Due to scheduled maintenance, the National Library’s online services will be unavailable between 8pm on Saturday 7 December and 11am on Sunday 8 December (AEDT). Find out more.

by Peter Valentine, author of NLA Publishing title World Heritage Sites of Australia

In 2008, when I was first appointed to the Australian Heritage Council as a ‘natural heritage’ expert, the first place on the National Heritage List was Budj Bim. I knew nothing about it but I quickly became aware of its remarkable qualities. Later, in 2012, with colleagues from the IUCN World Commission on Protected Areas, I was part of a National Symposium on Australia’s World Heritage places. While there, I spoke with Denis Rose, who made the case on why Budj Bim should be nominated by Australia for UNESCO’s World Heritage List, and what an amazing story it was.

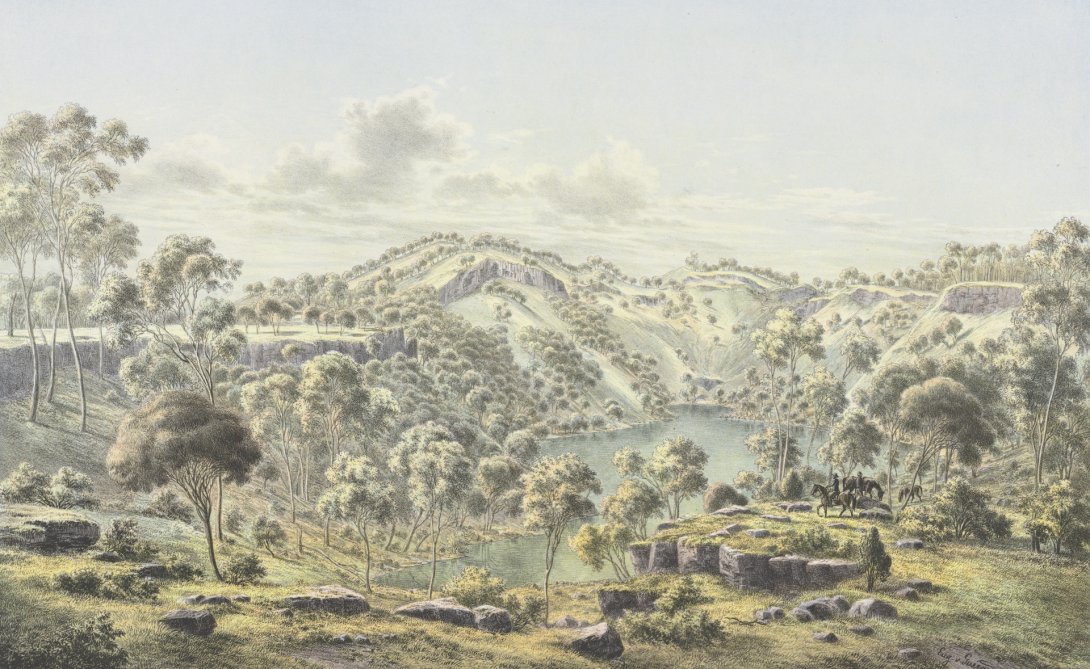

Try and imagine south-western Victoria, near present day Lake Condah west of MacArthur, some 30,000 years ago. Gunditjmara ancestors experienced the development of a volcano and its associated lava flows as the lava spread across the landscape, filling river channels and blocking water flows. To them, it was the actions of the ancestral creation being Budj Bim revealing himself in the landscape, and in the process, extensive swamps and lakes were formed. These provided new opportunities for people to develop distinctly different lifestyles.

By 6,500 years ago, the Gunditjmara had developed the landscape into an amazing network of weirs, ponds, channels, and connected waterways that supported their intensive kooyang (eel) farming. The adult short-finned eels (Anguilla australis) migrate down the rivers into the ocean and head across the Pacific Ocean to breed, including to the seas around Lord Howe Island (another World Heritage Area). Later the young elvers return to these same rivers and head upstream where they live and grow for many years before repeating the cycle.

The complex technology of the Gunditjmara network allowed them to harvest enough eels not only for immediate consumption but also for smoking (which preserved them) and trade. Such intensive aquaculture enabled permanent settlement, and archaeologists have documented a settled society with villages of stone huts built from the basalt.

Not surprisingly, this astonishing site was inscribed as the Budj Bim Cultural Landscape World Heritage Area in 2019. The nomination followed Budj Bim’s previous inscription as the very first site on the Australian National Heritage List in a process led by the Gunditjmara community. The area is partly contained within Budj Bim National Park. Originally called Mt Eccles, that name itself was a drafting error from explorer Major Mitchell’s original Mt Eeles and had no significance. The renaming by the Victorian Government to celebrate the ancestral creation being of the Gunditjmara seems highly appropriate.

Fortunately for me, while I was preparing material for the second edition of World Heritage Sites of Australia, I met with the Gunditjmara community and was invited to visit their wonderful World Heritage Site. I was shown the site’s important places by some of the wonderful rangers and met with CEO Erin Rose, daughter of Denis. The new visitor centre enabled an even greater appreciation of the aquaculture system still functioning today. I also met some kooyangs. Walking over the ancient lava flows and seeing for myself the stone-walled house remains gave life to the stories about amazing Gunditjmara Culture and heritage.

During my second term on the Australian Heritage Council we were asked by the Minister to provide an assessment on whether the Murujuga National Park—and the amazing rock engravings (petroglyphs)—would have potential to achieve World Heritage. I was privileged to go with my fellow Council members to help conduct the assessment and what we learned was highly convincing.

The place has exceptional qualities, indeed the only place in which 50,000 years of cultural artistry records the lives of humans at one magnificent site. At least a million petroglyphs show all manner of species and indicate human activity over a great time span, each engraved in hard rock within a stunning landscape. While the Council reported their confidence the site met the necessary criteria for World Heritage Listing, it was disappointing that no nomination was made by the Government of the day. Now, in an exciting move, Murujuga has been nominated and is in the process of being assessed by UNESCO as a potential addition to the World Heritage list. That outcome is some time away, due to the complex procedures involved, but I am confident that Murujuga will become a World Heritage Site.

Despite this nomination, the official Australian Tentative List—those places that Australia intends to nominate for World Heritage listing—remains highly impoverished compared to most other comparable countries. In 2021, another site was added, bringing our tentative list to four. This was the Flinders Range of South Australia. What a remarkable potential site! Many Australians know the Flinders Ranges as an extremely beautiful landscape with rugged geology, colourful rocks and fabulous gum trees. But hidden within the rocks is the story of the dawn of animal life on Earth.

The geological sequences incorporate fossils that record the first attempts at animal life and the emergence of different forms of life over a 350-million-year period. This succession includes life from microbial stromatolites to early primitive multicellular life all the way to the advent of animals (as exemplified by the remarkable Ediacaran Biota). The evolution of skeletons, limbs, eyes, predation and other features provide a direct link to modern animal life, including our own. I am delighted to see this area - one of my favourites - added to our tentative list and hope to see a formal nomination soon.

This does raise a question: how many more World Heritage sites might we see from Australia?

In the penultimate chapter of the book, there is a discussion of potential future World Heritage sites in Australia, drawing attention to some worthy places that could add at least another 20 sites to our list. Cape York Peninsula in Queensland; the Southwest Floristic Province and the Kimberley region in Western Australia; the Australian Alps across NSW, Victoria and the ACT; the Nullarbor Plain in South Australia; the Australian Antarctic Territory; and a number of potential desert sites across the nation. Many of these have already had much formal work done on their significance and simply await official nomination.

As First Nations people regain access to their country, we might expect many additional elements added to the story of Australian World Heritage.

Having spent 30 years working on world heritage in Australia and overseas, the idea of writing a book on world heritage seemed obvious. On reflection, I was able to identify my most salient motive: I wanted more people to understand Australia’s significance on the global stage. I envisaged an opportunity for everyone to celebrate the wonders of these exceptional places.

The partnership with the National Library of Australia publishing team was a perfect outcome that gave me access to some amazing material. It was agreed that each site would have a complete chapter to ensure sufficient space to outline the international significance of the site and provide a good spread of illustrations and stories to capture the essence of each. In many cases, sites have been nominated through community action and sometimes involved conflict, so it was felt important to discuss the pathway to successful listing for each one. This enabled recognition of the roles of individuals and communities in achieving the long-term protection of these places.

In this second edition the strong role of Indigenous Peoples in both identification and management has emerged. I am grateful to acknowledge these links to Country becoming much more direct and explicit.

Despite the clear threats to some of our astonishing World Heritage Sites, it is still the case that they capture some of the most exceptional natural and cultural heritage on the planet and continue to form the basis of significant visitation. My hope is that readers will become even better connected to these wonders and perhaps take steps to support ongoing protection and better management.