Due to scheduled maintenance, the National Library’s online services will be unavailable between 8pm on Saturday 7 December and 11am on Sunday 8 December (AEDT). Find out more.

By Katherine Kovacic, author of the NLA Publications book Australia’s Dogs.

A few years ago, I began scouring the National Library’s collections for pictures of dogs. I was researching aspects of Australian art history, and at first my aim was to explore what the Library held in the way of paintings of dogs. And then, well…

As a veterinarian turned art historian, I’ve always been drawn to animals – particularly dogs – in art. What makes dogs so interesting to me is the way they interact with humans in paintings, the way they have been depicted in portraits (either alone or with their human companion) and the way artists use dogs to convey meaning about the action within a painting. Essentially, I’m fascinated by the history of dogs and the human-canine bond in art. And so as I was researching paintings, more and more I found myself looking at photographs, requesting them from storage, trawling through digital files and, very often, trying to find out more about the people and canines I was looking at: just who were these dogs and their humans, and what was their story?

Photography for all (creatures)

In the nineteenth century, the advent and rapid development of photography meant that portraits were no longer just for the wealthy. Instead of sitting for an artist, it was now possible to visit a photographer’s studio and have a portrait made. It was this type of formal photograph in the Library’s collections that first drew my attention. Here was that same dynamic between dog and person but without the artistic licence of a painter. There could be no tweaking the position of a person’s hand or subtle altering of a facial expression, just the purity of the relationship, captured in startling clarity.

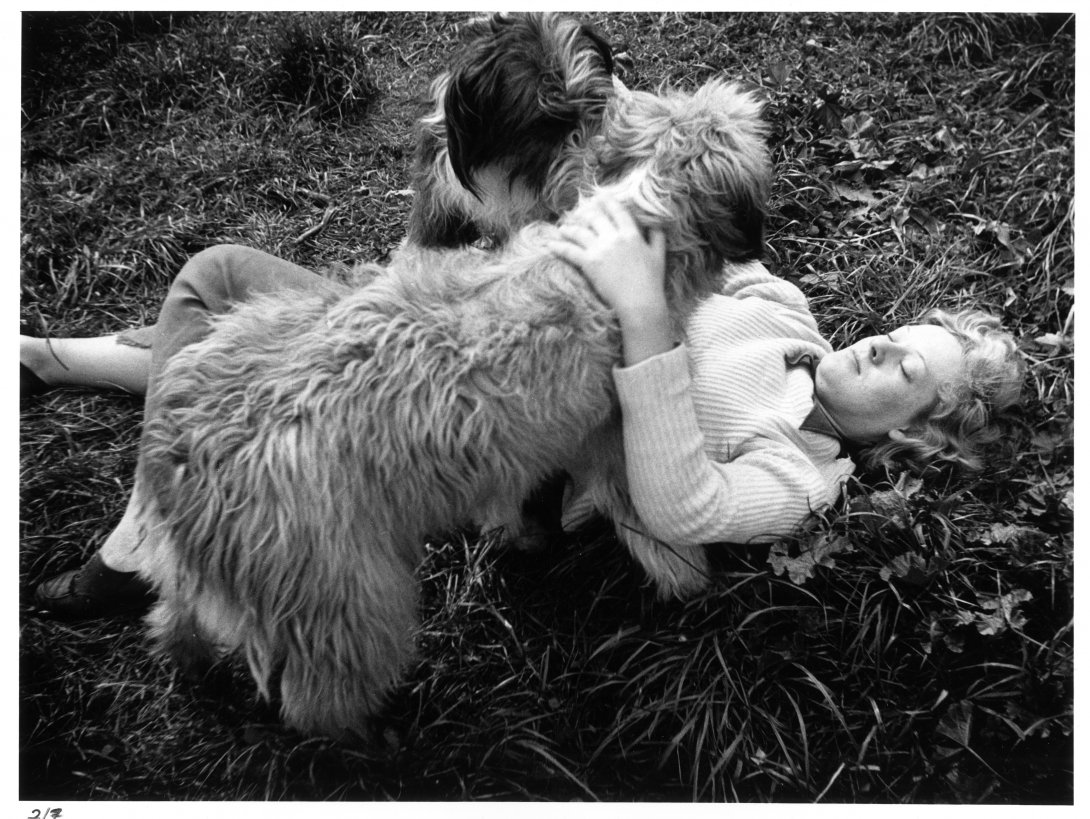

I confess, I went down a rabbit hole, because as the technology became more sophisticated, cameras moved from the realm of the professional to the amateur. The snapshot was born and with it came spontaneity and the messiness and fun of everyday life with dogs.

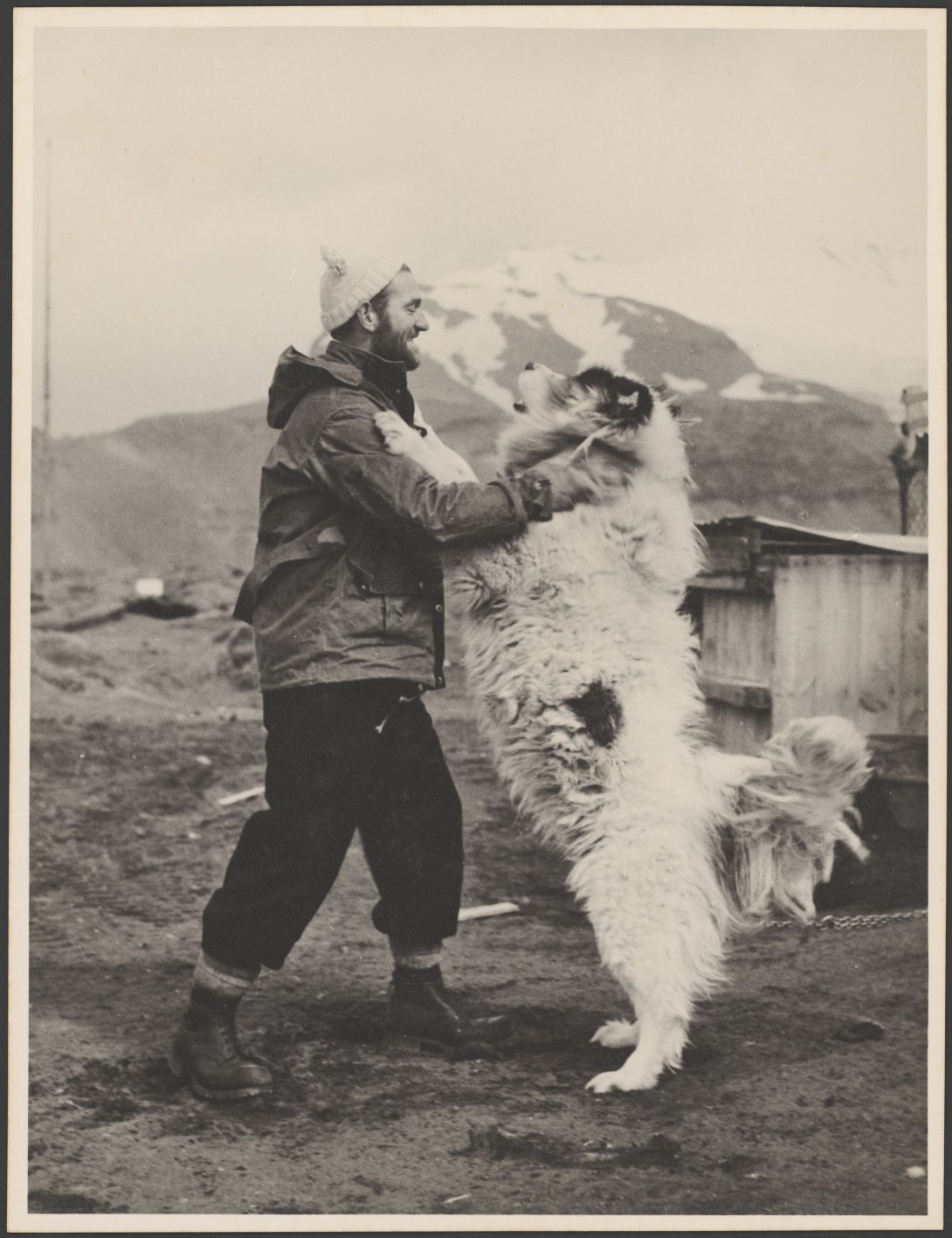

There is something special about having a dog in a picture. If the canine is the main subject, it tells the audience about his importance; if he is part of a group, the humans are often more informal because of his presence, their defences drop and we see more of the personality behind the pose. And regardless of what was intended, someone looking at these pictures today can also study the background, the fashions and all those other myriad details that reveal so much about the evolution of Australian society and the country itself.

A unique bond

For me, it was also both fascinating and educational to look at the varying popularity of different dog breeds, the changes – generally not for the better – in the anatomy of certain breeds and to see the universal popularity of bitzers. But I also found that looking at these photographs was not only interesting, it was uplifting; I was smiling – and sometimes laughing – all the time.

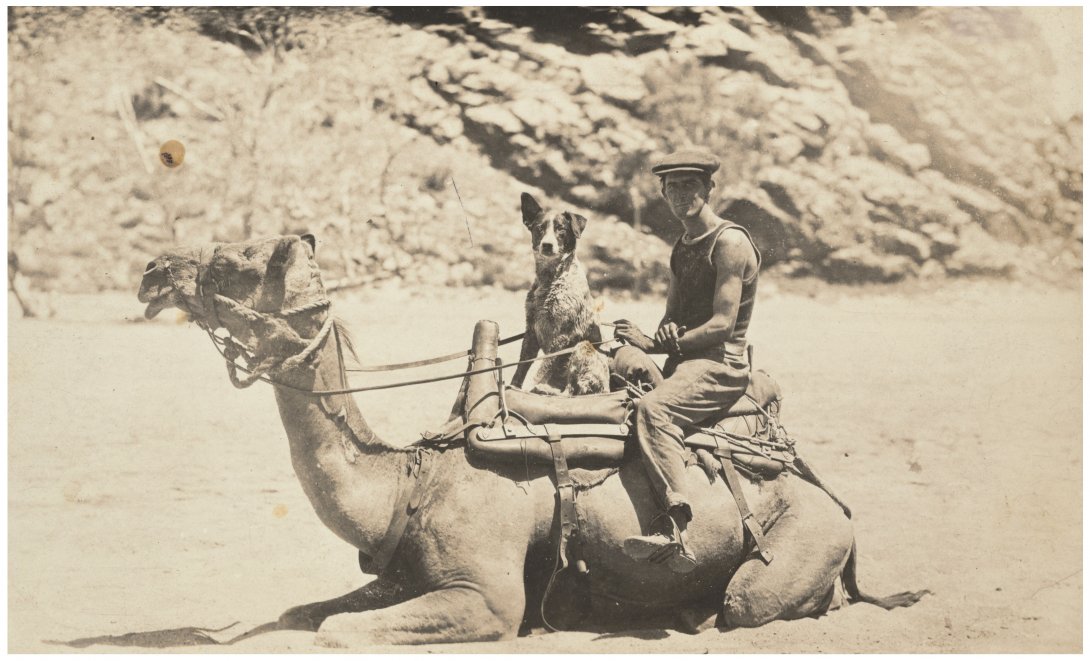

I discovered so many wonderful dogs, and also people. One of those people was Francis Birtles, an adventurer who crisscrossed outback Australia on multiple offroad journeys during the 1920s and 1930s. Birtles had excellent bushcraft, but he was also a skilled promoter of his exploits. That meant writing extensively for newspapers and periodicals, as well as taking plenty of photographs (or even filming) his trips. The Library holds an extensive collection of these photographs and they show not only some of the most remote corners of our country, they also include the dogs that accompanied Birtles on his adventures. Birtles’ dogs were popular with the public and part of the profile he presented, but in teasing out some of their stories I also found this tough outdoorsman was a softie when it came to his four-footed mates. He loved his dogs deeply, and those dogs were part of his emotional support system in times of distress.

Pieces of the puzzle

There are so many magical pictures that didn’t make the final cut. I made successive passes through the long list, covering the floor with printouts, whittling the numbers down. As we drew closer to the final version of Australia’s Dogs, the team at NLA Publishing and I had numerous discussions, and during one of those it was decided to include a handful of artworks and illustrations to fill in some of the early visual history of dogs in Australia. It was a tough decision, because that also meant a few more of my favourite photos were consigned to the ‘no’ pile: a laughing girl running on Bondi Beach in 1925, her small, fluffy black and white dog tugging at the towel that streamed behind her; a tiny terrier, the mascot of the 1st Australian Light Horse, nipping a soldier’s ankle; a dog sitting in the shade of a car, the only relief from the blazing sun in a barren outback landscape.

In many ways, there was no need for text – these wonderful pictures speak for themselves. But there was also a lot of incredible history and stories to explore, and with that comes greater understanding of what these dogs have brought to Australian life. Some of my most exciting research moments came when I was able to discover dogs’ names, restoring that part of their personality and life to the historical records.

Working on Australia’s Dogs has been a delightful experience, and I hope the book brings a bit of doggy joy to everyone who flips through the pages.