, because the exhibition itself explores how some of Australia’s greatest painters, printers and photographers have interpreted our built environment. Because of the lockdown, I have become increasingly aware of the people in the pictures of Melbourne and how they are interacting with the buildings and streetscapes on show.

Samuel Thomas (S.T.) Gill (1818–1880), Royal Arcade, Melbourne, c.1870, nla.cat-vn1980274.

Let’s start with some images from the exhibition that celebrate the iconic structures of the city and their centrality to public life. For instance, the watercolour of the Royal Arcade by the popular and versatile S.T. Gill not only illustrates the formal beauty of Australia’s oldest extant shopping arcade, but also the theatrical interaction between people and the built environment. The street outside the arcade is a grand stage on which the Melburnians of 150 years ago pranced, paraded, gossiped and gazed at each other.

Another iconic gathering place for Melburnians is the much-loved Sidney Myer Music Bowl, the great span of its canopy captured below by Maggie Diaz, a commercial photographer who immigrated from the United States and worked mostly in Melbourne. It may be empty for Carols by Candlelight this year, but hopefully it won’t be long before the crowds come flocking back to enjoy the music, show off their headwear and just revel in the pleasure of being part of a big gathering.

In the photo of Flinders Street Railway Station by Mark Strizic, one of the leading architectural photographers working in Melbourne during the 1960s, the entrance to the station dominates the image. But what makes it come alive is how the photographer has captured the hustle and buzz of Melburnians crisscrossing the intersection in front of the entrance. Perhaps it’s the awareness of their absence for so much of the year that makes the crowds in these three images stand out and also reinvigorates the depictions of the structures where they work and play.

Left: Maggie Diaz (1925–2016), Audience at the Myer Music Bowl, Melbourne, c.1965, nla.cat-vn6001047; Right: Mark Strizic (1928–2012), Intersection of Swanston and Flinders Street, Flinders Street Station, Melbourne, January 1964, nla.cat-vn734628.

The exhibition isn’t all celebrated buildings and large crowds. Australian artists have been just as interested in the commonplace, capturing buildings where everyday lives played out. In another photo by Strizic, I was initially interested in the compositional elements, the way the Victorian era terraces were contrasted with the Gotham City-esque style of the Russell Street Police Headquarters. But more recently I’ve been drawn to the chap pensively looking out from his balcony and wondered, ‘what’s he looking at? What’s he thinking about?’ Similarly, in the small oil painting Spencer Terrace, Melbourne by David Davies, I at first focused on the impressionistic rendering of the buildings on this empty suburban street in Melbourne. But increasingly my attention turned to the barely perceptible figure out the front of one of the houses. What’s her story? Is she coming or going, or perhaps just stepping out for some air? Is she even real? Perhaps she’s a ghost?

Mark Strizic (1928–2012), Row of Victorian Terrace Houses in Albert Street, East Melbourne, October 1963, nla.cat-vn734466.

David Davies (1864–1939), Spencer Terrace, Melbourne c.1925, nla.cat-vn284494.

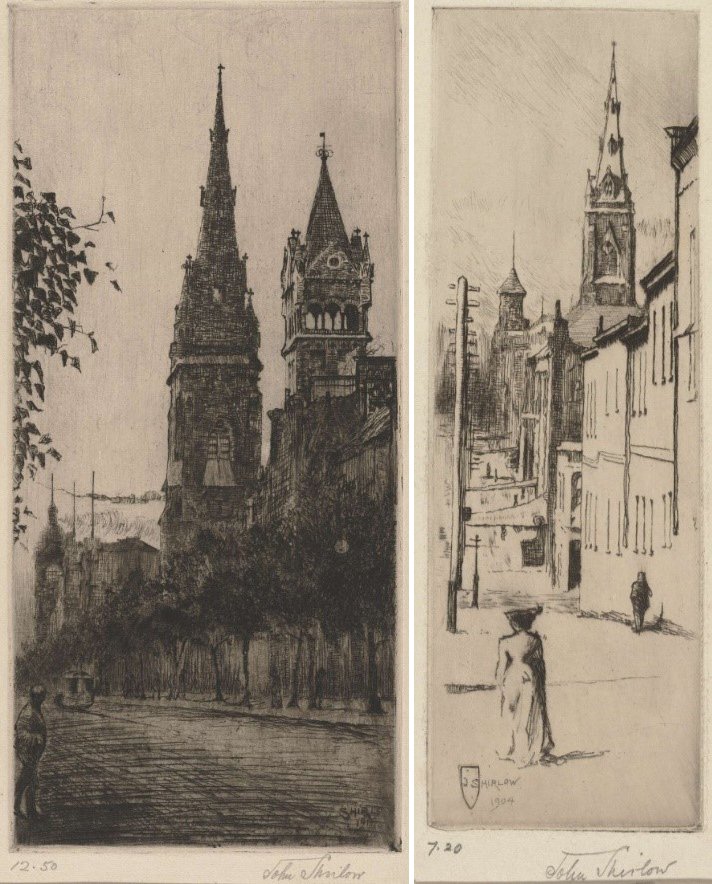

People are actually out on the streets in the work of John Shirlow, one of the first Australian artists to make etching the focus of his artistic practice. I selected these images for the exhibition because they seemed to show a moodier, more atmospheric side of Melbourne’s streetscapes and buildings. But now his solitary figures draw my attention, hiding in the shadows or, seemingly, keeping their distance from each other on the streets.

Left: John Shirlow (1869–1936), The Gothic Spire, Melbourne, 1914 in Collection of Fifty Etchings of Melbourne 1895–1915, nla.cat-vn8129572; Right: John Shirlow (1869–1936), Russell Street, Melbourne, 1904 in Collection of Fifty Etchings of Melbourne 1895–1915, nla.cat-vn8129393.

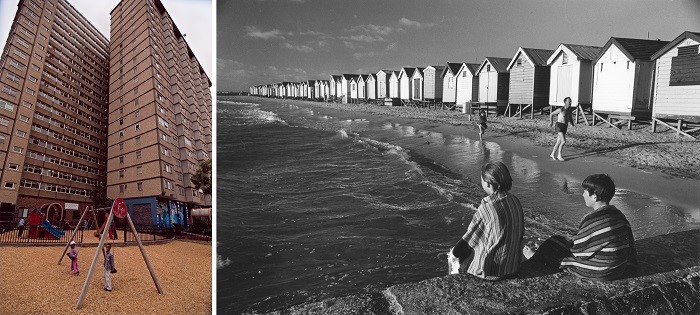

One of the more arresting images in the exhibition wasn’t of individuals cowering in the shadows or a revelling crowd, it was a photograph by Walkley Award–winning photographer Dave Tacon of children playing outside of one the housing commission towers in Flemington. The towers were subject to some of the most severe lockdowns in the city and it is impossible to look at the photograph now without reflecting on empty playgrounds and families stuck inside.

Thankfully, things are starting to return to some kind of normalcy in Melbourne. With the school holidays approaching, how brilliant it will be for children and families to leave the city for a while. Perhaps they’ll got to a beach lined with iconic timber beach bathing boxes, a feature of many of the beaches around Port Phillip Bay, like in the picture by photojournalist Jeff Carter. And I look forward to returning to Melbourne to visit family and friends – and to see some of my favourite buildings in the flesh. Have a Happy New Year, Melbourne. You’ve earned it.

Left: Dave Tacon (b.1976), Children on Play Equipment at the Housing Estate at 120 Racecourse Road, Flemington, Victoria, 15 March 2006, nla.cat-vn3701153; Right: Jeff Carter (1928–2010), Beach Houses at Black Rock, Port Phillip Bay, 1965, nla.cat-vn1849342.

Australian Dreams: Picturing our Built World

- Watch a two-part online tour of the exhibition with curator Matthew Jones

- Uncover the idea behind the exhibition

- Learn about 'Old Sydney' and the architectural influences on early 20th century Australian art

- Attend the exhibition