Due to scheduled maintenance, the National Library’s online services will be unavailable between 8pm on Saturday 7 December and 11am on Sunday 8 December (AEDT). Find out more.

Aboriginal, Torres Strait Islander and other First Nations peoples are advised that this post will contain images and names of deceased people and other content that may be culturally sensitive. The views/language used by collection material highlighted in this blog do not reflect the views of the National Library today.

Today marks 10 years since the first Nelson Mandela International Day was celebrated by the United Nations. The basis of this day is not only to celebrate the life and legacy of Nelson Mandela, but to inspire others to make a difference in their communities. The spirit of Nelson Mandela emphasises that absolutely anyone can be a change maker, with Mandela himself claiming that ‘it is in your hands to make of our world a better one for all’.

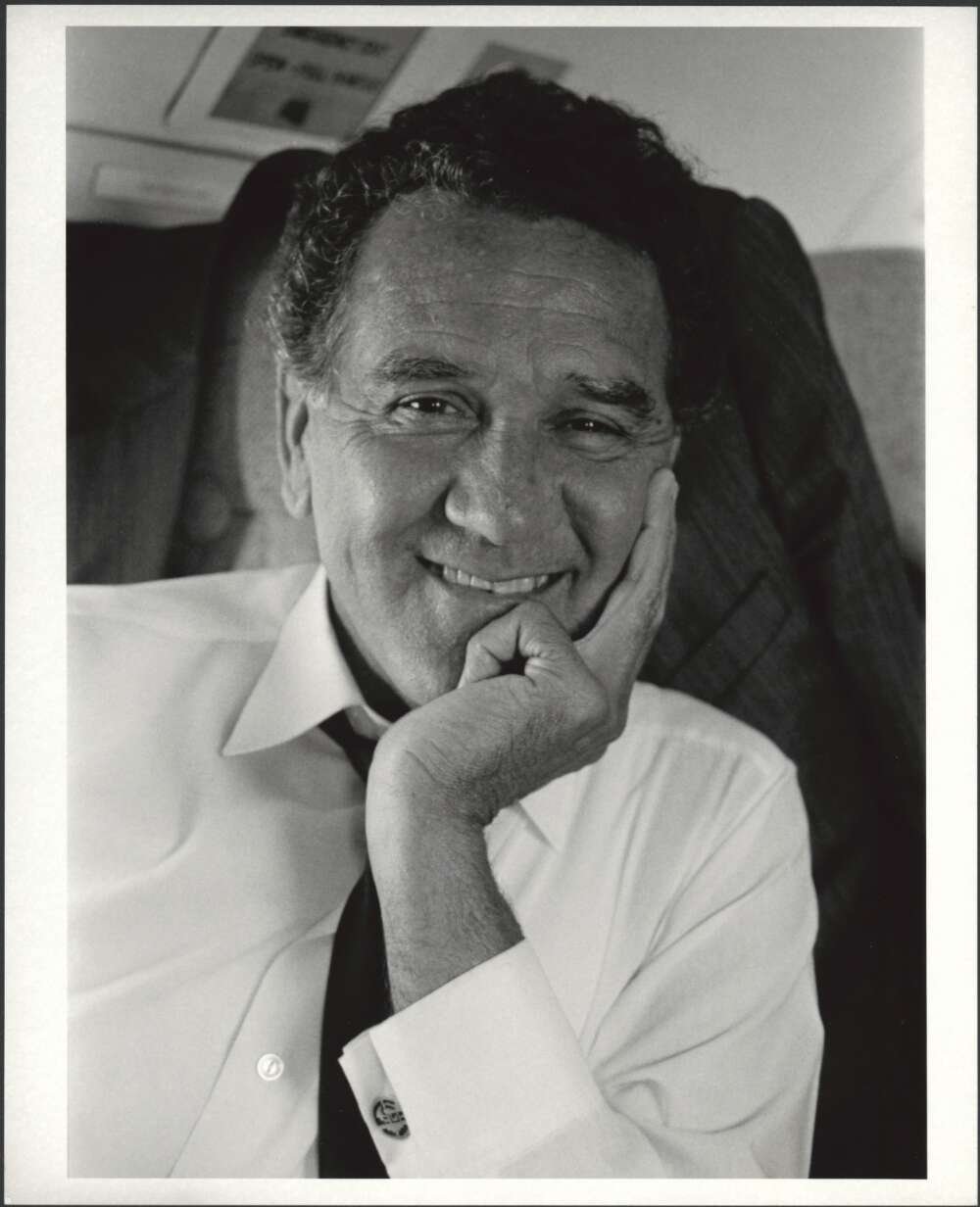

Joyce Evans (1929-), Portrait of Charles Perkins, 1987, nla.cat-vn3563026

Today I think it is fitting to talk about the Mandela spirit from an Australian perspective, and to also think about how the work of one of our own echoes that of Mandela. That person is Charles Perkins. In their own ways, both Nelson Mandela and Charles Perkins dedicated their lives to enacting meaningful and sustainable change for their people and, to an extent, the wider world.

Charles Perkins was born near Alice Spring between 1936–1937 on a table at the Alice Springs Telegraph Station. In his autobiography, Perkins talks about the difficulties individuals had in Alice Springs connecting to their Aboriginal heritage and, particularly, his own difficulties to do so. Due to government policies at the time separating 'part Aboriginal' children from family living on reserves, Perkins only met his grandmother once through the reserves fences. Aspects of his early life, including his separation from his people and culture, drove Perkins to the realisation that something was not right, and further motivated him to achieve goals that had been mostly unobtainable for other Indigenous Australians.

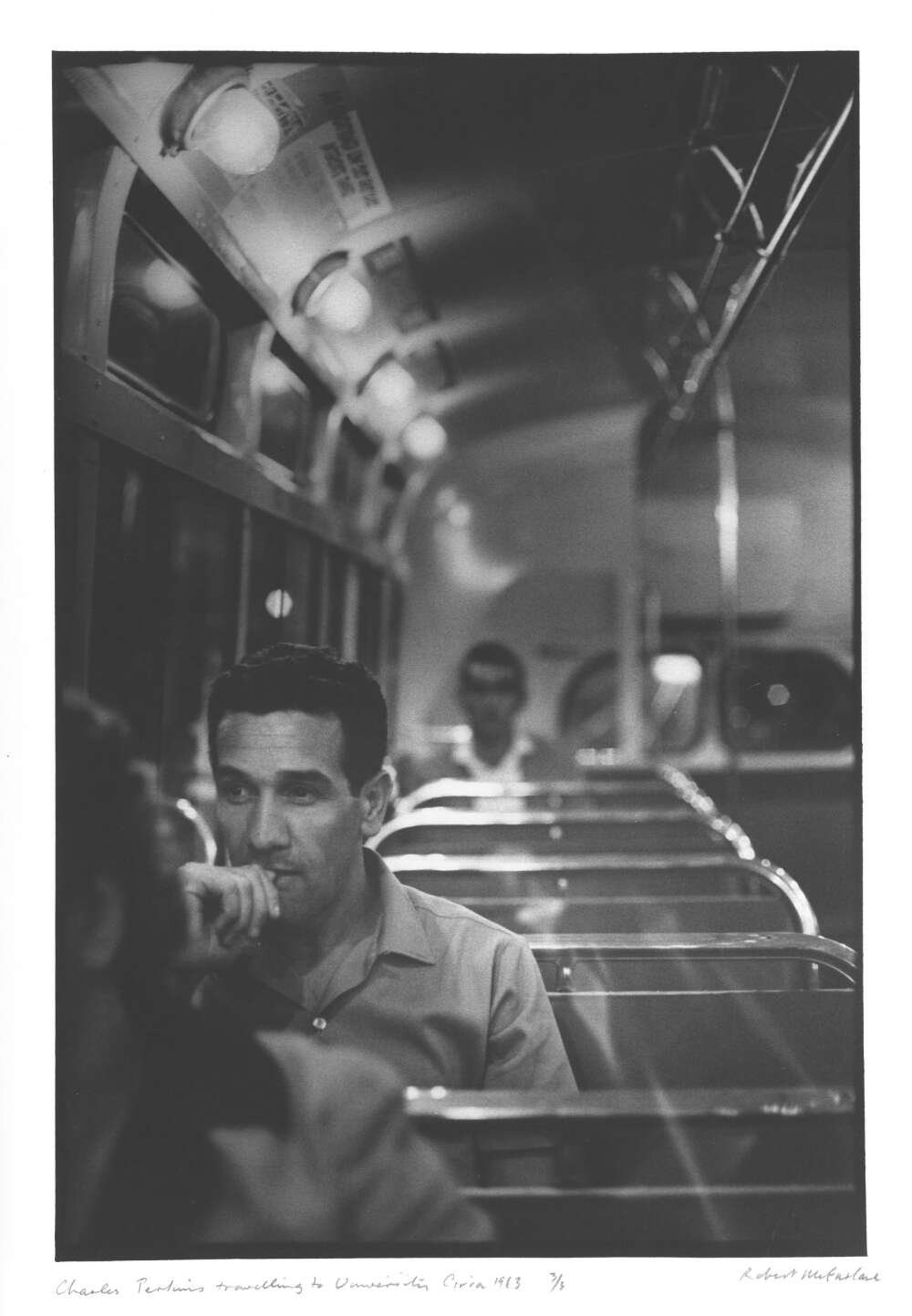

Many would know about Perkins’ achievement as the first Aboriginal man to graduate from university. He saw his accomplishment of graduating university anti-climactic, with the real challenge being figuring out how to use his newfound education to better the lives of his people across the nation. He purposefully studied subjects such as anthropology and political science so that his work in the area of Aboriginal Affairs could be as effective as possible.

Robert McFarlane (1942-), Charles Perkins Travelling to University, 1963, nla.cat-vn1626174

During his university experience, Perkins was a pioneering figure in the Australian Freedom Rides around Central New South Wales towns such as Walgett and Moree, where racial segregation was widespread. The Freedom Rides were a new and confronting way to make others aware of the poor living conditions and rampant racism affecting Aboriginal people in country New South Wales towns. The movement gathered both national and international attention. While at university, Perkins also helped establish the Foundation for Aboriginal Affairs in Sydney and was made manager as soon as he finished his final exams.

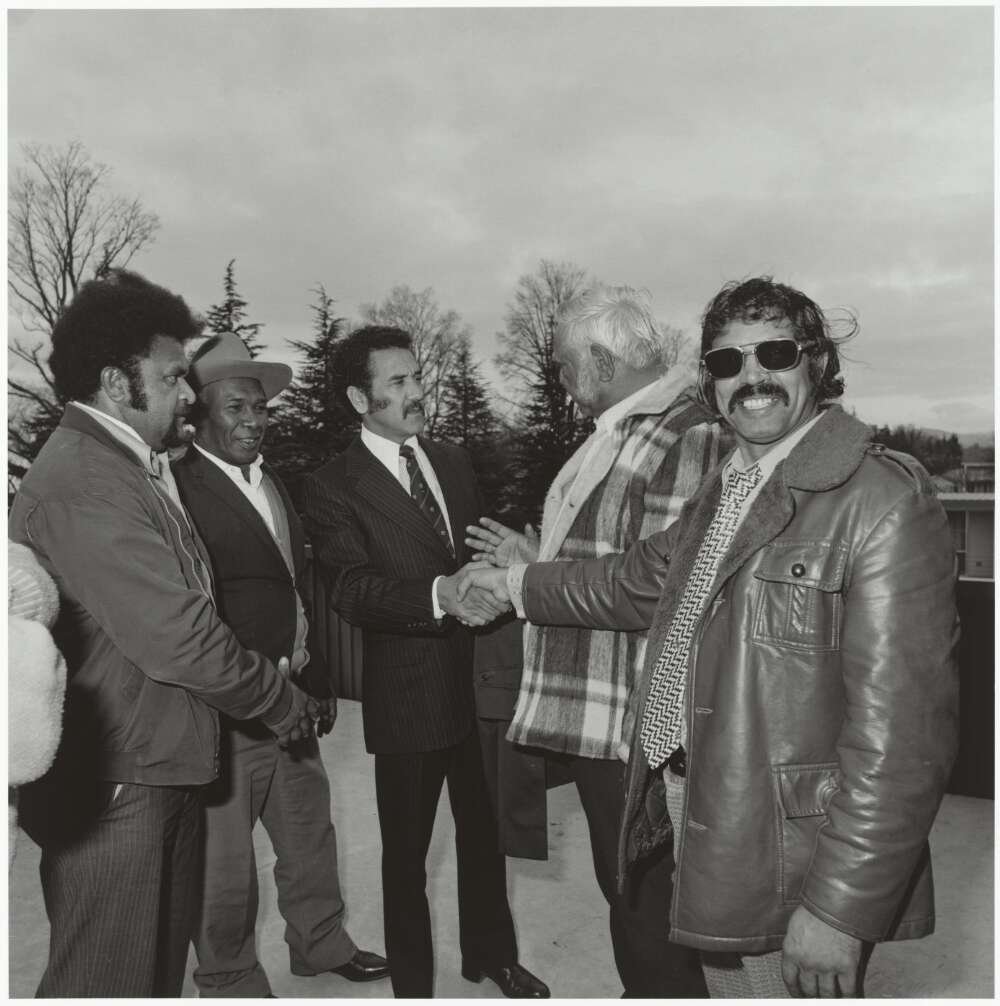

Following his graduation and his early activism efforts, Perkins continued championing Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander civil rights within organisations and in the federal public service. He held various roles within the Department of Aboriginal Affairs, where he started as a research officer and eventually became the Secretary for the Department. At that time, he was the first Aboriginal person to be the head of a federal department. During his time as Secretary he also remained a member of the Aboriginal Development Commission, serving as its Chairman from 1981–1984. As Secretary, he aimed to continue his goal of equipping Aboriginal people with the means to function in a society that had rejected them. He focused his efforts on the delivery of programs for Aboriginal communities and meeting with as many community members as possible. A quote from Peter Read's biography mentions that '[a]lmost every Aboriginal adult in Australia had heard of [Perkins]; the majority had met him'. Perkins was stood down as Secretary in 1984, due to allegations of mishandling of funds; allegations which were later disproven.

Mervyn Bishop (1945-), Charles Perkins Shaking Hands with Members of the National Aboriginal Congress, 1978, nla.cat-vn6853434

After his departure from the Department, Charles and his wife, Eileen, moved back to Alice Springs. This was an anxious move for them as many people in the community do not accept those who haven’t lived there their whole life. Despite this, the move back provided some positives. One achievement that gave Perkins a sense of fulfilment was being initiated into Arrernte law, which seemed to answer some of the bigger questions he had earlier on in life about himself and his people. However, due to ongoing kidney issues, the complexities of living out at Alice Springs became apparent, and Charles and Eileen moved back to Sydney.

After suffering from kidney problems for a large portion of his life, Perkins returned to the Dreaming in the year 2000. His commitment to Aboriginal Affairs gained him many admirers, but also some critics. While he was one of the more radical black leaders, there is no denying that his impact on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander affairs was paramount. In the words of Mandela: 'When a man has done what he considers to be his duty to his people and his country, he can rest in peace. I believe I have made that effort and that is, therefore, why I will sleep for the eternity.'