Many of us learn a musical instrument at some point in our lives. Some in childhood; others later on.

Whether music is always the ‘open door to popularity and happiness’, as this c.1950 Australian guide claims, is debatable, especially when wearing evening wear. But it can’t hurt, can it?

When learning the piano, few of us launch into playing J.S. Bach’s Art of Fugue or Sergei Rachmaninoff’s Second Piano Concerto without years of lessons. Many of us may learn in a graded way, often starting with some kind of introduction to the piano.

The National Library of Australia’s collections have some depth when it comes to these kinds of works. We not only hold the papers of stalwarts of twentieth-century Australian piano education, such as Miriam Hyde (1913–2005) and Dulcie Holland (1913–2000), and their many publications, but also earlier, printed exercises and guides to the piano. These collections have what may be surprising breadth.

This blog examines some of the Library's holdings, from the late eighteenth century to the twentieth century. In some instances, we hold both the early European printing, and numerous Australian editions, showing that these manuals had lasting relevance and impact over centuries. Interestingly, almost all of them claim to save both the teacher and student time, some being the equivalent of learning a language in 30 days – an appealing sales pitch.

First, what are we talking about when we talk about the modern piano?

The piano, short for pianoforte – meaning soft loud in Italian – is a stringed keyboard instrument on which sound is created through a hammer action. It evolved from earlier keyboard instruments though the inventor is widely credited as Bartolomeo Cristofori (1655–1731), keeper of instruments to the Medici ruler of Florence. He started making them in around 1700. Only three of his pianos survive today, including one at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

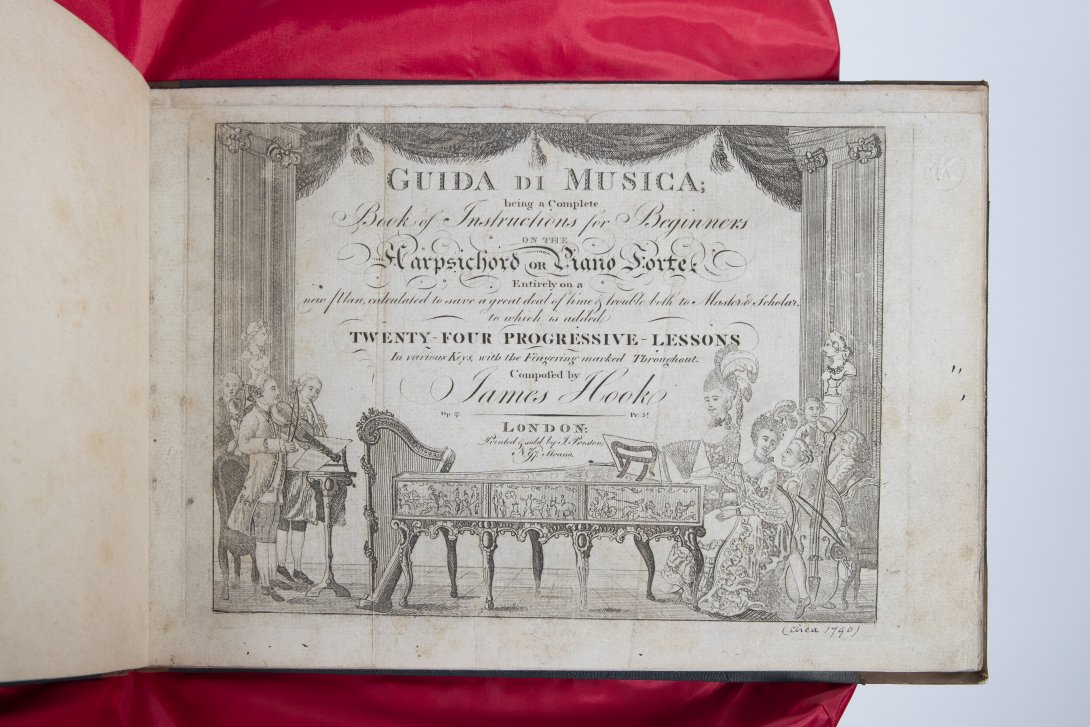

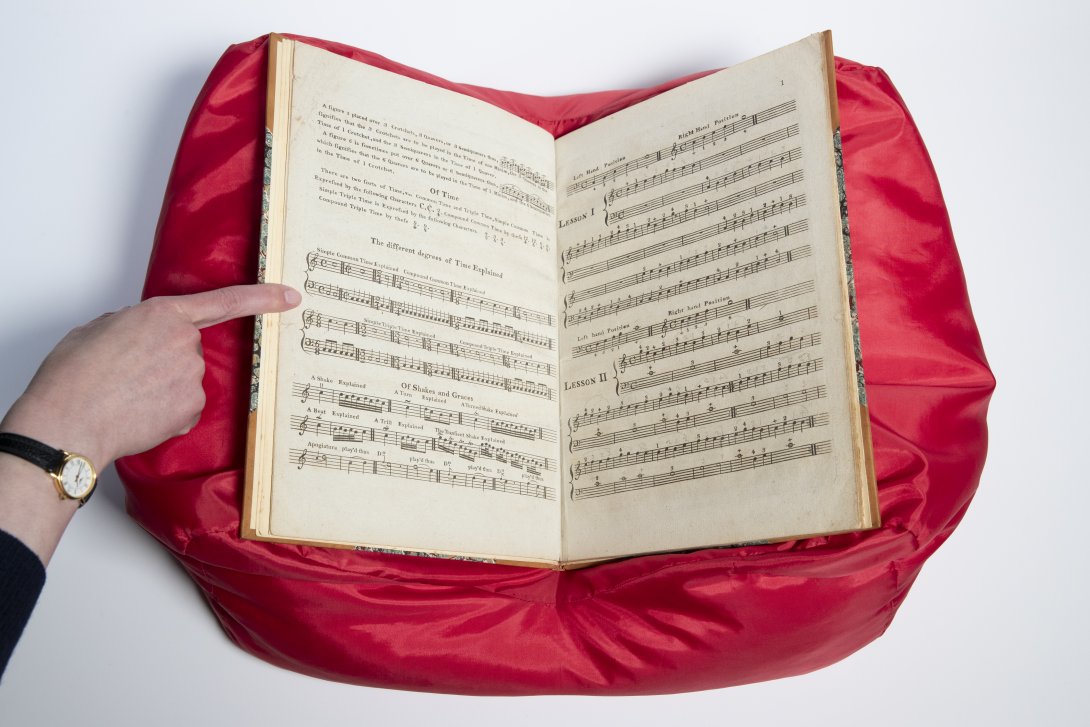

The earliest manual or book of exercises we are going to explore dates from decades later: James Hook’s Guida di Musica, of which we hold three copies.

Guida di Musica

James Hook was the organist and music director of London's Vauxhall Gardens – the pleasure garden south of the River Thames – between 1774 and 1820, for a staggering 46 years. These are the Gardens that feature in William Thackeray's novel Vanity Fair (1848). Hook was a prolific composer. He composed for the stage, including over 2,000 songs.

His Guida di Musica was well known, used and reprinted. Decades after the book's first printing, English novelist Jane Austen, herself a skilled pianist, mentions ‘Hook’s Lessons’ in a letter of 16 September 1813 to her sister Cassandra. Whether she ever owned a copy of Hook's Guida di Musica is unclear.

This is thought to be the first edition.

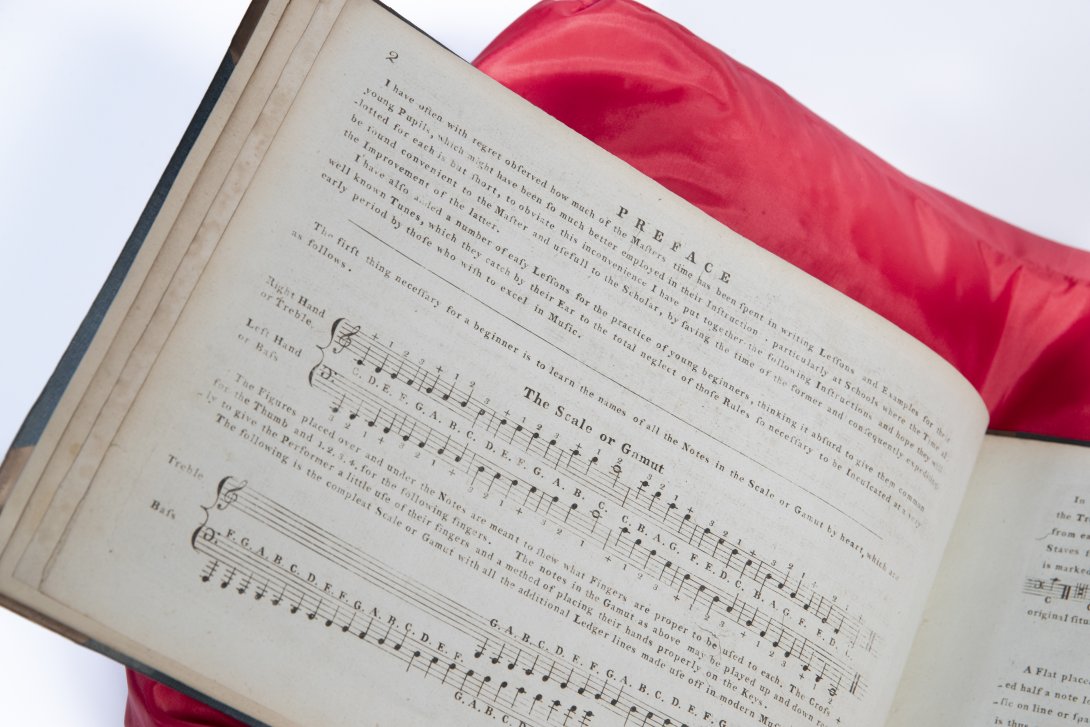

Hook explains why he has written the book in this preface:

I have often with regret observed how much of the Masters time has been spent in writing Lessons and Examples for their young Pupils, which might have been so much better employed in their Instruction—particularly at Schools where the Time allotted foreach is but short, to obviate the inconvenience I have put together the following Instructions and hope they will be found convenient to the Master and usefull [sic] to the Scholar, by saving the time of the former and consequently expediting the Improvement of the latter.

I have also added a number of easy Lessons for the practice of young beginners, thinking it absurd to give them common well known Tunes, which they catch by their Ear to the total neglect of those Rules so necessary to be Inculcated at a very early period by those who wish to excel in Music.

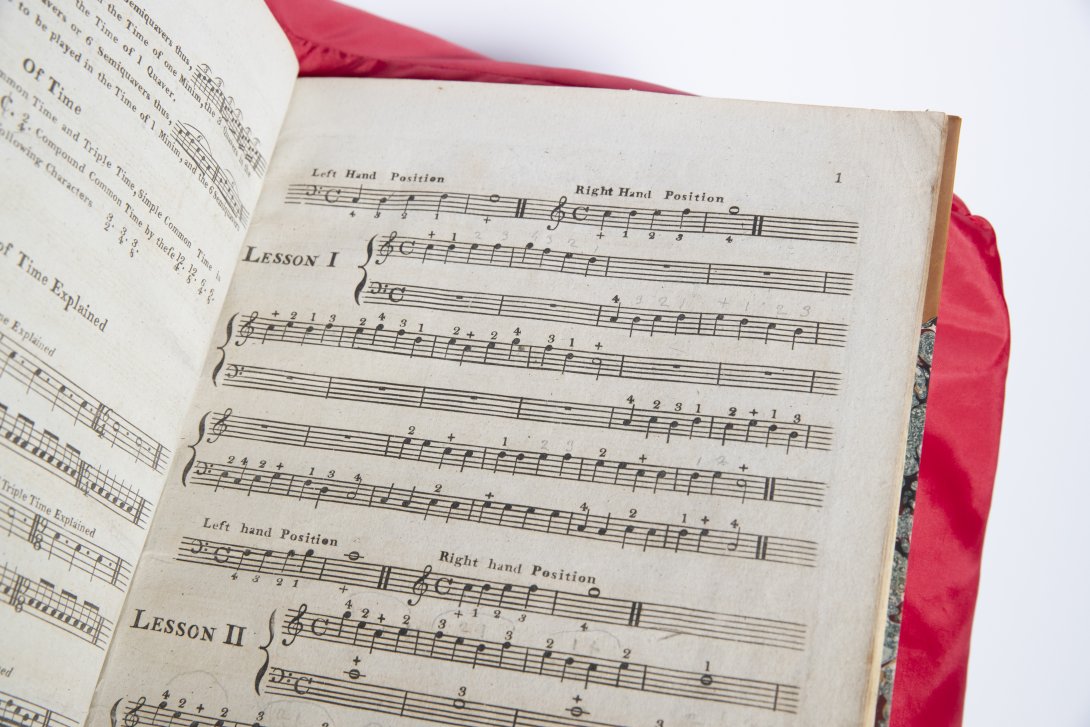

Then, he writes, above an image of the C-major scale for left and right hands: 'The first thing necessary for a beginner is to learn the names of all the Notes in the Scale or Gamut by heart'.

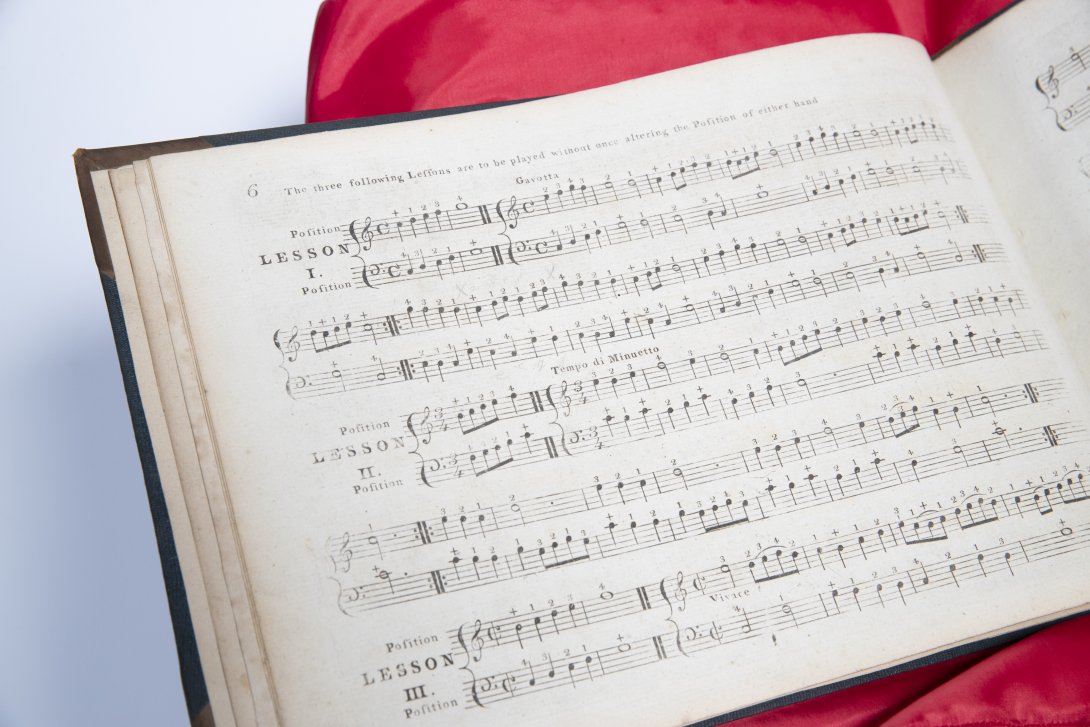

Address to the Scholar.

Be particularly careful to observe the fingering to the following Lessons, and never through carelessness or neglect make use of any other Fingers than are marked over the Notes, never attempt to play any Lesson quicker than you can read it.

As I have marked the fingering to all the following Lessons I shall not say any thing on that subject in this work, especially as I mean hereafter to give to the Public a Treatise on that particular branch of the Science, Illustrated with more than a Hundred examples.

Hook's Guida di Musica was published by John Preston, music seller, musical instrument maker, printer and publisher, who worked between 1773 and his death in 1798, much of that time at 97 Strand. A trade card dating to c.1783 is held by the British Museum. It makes it clear that Preston's specialty was as a 'Musical-Instrument Maker' in larger letters, then 'Original Inventor of the Machine for Tuning the Guittar with a Watch Key' in smaller letters. You can see one of his cellos is at the National Museum of American History. What is very interesting about Preston and the later history of his firm is that records survive showing copyright receipts, agreements and correspondence at the British Library. An article by Nancy A. Mace discusses them. The records show that Hook was one of Preston's most well-paid and frequently-published composers.

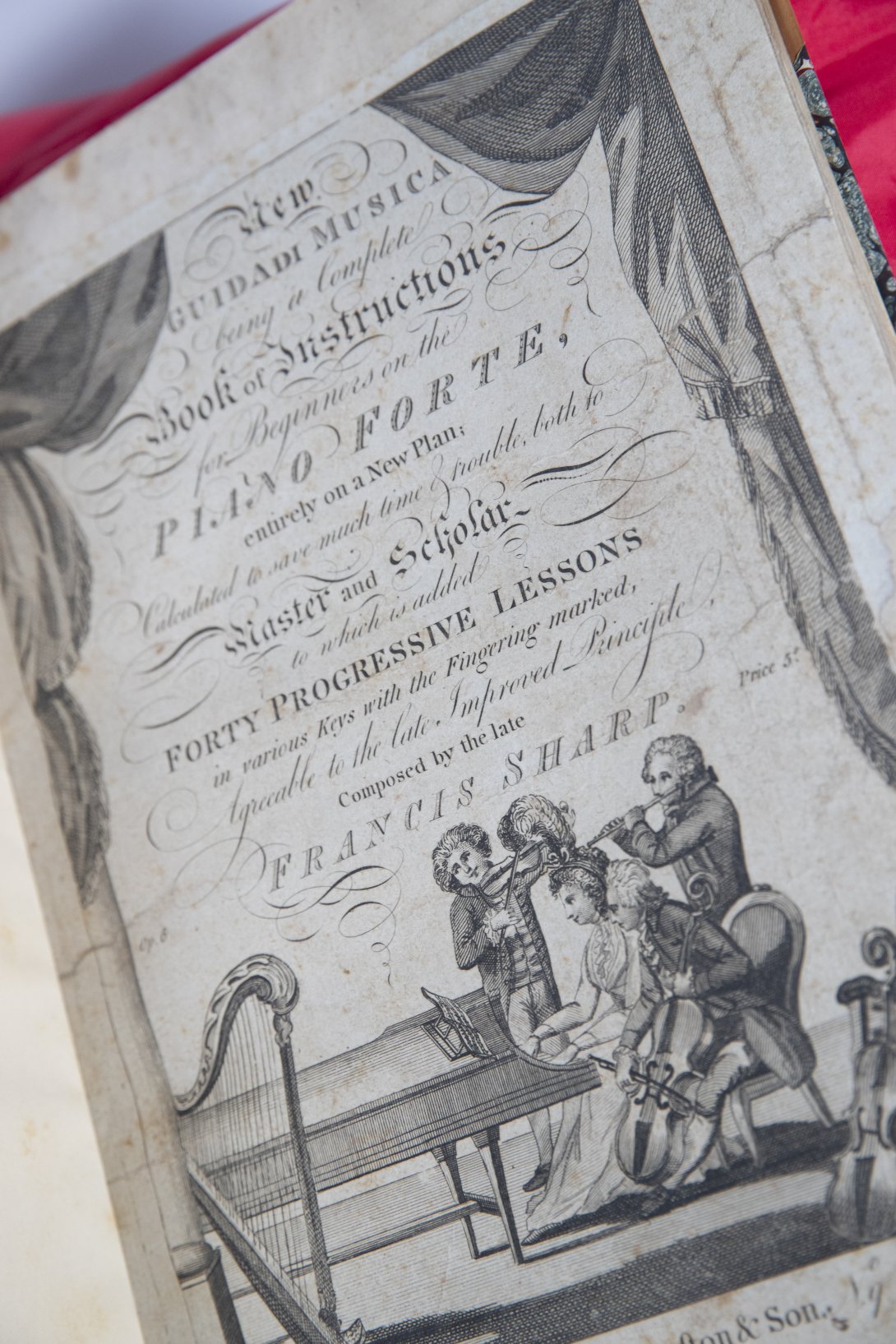

More Guida di Musica

Preston published another Guida di Musica in around 1797. This one was by Francis Sharp (1749–1795), who had studied under J.C. Bach (1735–1782), one of J.S. Bach's many children.

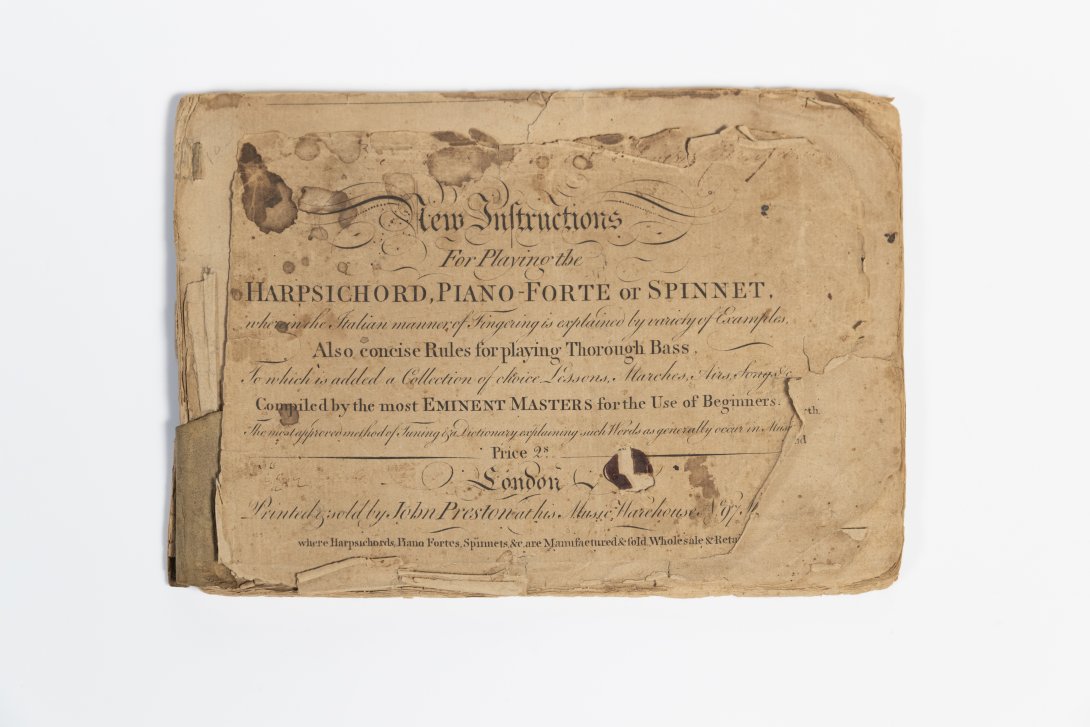

New Instructions

Used music often shows signs of wear and tear. This is no exception. It is unclear who wrote and composed it. Was it James Hook? It is possible – in his Guida di Musica, Hook refers to soon publishing a book on fingering. It was published by John Preston in the same year as the first Guida di Musica.

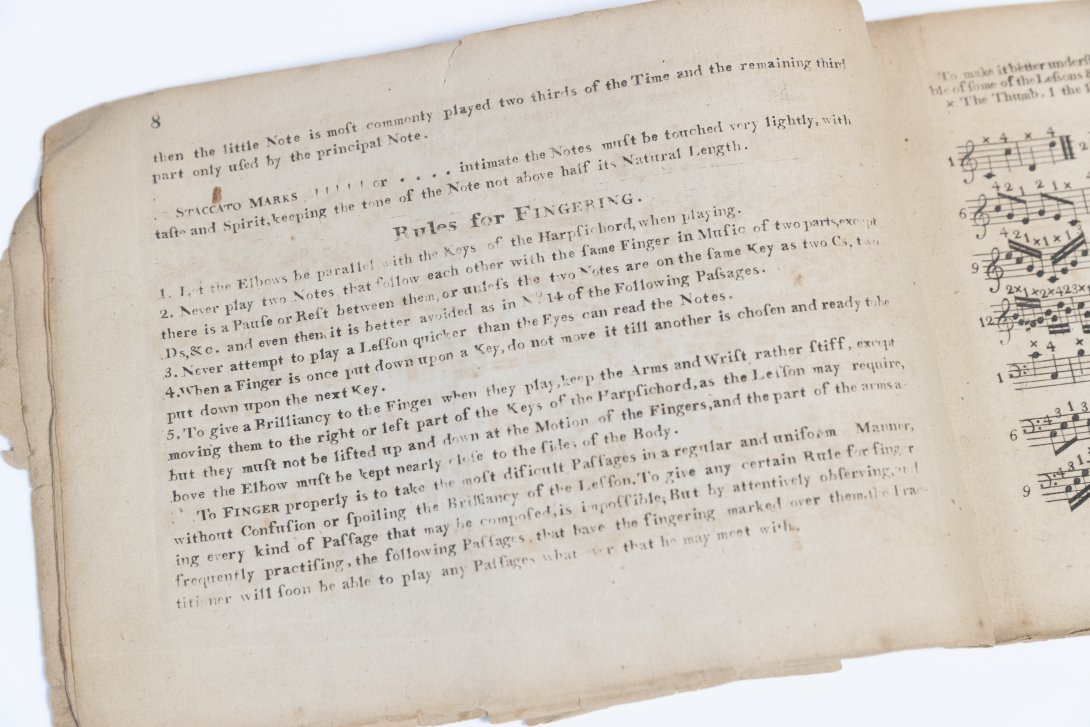

Rules for FINGERING

1. Let the Elbows be parallel with the Keys of the Harpsichord, when playing.

2. Never play two Notes that follow each other with the same Finger in Music of two parts, except there is a Pause or Rest between them, or unless the two Notes are on the same Key as two Cs, two Ds, &c. and even then, it is better avoided as in No. 14 of the Following Passages.

3. Never attempt to play a Lesson quicker than the Eyes can read the Notes.

4. When a Finger is once put down upon a Key, do not move it till another is chosen and ready to be put down upon the next Key.

5. To give a Brilliancy to the Finger when they play, keep the Arms and Wrist rather stiff ...

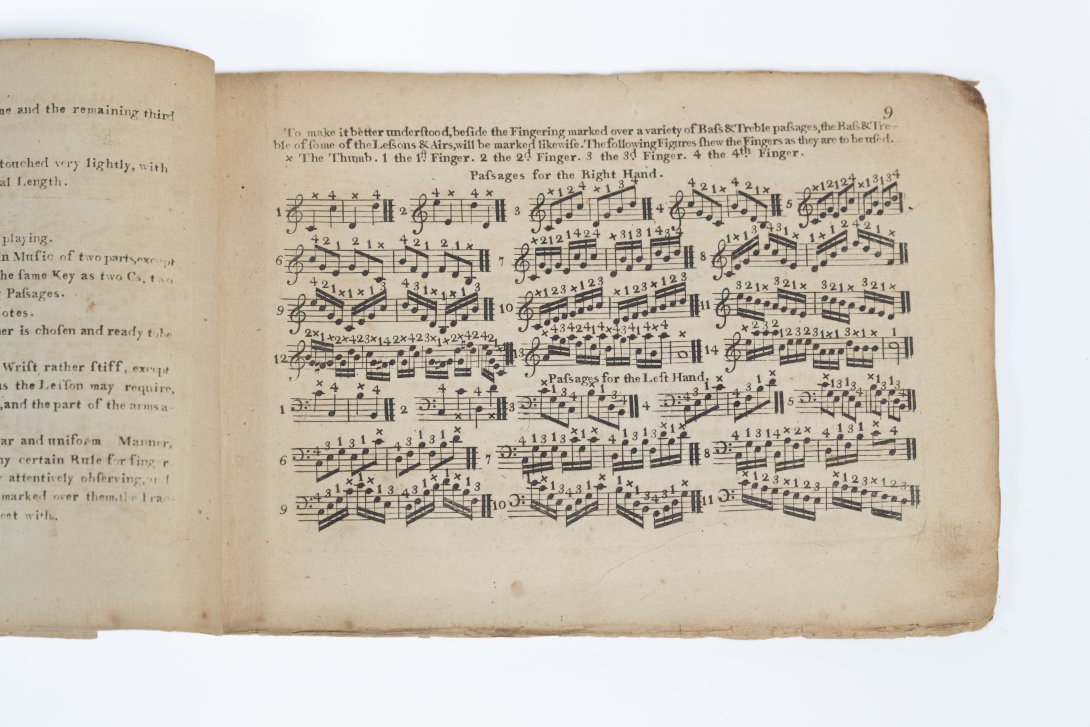

To FINGER properly is to take the most dificult [sic] Passages in a regular and uniform Manner, without Confusion or spoiling the Brilliancy of the Lesson. To give any certain Rule for fingering every kind of Passage that may be composed, is impossible. But by attentively observing and frequently practising, the following Passages, that have the fingering marked over them, the Practitioner will soon be able to play any Passages whatever that he may meet with.

Clementi's Introduction

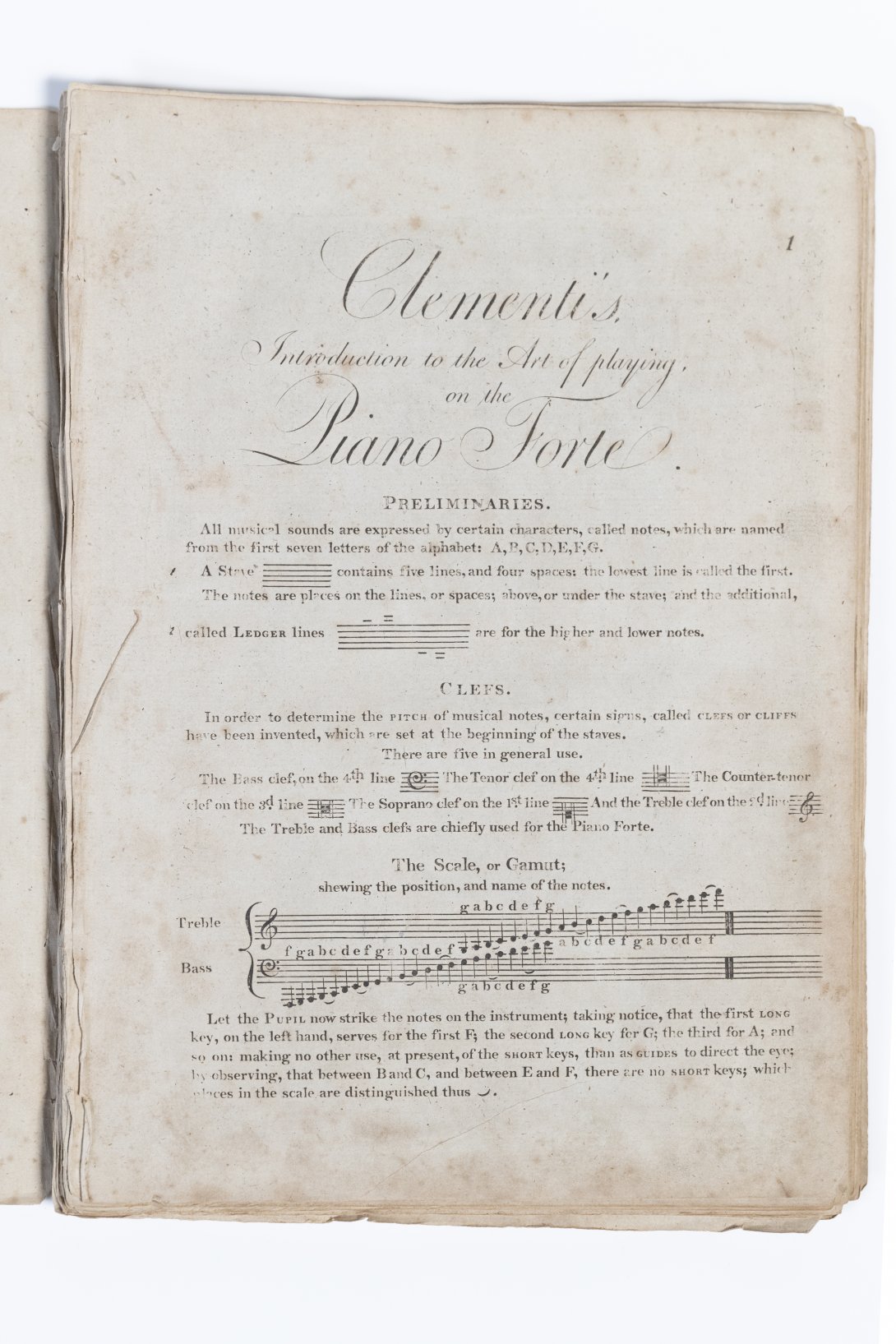

Italian-born English composer Muzio Clementi (1752–1832) was a man of many talents and interests. He composed, taught, was a publisher, made instruments and more. This is a first edition (though later issue) of one of his most successful educational works: Clementi’s Introduction to the Art of Playing on the Piano Forte Op. 42 (1801). There were 11 English editions, and translations in French, German, Spanish and Italian. A 1974 reprint of the first edition by Da Capo Press argued that its popularity and impact have been somewhat forgotten.

The first page, pictured above, starts from the very beginning, with definitions and illustrations of notes, staves, clefs and scales: ‘All musical sounds are expressed by certain characters, called notes, which are named from the first seven letters of the alphabet: A,B,C,D,E,F,G.’

A second part or supplement was more advanced.

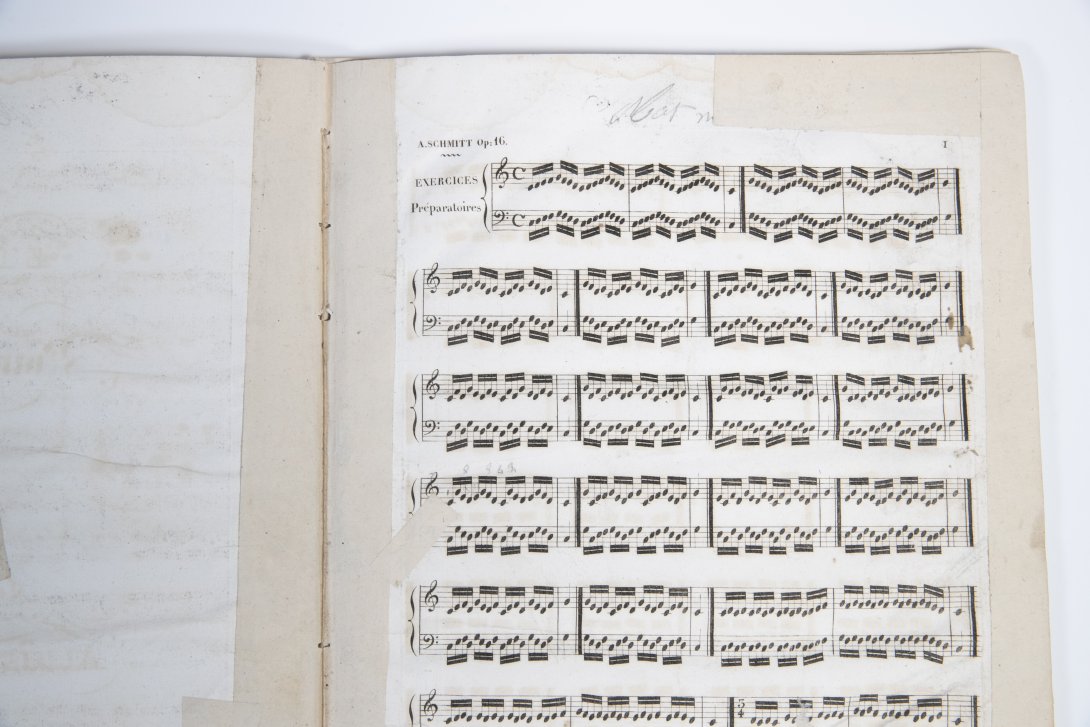

Schmitt's Five Finger Exercises

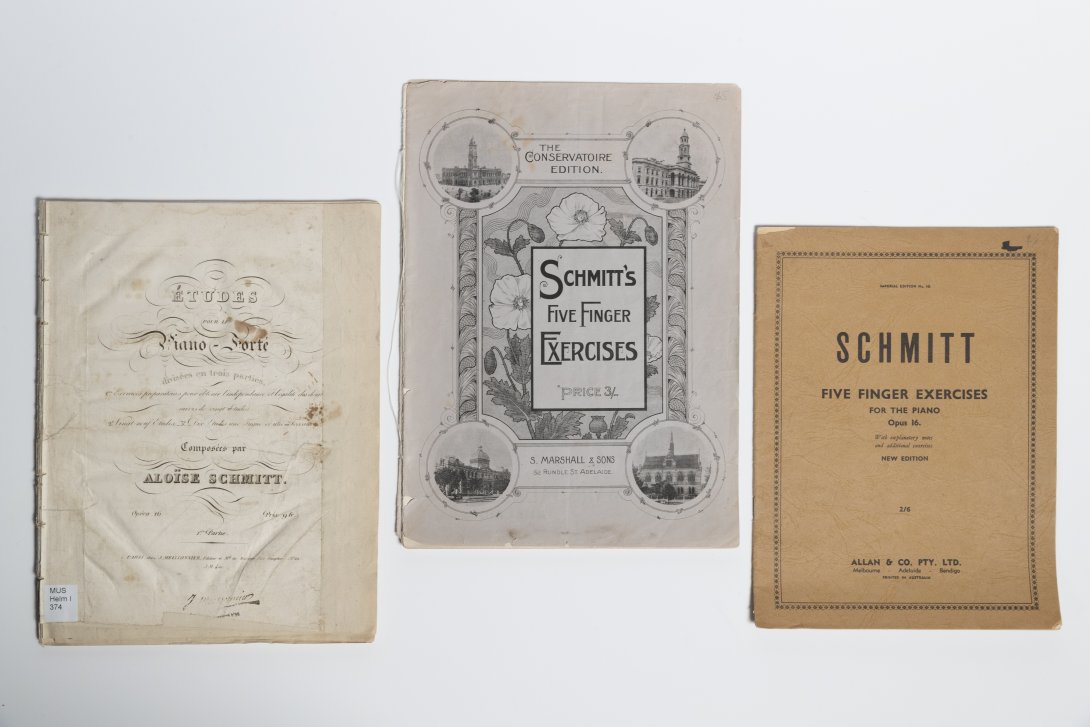

Aloys Schmitt's exercises are the ones I learned as a child. One of them rattles around my head to this day. So I was pleased to find that we hold numerous editions of Schmitt's exercises in our collection. Not only an early French edition, but also one published in Adelaide in the 1890s and several published in mid-twentieth century Australia by Allan & Co..

Schmitt's exercises were first published in Bonn in around 1819. Each exercise centres on the five fingers of each hand, offering a challenge for the brain and muscle memory of the fingers in their repetitivity. Our Palings edition published in 1880s Sydney has been digitised and is available for you to play.

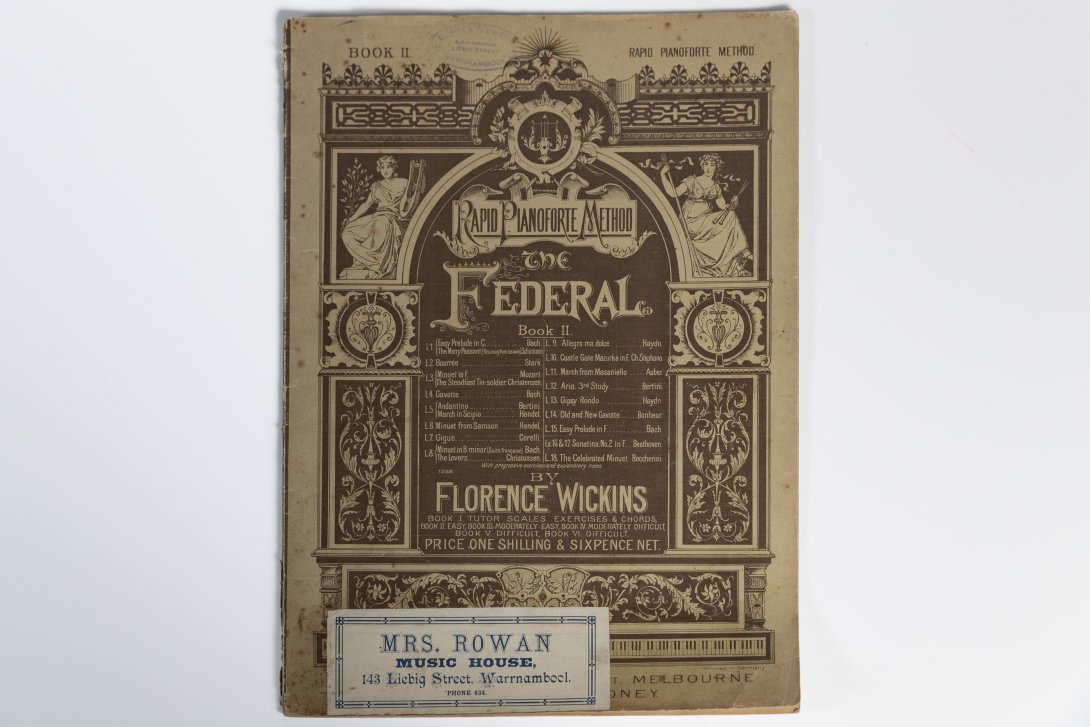

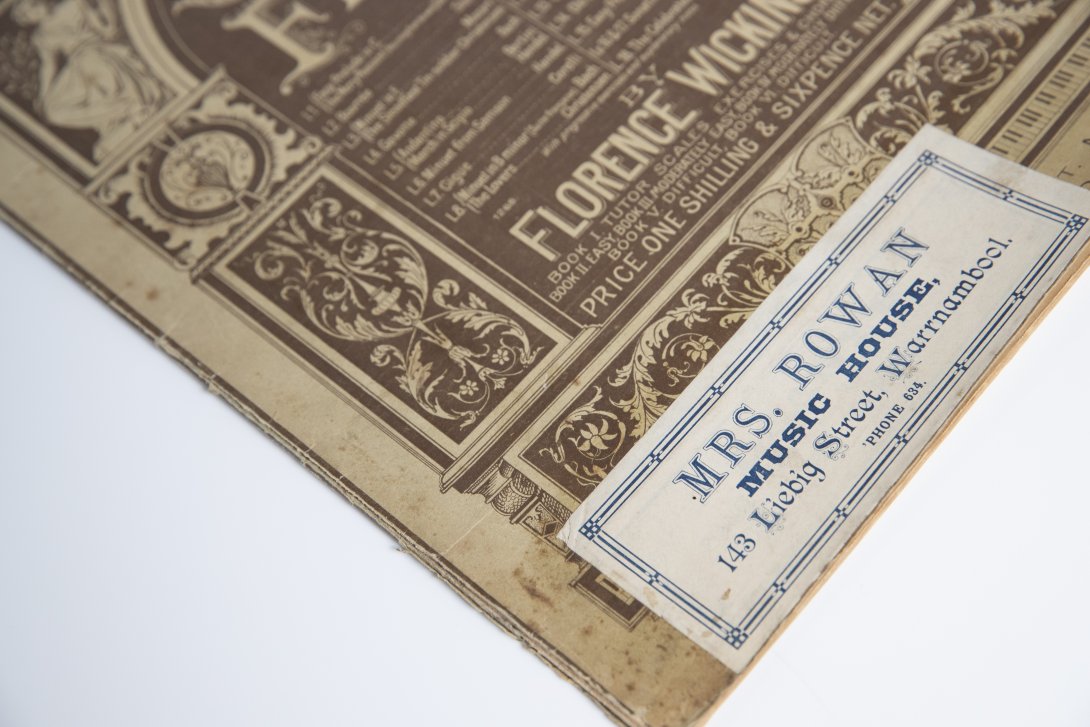

Florence Wickins

Florence Wickins' Federal Rapid Pianoforte Method was widely advertised around Australia in the 1890s and first decade of the 1900s. An article in the Brisbane newspaper The Week of Friday 10 November 1893 showers her method with praise:

Miss Wickins, by some happy method, has struck out a new line of pianoforte tutors. The work has the merit of originality and completeness, and there is no reason why her claim for rapidity of tuition – namely, the acquirement of moderate success in three months – should not be realised under a good teacher.

The Library's copy was sold at a Mrs Rowan's shop in Warrnambool

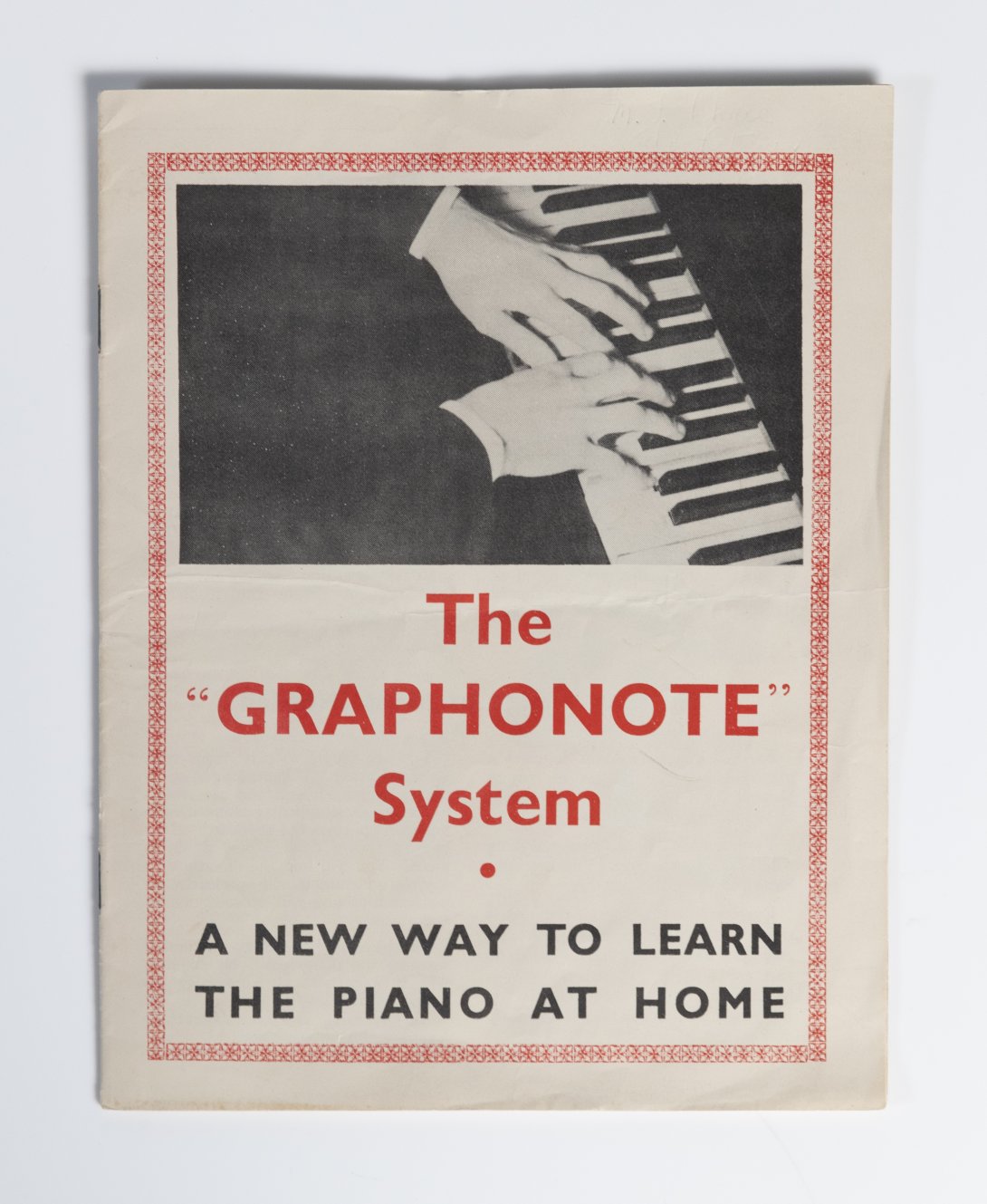

Australian systems and courses

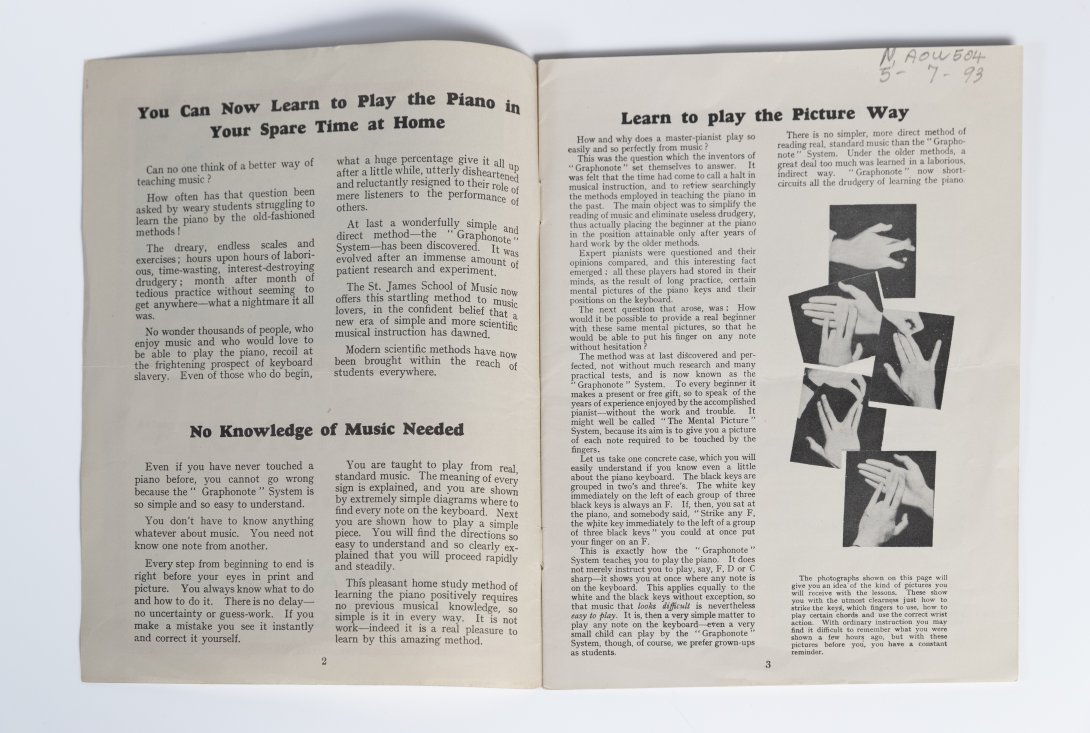

The Graphonote System's method originated in England, and uses pictures to show the student how to play.

This piano course was specifically for people who wanted to learn to play jazz piano. Advertised widely in newspapers, it was a mail-order course that people could order. The Library holds numerous parts of this course.

May Willis

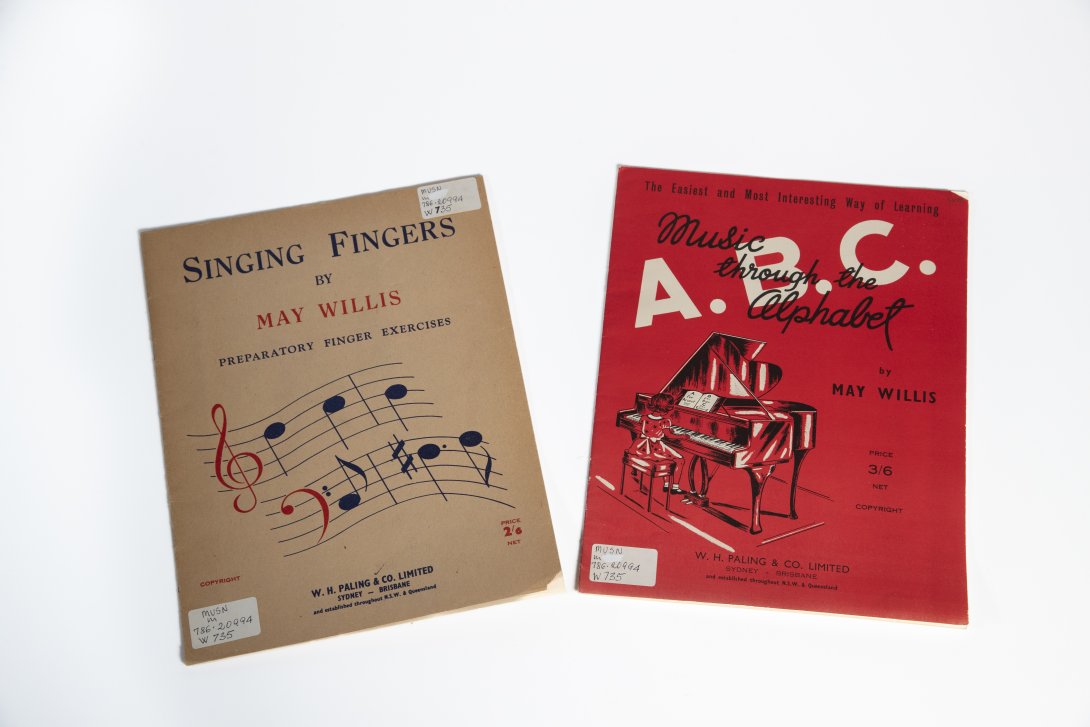

Perhaps best known for her Magic Land of Music (1934), May Willis composed piano works for beginners. These two works approach playing the piano from different angles – singing and through the alphabet.

All our music is available for you to call up to our Special Collections Reading Room, where you can have a play on our electronic keyboard. Go on! Start learning today. These guides can save you time, but I'm afraid their guarantees have long since expired. And if the piano isn't your thing, we have many 'how to play' guides for many other instruments.

Dr Susannah Helman is Rare Books and Music Curator, National Library of Australia