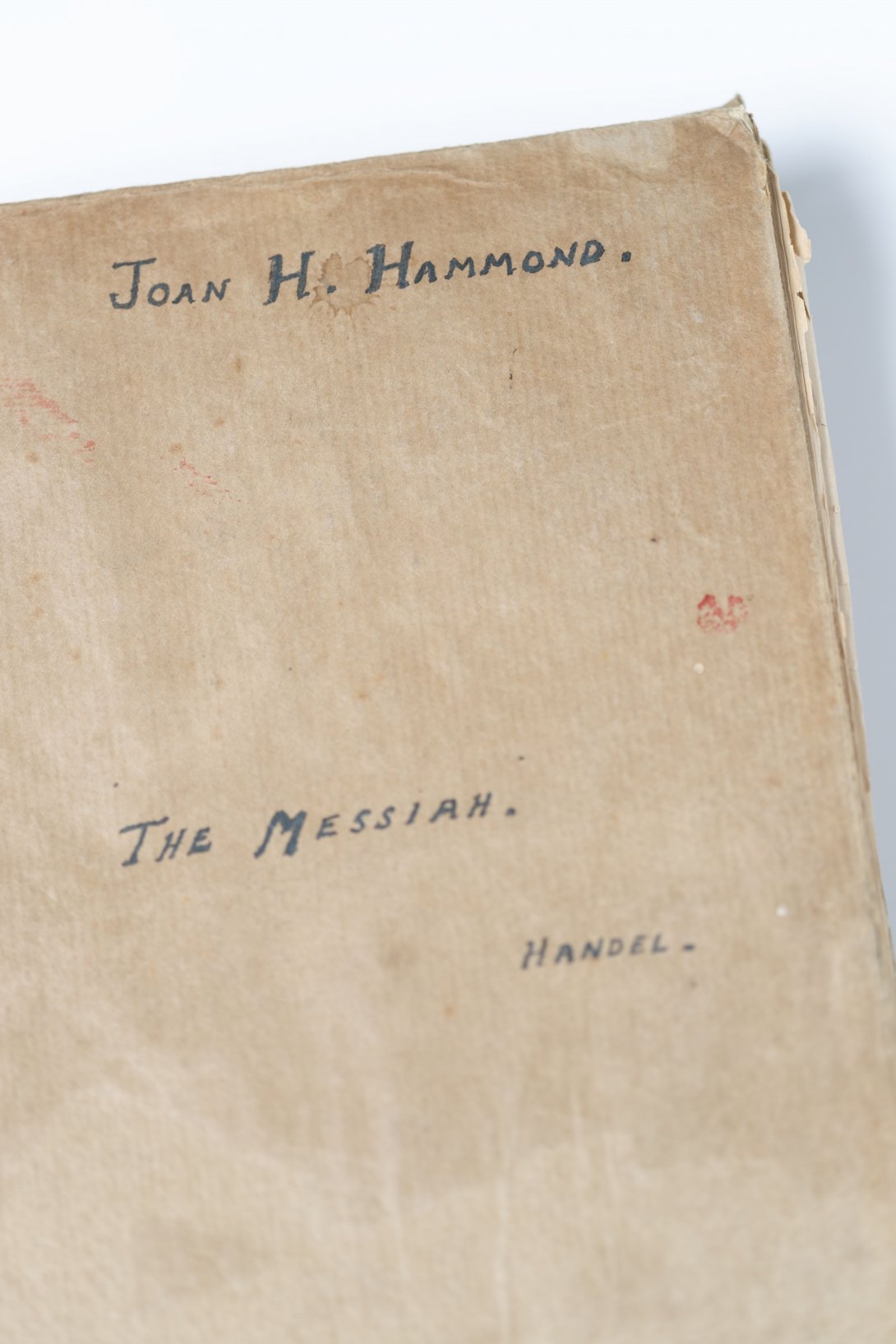

Just before Christmas in 1938, young Australian soprano Joan Hammond (1912–1996) performed in Handel’s Messiah in London, under legendary British conductor Sir Thomas Beecham.

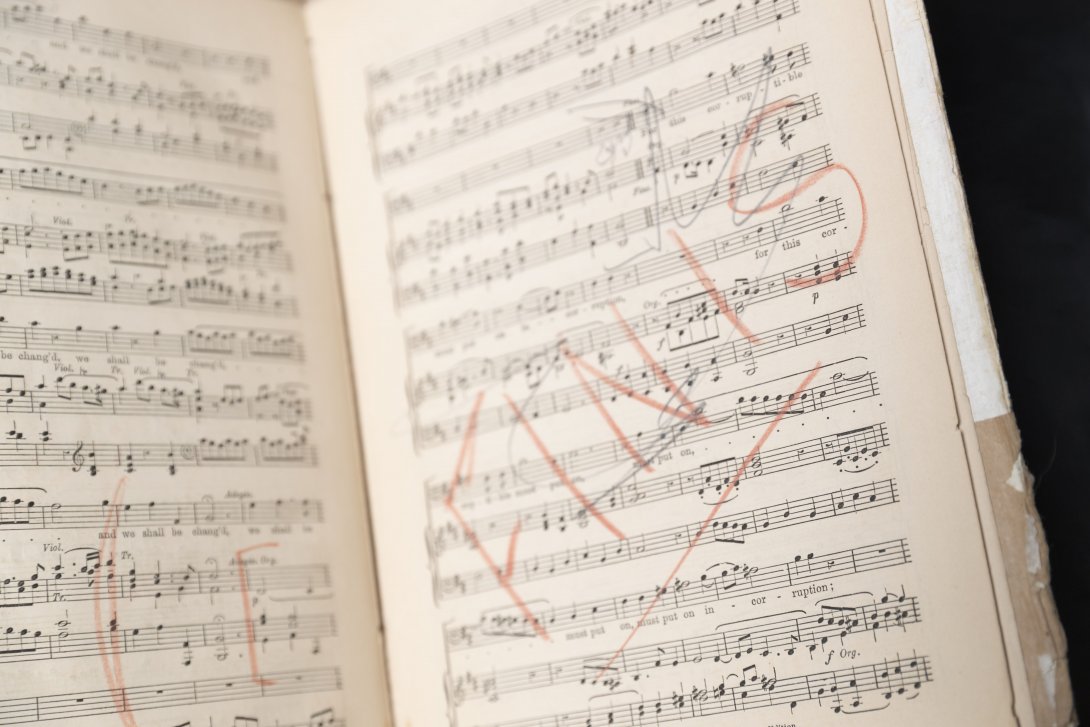

The West Australian relayed the London reviews, quoting the Daily Mail: ‘Her ‘Messiah’ may be the beginning of great things.’ Hammond, later Dame Joan Hammond, did go on to great things, becoming one of Australia’s most acclaimed opera exports of the twentieth century, as well as a champion golfer. The National Library holds Hammond’s copy of the Messiah. It has been well used, with abundant sticky tape and coloured pencil annotations. Some of the inscriptions are so large, you can read them from a distance, as Joan must have. Note to reader – sticky tape does not age well.

In this blog, Rare Books and Music Curator Dr Susannah Helman explores the Library’s holdings of what has become a classic Christmas work, and early editions of other works by the German-born English composer George Frideric Handel (1685–1759). Born in Halle, the son of a barber surgeon, Handel was inspired by opera at an early age, moving to Hamburg in his late teens, to Italy in his early twenties, and to London in his mid-twenties where he settled, was celebrated, and remained for the rest of his life.

Musicologist Charles Burney (1726–1814), father of novelist Fanny Burney, knew Handel in his fifties and described him this way:

The figure of Handel was large, and he was somewhat corpulent, and unwieldy in his motions; but his countenance, which I remember as perfectly as that of any man I saw but yesterday, was full of fire and dignity; and such as inspired ideas of superiority and genius. He was impetuous, rough, and peremptory in his manners and conversation, but totally devoid of ill-nature or malevolence: indeed, there was an original humour and pleasantry in his most lively sallies of anger or impatience, which, with his broken English, were extremely risible. His natural propensity to wit and humour, and happy manner of relating common occurrences, in an uncommon way, enabled him to throw persons and things into very ridiculous attitudes.

Burney, Account, Sketch, 31–2 in Grove Music Online

Though Handel had varied output, he has become most associated with the English oratorio form, which he established, and his most famous work, the oratorio The Messiah, first performed in Dublin in 1742. Grove Music Online defines an oratorio as ‘[a]n extended musical setting of a sacred text made up of dramatic, narrative and contemplative elements’. The ‘Hallelujah Chorus’ is its most famous chorus. Its manuscript famously belonged to George III – and was transferred to the British Museum (later the British Library) in 1957.

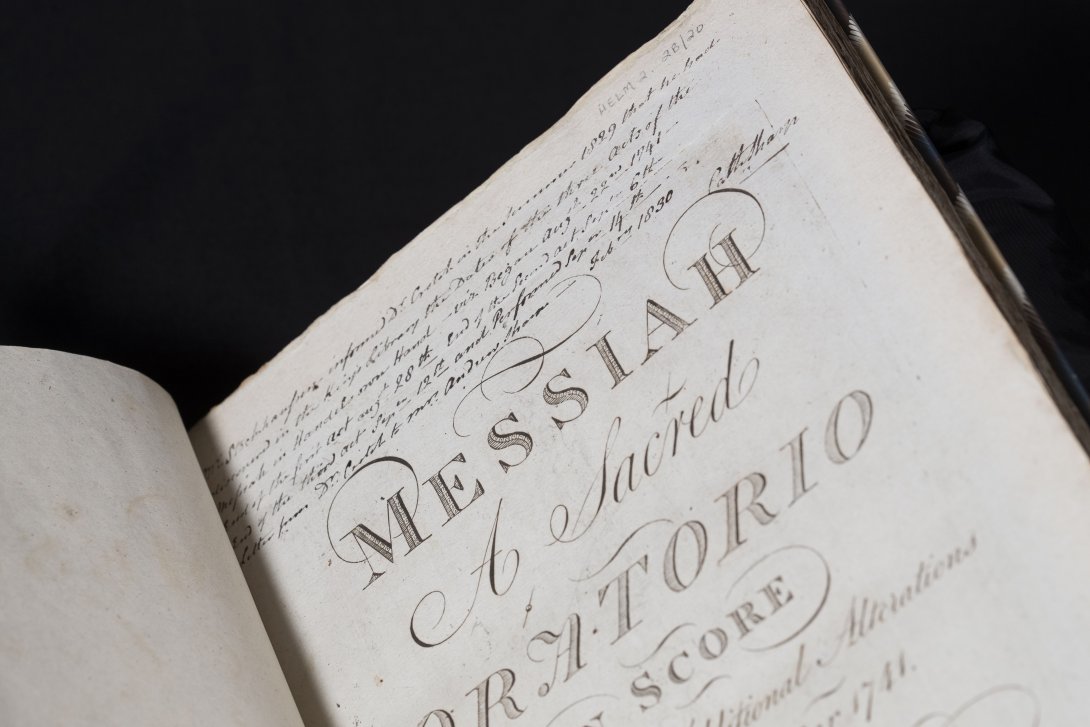

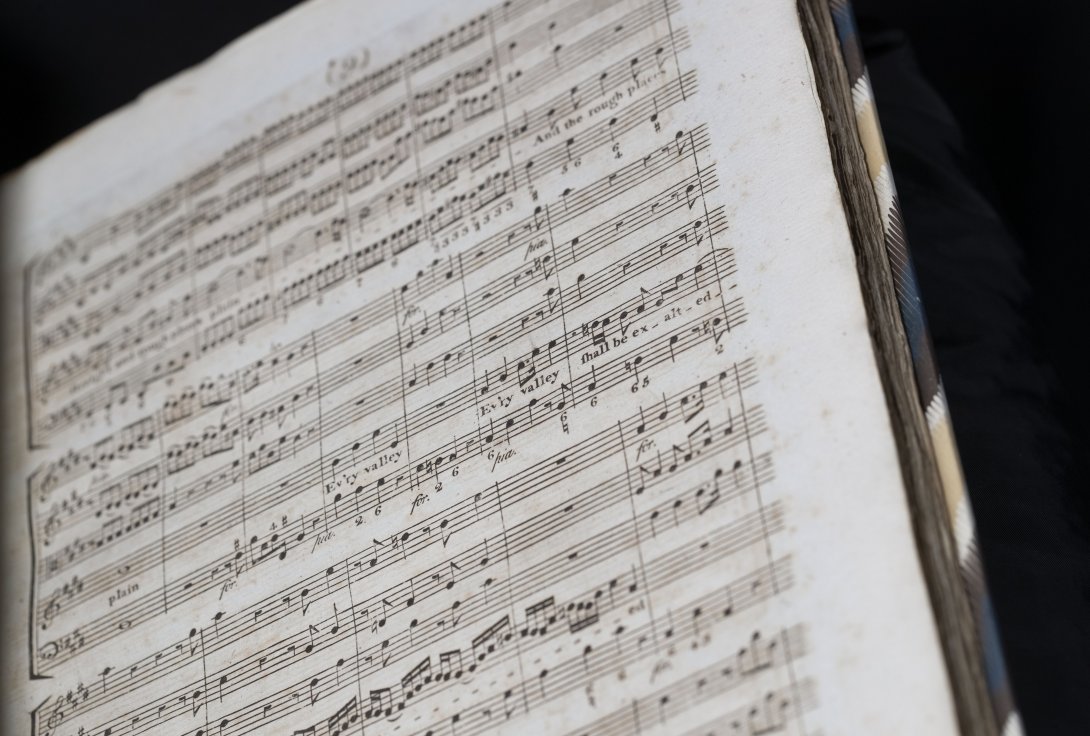

While the Library holds a number of early libretti – the words – of The Messiah, one of the earliest full musical scores is Samuel Arnold’s edition of 1787 or 1788.

Arnold attempted to publish Handel’s complete works – an enormous but important task. The project was not fully completed. What is interesting about this copy, however, are the annotations. They were made by a British woman called Catharine Sharp – an annotation says the score was a gift from her mother. In her longer inscriptions, she refers to two letters sent by her former teacher ‘Dr Crotch’, former celebrity child prodigy William Crotch, that a Mr Stockhausen had ‘discovered in the King’s Library the Dates of the three Acts of the Messiah in Handel’s own Hand’. Access to Handel’s manuscript score was closely guarded at this time.

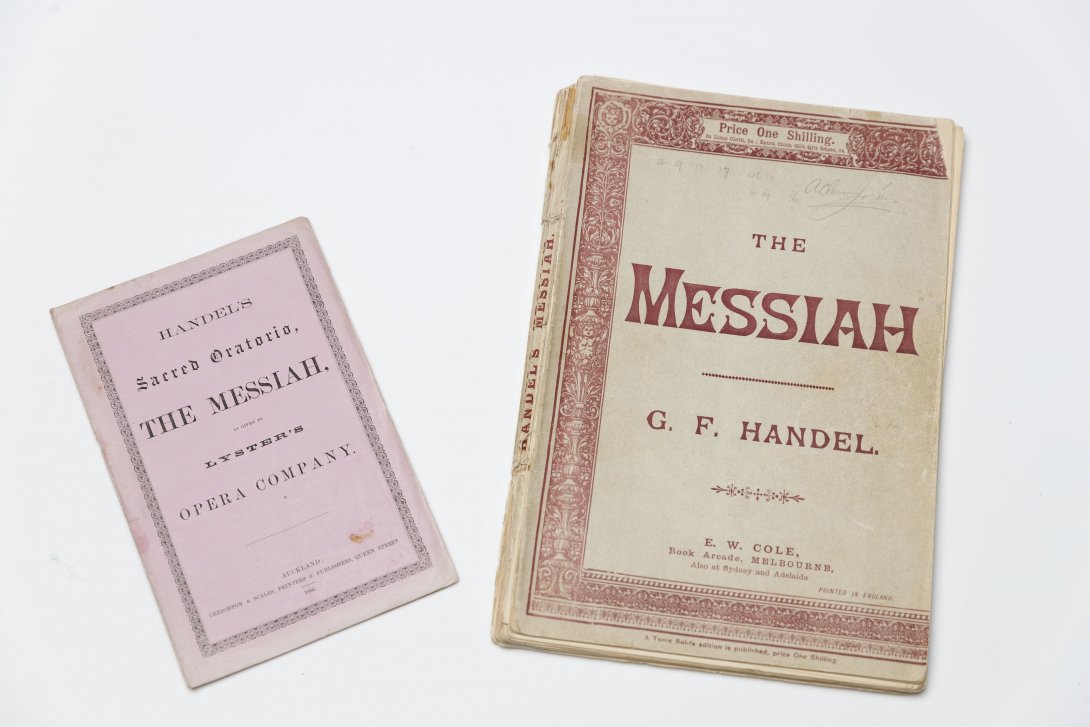

The Library holds early Australasian editions of the libretto (the words) of The Messiah.

On the left is the libretto issued by Australia’s first permanent opera company – W.S. Lyster's company of the 1860s and 1870s. It was printed for a performance in Auckland on 17 December 1864. Joined by singers from Auckland, The Messiah was the last of an exhausting 30 performance run. The Daily Southern Cross newspaper lamented their departure: ‘The pleasant evenings with the Lyster Opera Company have at length been brought to a close. … For sublimity and popularity this oratorio has hardly a rival.’ The National Library of Australia holds a good collection of material relating to Lyster’s opera company, including scores used by the company, and caricatures of the performers. The other is a libretto sold by eccentric 19th-century Melbourne bookseller, E.W. Cole, publisher of the rare Cole's Funny Picture Book.

Among over 850 works by or about Handel, the Library holds first or early editions of some of Handel's other choral works. Italian opera was a cornerstone of Handel’s life and work for many years. It is often said that Handel was not very interested in overseeing the printing of his works.

Nonetheless, they are often quite beautiful.

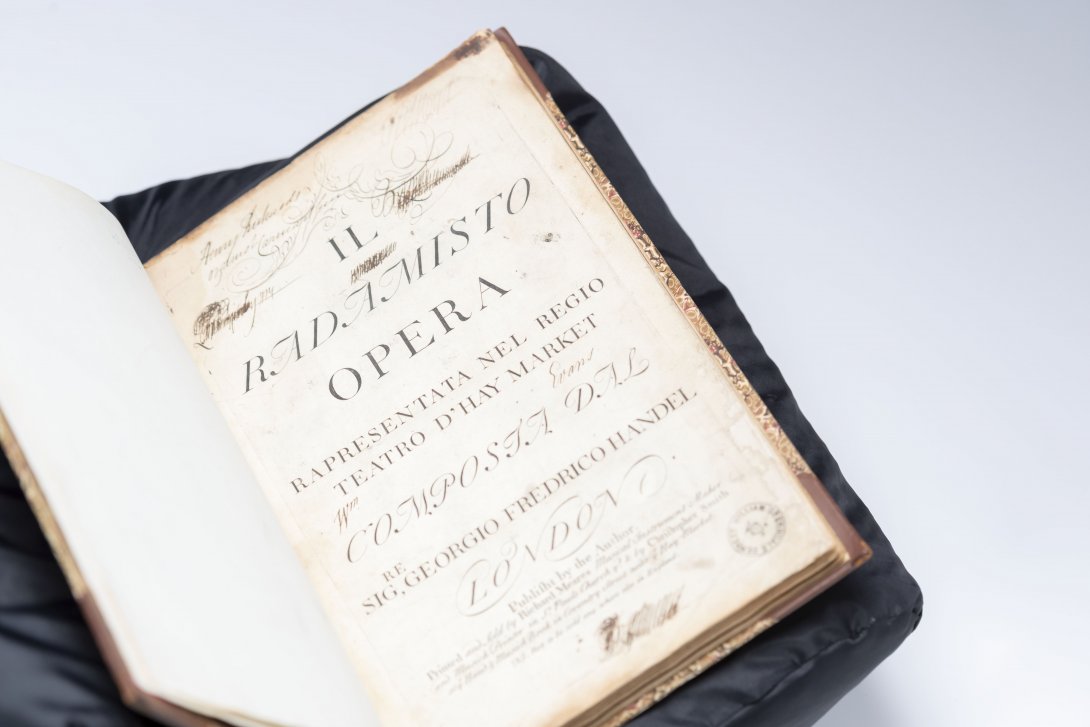

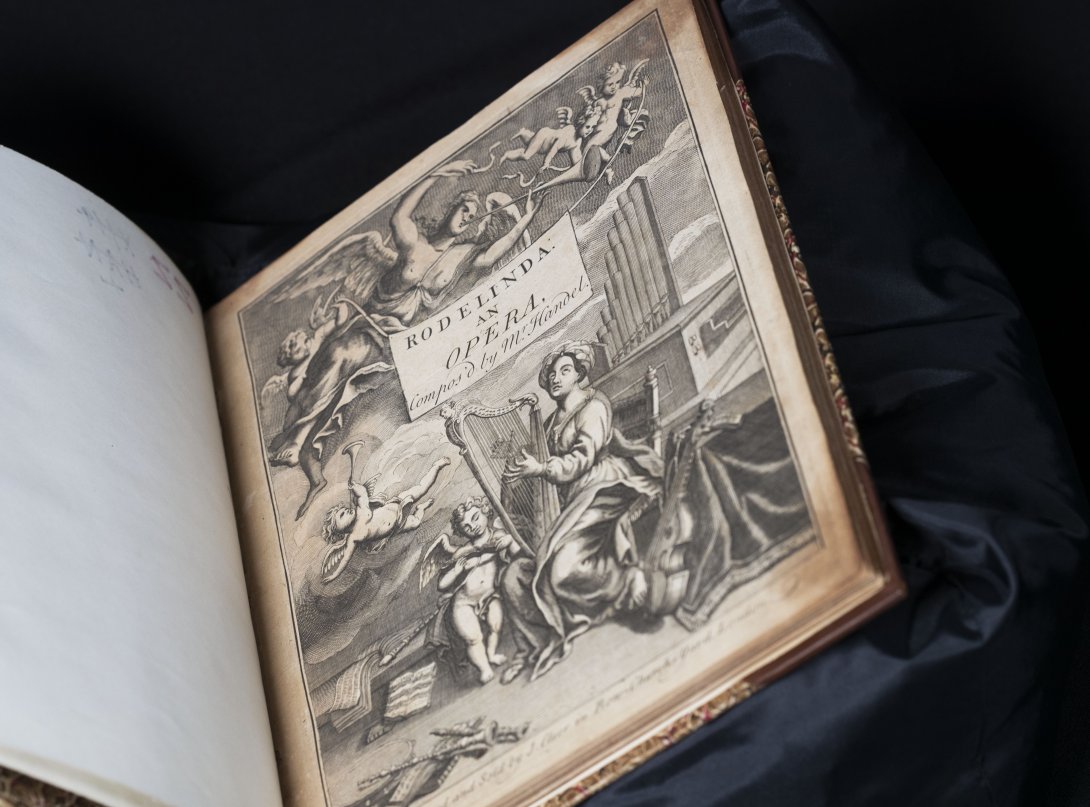

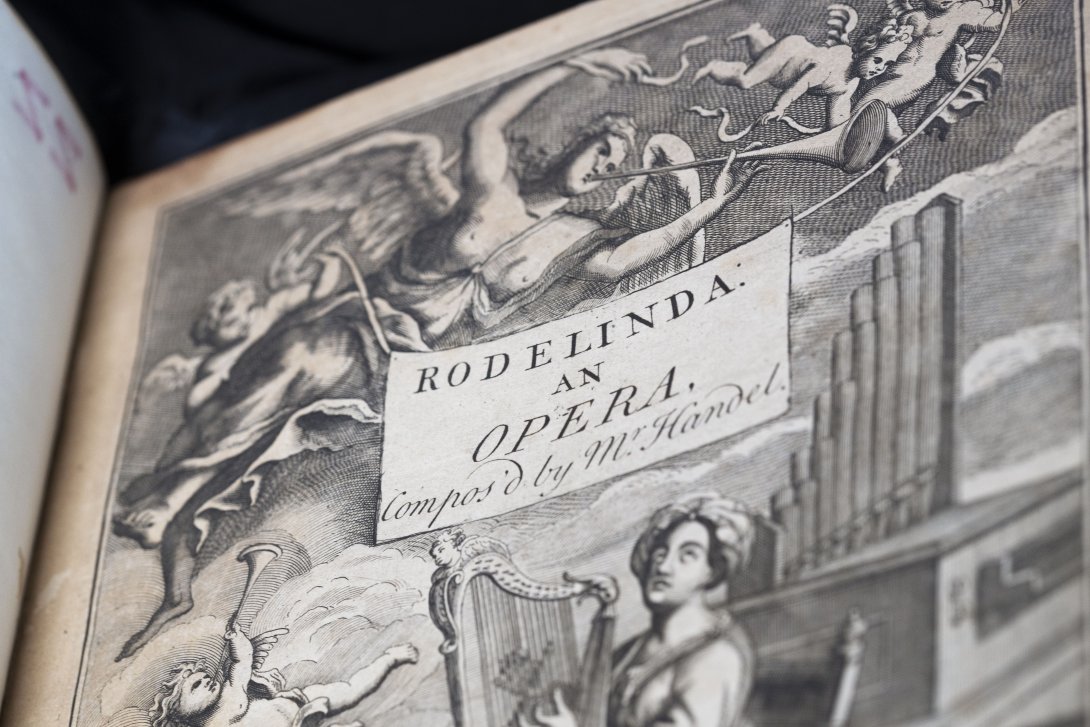

Two opera scores discussed below come from the collection of the English conductor and composer Sir Eugene Goossens (1893–1962), who for just under a decade after the Second World War was both Chief Conductor of the Sydney Symphony Orchestra and also Director of the New South Wales Conservatorium of Music, making a huge contribution to musical life in Australia. He resigned his posts in 1956 under a cloud. It is hard to know whether the scores were used by Goossens or merged afterwards with his working scores when part of the Australian Broadcasting Commission Federal Music Library. This library later became part of the National Library’s collection as part of the Symphony Australia Collection. What is certain is that both are examples of early work by Handel, published by highly regarded printers, with copperplate engraving music and illustrations. Handel’s usual printer from 1730 was John Walsh (c. 1665–1736).

Radamisto premiered in London in April 1720. It was Handel’s first opera for London’s new Royal Academy of Music, and its first performance was attended by both King George I and the Prince of Wales. It drew on a first-century story Roman historian Tacitus told in his Annals of Imperial Rome, in which the King of Armenia falls in love with his wife’s brother’s wife, Radamisto. This copy of Radamisto was printed by Richard Meares, described on the title page as ‘Musical-Instrument-Maker and Musick-Printer’ in St Paul's Church Yard – long a centre for publishing in London and by Christopher Smith ‘at ye Hand & Musick-Book in Coventry-Street near ye Hay-Market’. This was a period when shop signs relied on images rather than words, as many people were illiterate. You would have seen a sculpture or other image of a ‘hand’ and ‘music book’ above the entrance to the shop. Richard Meares (c. 1671–c.1743) and his father (d.c.1722), also Richard, were instrument makers, music publishers and sellers. The elder specialised in instruments, while the younger made violins yet focused on publishing. Radamisto is considered a highlight of their work.

The London newspaper, The Post-Man and the Historical Account, advertised it this way on 5 January 1721. Clearly the newspaper’s compositors were in a rush, as there are numerous mistakes…

ADVERTISEMENTS.

With his Majesty’s Royal Privilege and Licence,

The Celebrated OPERA of RADAMISTUS

composed and correctected [sic] by Mr. Handel, and curiously Engraven on a Hundred and Twenty Three Copper Plates; printed upon a fine Dutch Paper, and the best most correct Piece of Musick extant; is now publish’d by the Author, and Sold by Richard Meares, Musick Printer, at the Golden Viol and Hautboy in S. Paul’s Church Yard. And whereas Mr. Handel has composed several Additional Songs to mae [sic] the said Work more compleat, they will be added to the Book, which will be Sold at the same Price as before; and such Gentlemen and Ladies as have already purchased it, may have the Apditions [sic] Gratis at the Place above mention’d: Where also Mr Handel’s Lessons for the Harpsichord are sold. N.B. The Newest songs are now Engraving, and will speedily be delivered.

Next is the score for Rodelinda, an opera first performed in London at the King’s Theatre Haymarket on 13 February 1725 for the Royal Academy of Music. Using the 8th-century work of historian Paul the Deacon as source material, it tells the story of Rodelinda, Queen of the Lombards and Bertarido, her dethroned husband. It ended a very busy and successful 12 months for Handel – he premiered 3 operas, all well-received.

Subscribers financed the printing of Rodelinda. Advertisements for subscribers were taken out in London newspapers, such as this in London’s The Evening Post on 20 March 1725:

The whole OPERA of RODELINDA, in Score, with all the Parts. In above 100 Copper Plates. Compos’d by Mr. Handel. The Quality, &c. who design to Subscribe to this celebracted [sic] Opera, are desired to send their Names in 20 Days at farthest, otherwise they can’t be Engrav’d in the Book.

It is one of a number of Handel operas Cluer printed at this time – including Tamerlane and Julius Caesar.

The printer, John Cluer, only began to focus on music printing in the 1720s – with pharmacy as an interesting sideline. The beautiful frontispiece, probably by Cluer’s foreman Thomas Cobb (who later married Cluer’s widow), was actually printed from the same plate used for Handel’s 1724 opera Tamerlane – just the title banner was updated. This duplication was perhaps appropriate – the first London performances of Rodelinda and Tamerlane had the same cast, including the soprano Francesca Cuzzoni and alto castrato Senesino (Francesco Bernardi). Senesino was a superstar of London’s operatic stage – he performed in no fewer than 20 of Handel’s operas – originating 17 roles, though theirs was a fiery relationship. Handel once called Senesino a ‘damned fool’.

Handel was also a philanthropist, a benefactor to London’s Foundling Hospital. He performed in fundraising concerts for them and left bequests in his will, including a fair copy of The Messiah to the Hospital.

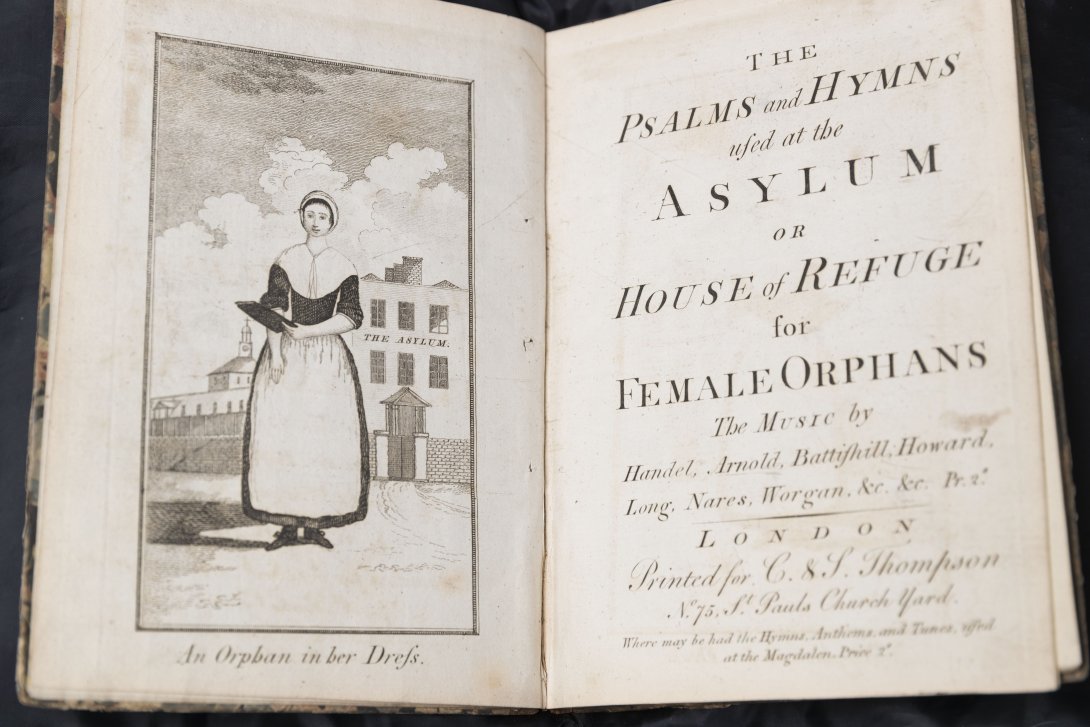

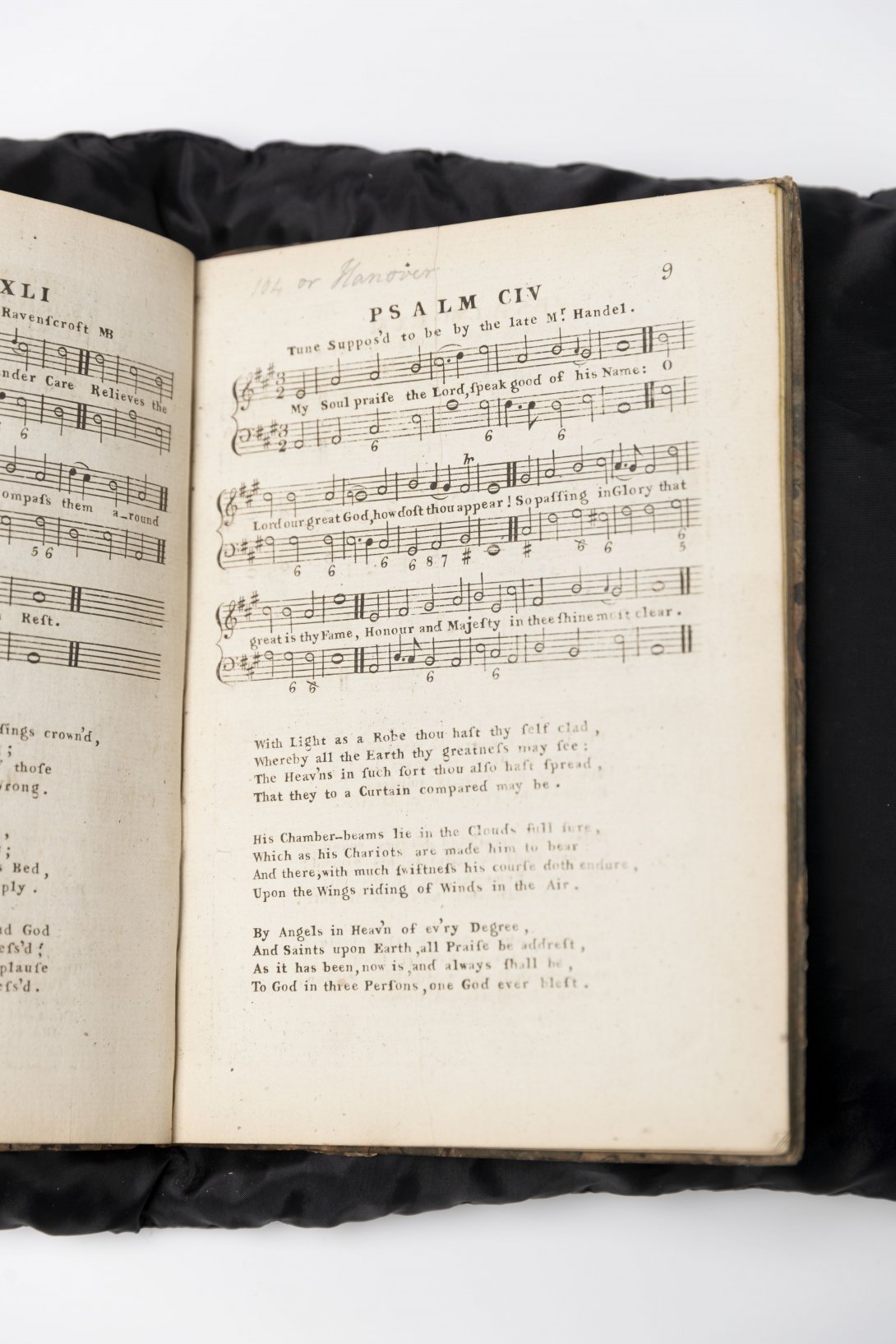

This book of psalms and hymns has been called a pirated edition of a work first published in 1767. One of the works is by Handel, who has top billing in the list of composers.

There are many rabbit holes to go down in the music collections of the National Library. And this is just one of them. The collection offers glimpses into the life and work of Handel and many other composers whose work is performed widely today, and insights into the printing and publishing of music and its performance in Australia and overseas, then and now.

Season’s Greetings! Wishing ‘great things’ for you in 2023.