The eighteenth century was a time of extraordinary change in Europe, of political and social revolution, increasing scientific endeavour and reflection on what it is to be human.

And by the end of the eighteenth century, more European women than ever before saw their work in print. Women still had few rights, but the conversation was changing. Their works were being read and having influence, whether it be on readers or in the fight for women's rights.

This blog, the second in a two-part series, introduces some of the Library's rare books written by women, and published in the 18th century.

The books span works of reference, novels, poetry and polemic. Their authors led extraordinary lives of achievement and challenges, celebrity and withdrawal from the world, in some cases all of these. Some have received much more attention in recent decades than in the past, thanks to a refocused lens on women writers. This blog explores each writer, her book's publication history if known, and previous owners of our copies. The books differ in one major and exciting way from books we met in the first blog in this series: Great female writers of centuries past. Most were owned and inscribed by women. And these women can be traced.

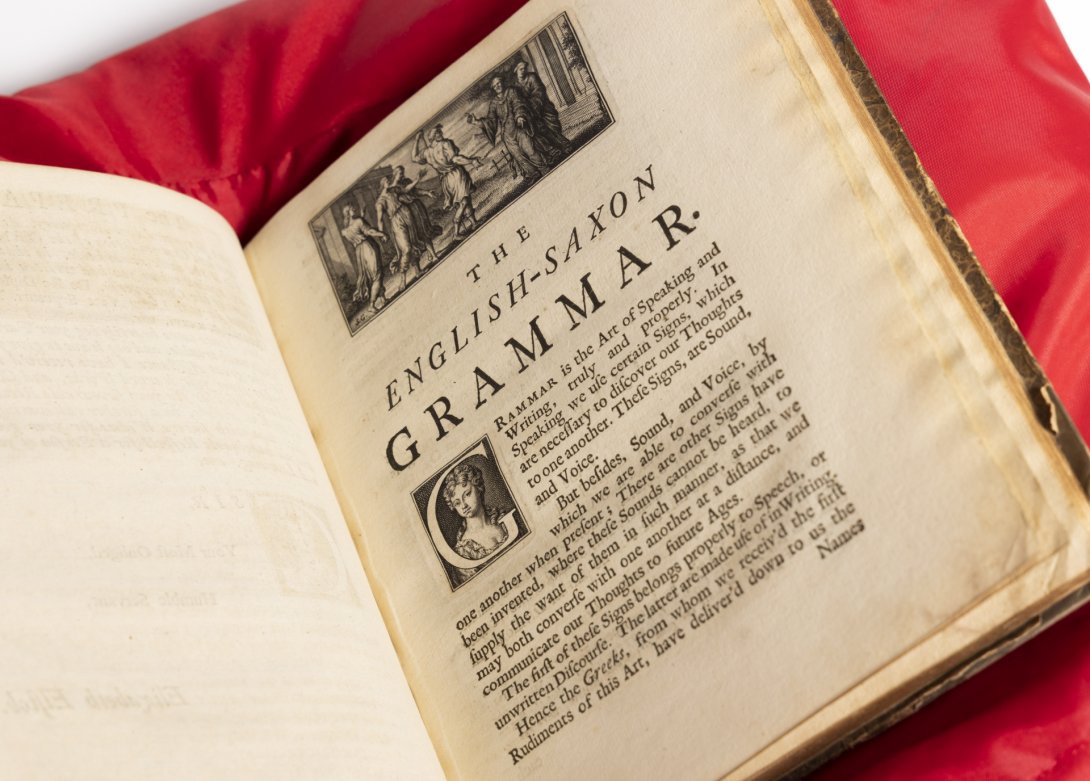

Elizabeth Elstob

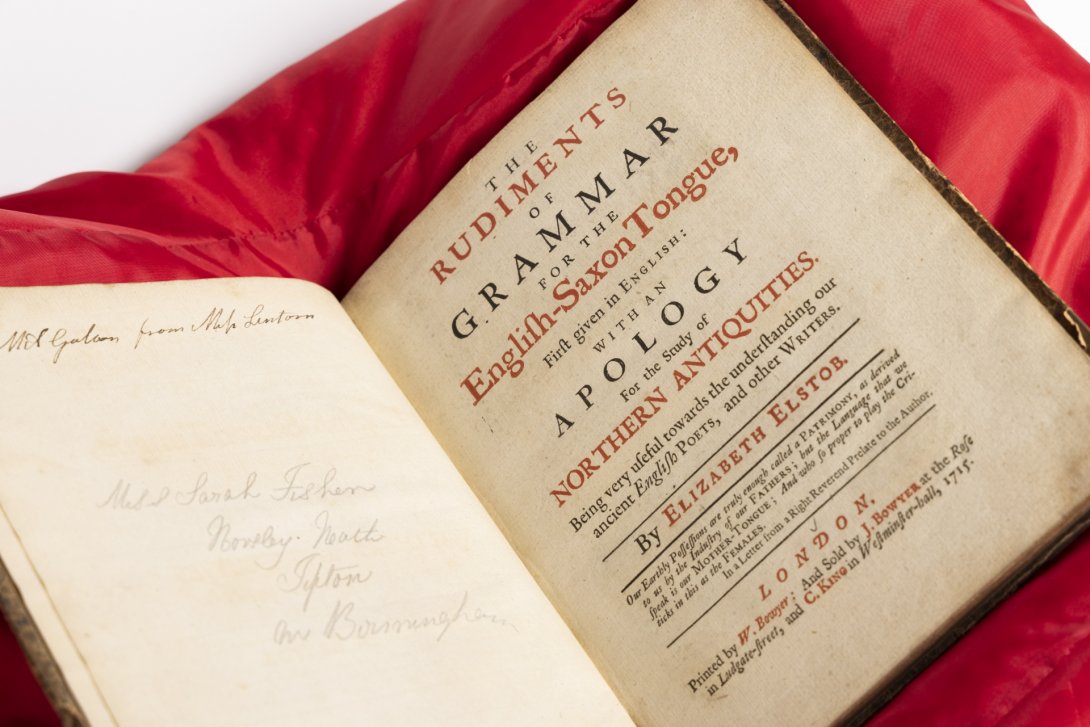

In 1715, this slender book was printed by William Bowyer. Written by Elizabeth Elstob (1683–1756), The Rudiments of Grammar for the English-Saxon Tongue is the first grammar of Old English written in English. The Library holds two first editions, which are the only copies in public library collections in Australia.

Elstob's work has been increasingly studied and recognised. She was the child of a wealthy merchant father from Newcastle upon Tyne, in the north of England, who invested in all his children's education. But Elizabeth's parents died young, and after some time with an uncle doubtful about the value of women's education, she went to live with her elder brother William, a scholarly clergyman with interests in Old English. She ran his household, and they worked together and separately on several books. Elizabeth had a working knowledge of multiple ancient and modern languages: her first book was a translation of work by French writer Madame de Scudéry. No doubt through her brother and her own determination and scholarly connections, she had access to excellent library collections. Tragically, her brother died in 1715 and she was saddled with debt incurred by their joint publications. She escaped by living and teaching under a pseudonym. She never published again. From the 1730s, she was a tutor in the household of the Duke of Portland, where she died in service in 1756.

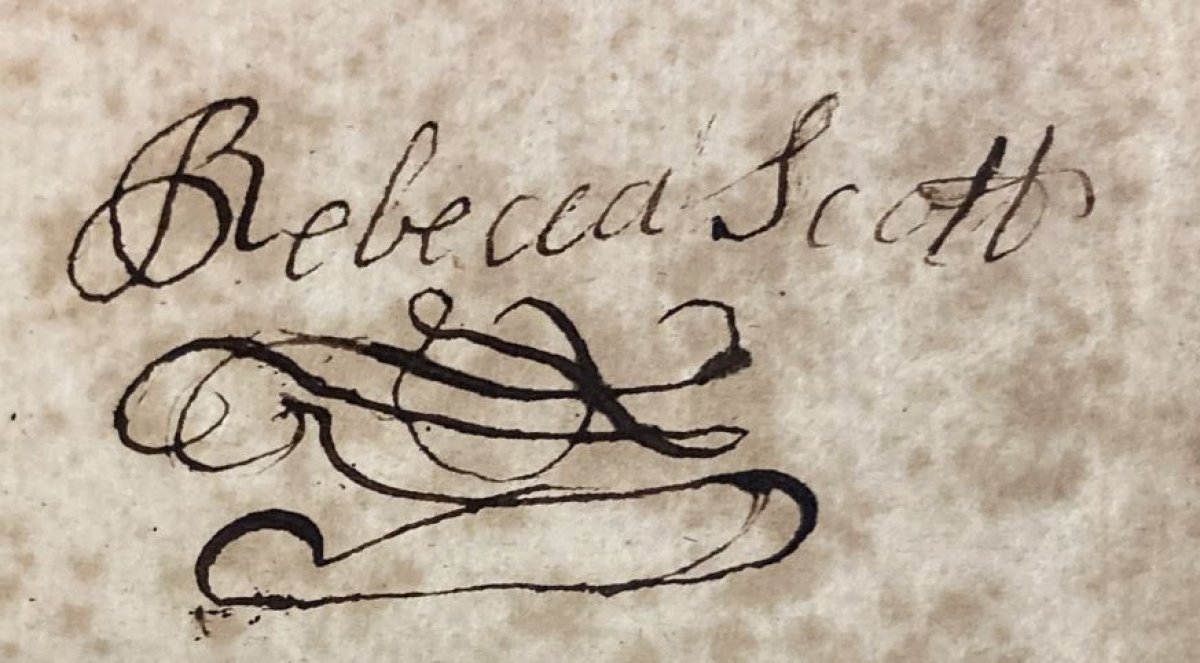

One of our books was owned by several women in its history, before becoming part of the Clifford Collection, the English country house library acquired by the Library in 1963. Many of the books in the Clifford Collection were plainly acquired new, and at the time of publication. This book suggests that the collection also absorbed books on the way. The earliest known owner appears to be Miss Sarah Fisher, from Horseley Heath, Tipton in Staffordshire (near Birmingham, England). Who she was is hard to establish, as there were many Sarah Fishers living at Horseley Heath in the 18th century. I would argue that the next owner was Miss Lintorn, who gave it to a Miss Galton. (See the annotations on the left hand page of the picture above.)

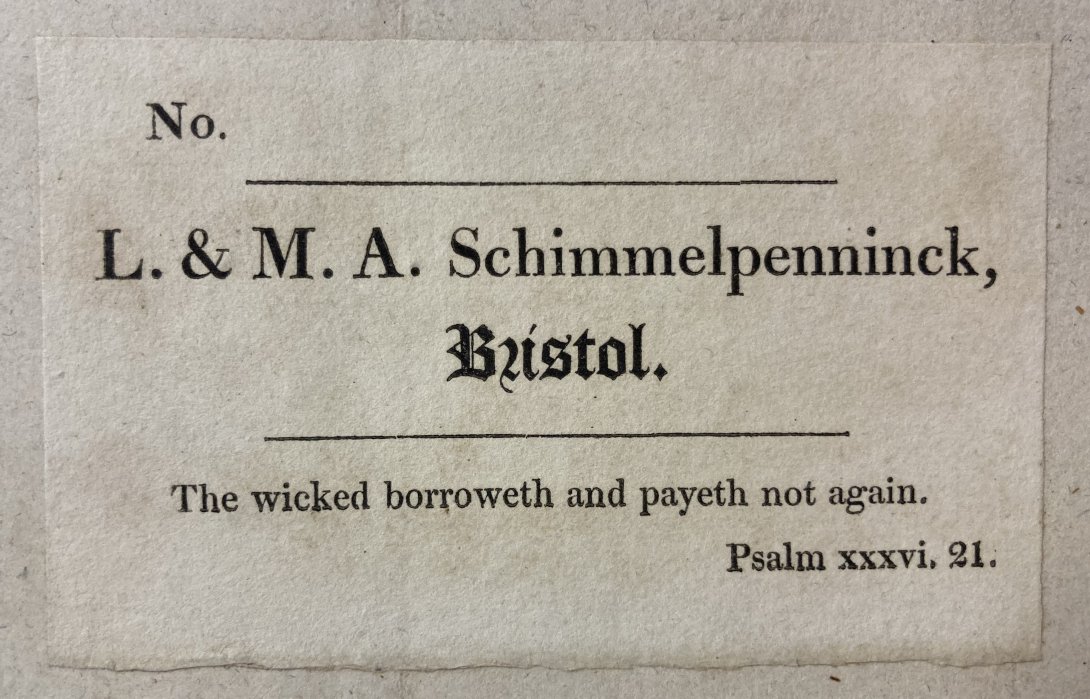

That Miss Galton clearly kept the book. A bookplate adhered to the front endpaper shows that Mary Anne Schimmelpenninck (1778–1856) owned it with her husband Lambert, whom she married in 1806. Mary Anne's maiden name was Galton. Not only was she a relative of Erasmus and the future Charles Darwin, she was also a writer herself and known for her work in the anti-slavery movement. The Schimmelpennincks' bookplate has a stern, Biblical warning for any potential borrower: 'The wicked borroweth and payeth not again'. One of Mary Anne's relatives married into the Clifford family, making it likely it entered the Clifford Collection in the mid-19th century, after Mary Anne died.

The book is beautifully laid out and ornamented, no mean achievement for printer William Bowyer (1663–1737), whose London printing shop and warehouse were affected by fire only a few years before this book was printed. Fire meant that he lost all the type, which was metal.

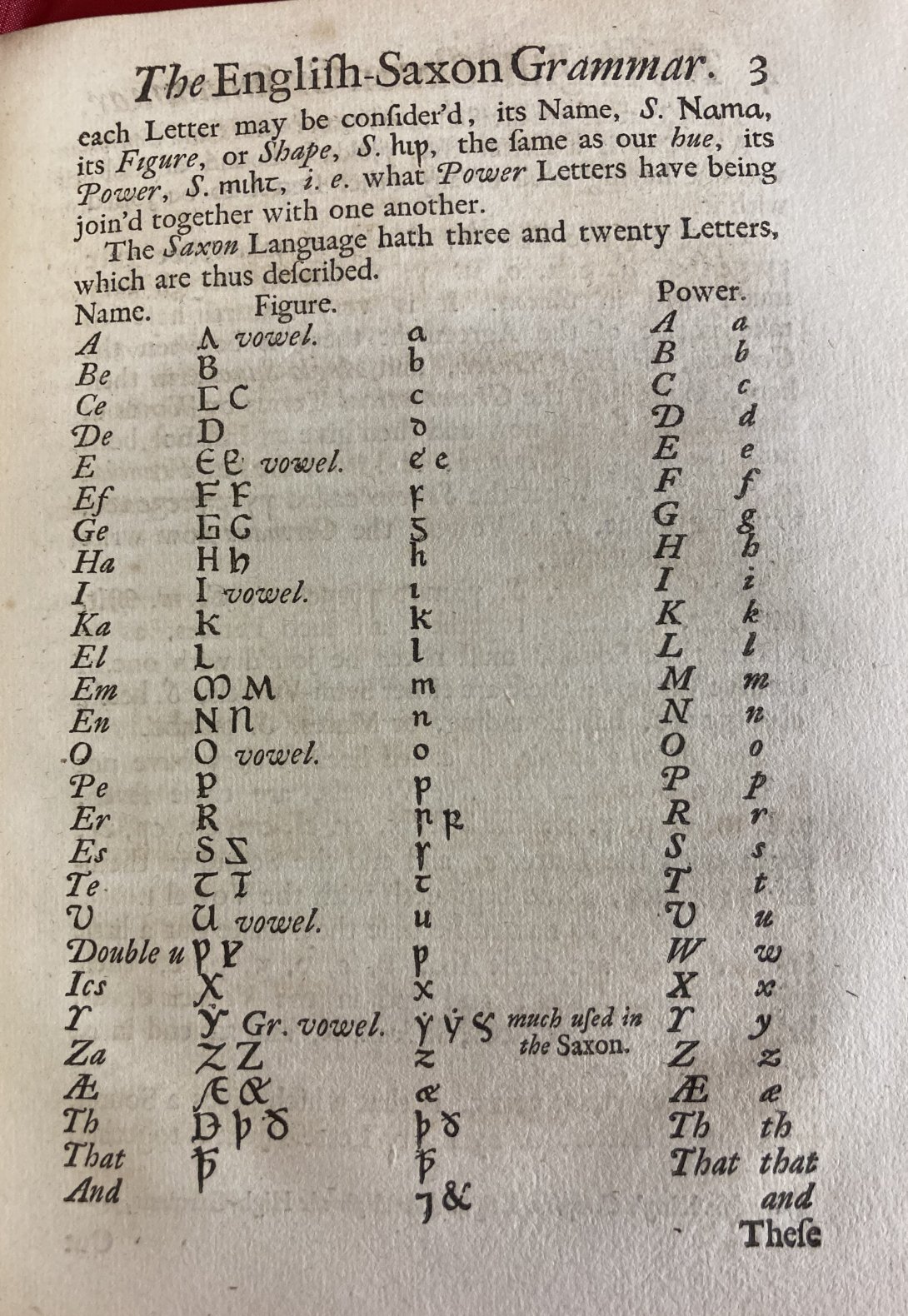

Though by no means the first grammar of Old English, Elstob's was the first in English. By borrowing and copying very early and renowned manuscripts, and engaging with scholars of Anglo-Saxon such as Humphrey Wanley (1672–1726), librarian to the Earls of Harley, Elstob tried to create an historically accurate set of letters for the printers. There is much discussion about how it turned out–the punchcutters were not skilled enough–but it is clear that Elstob's work was a major achievement for any scholar of the time, regardless of gender. Four ledgers for the Bowyer firm survive at the Bodleian Library in Oxford and the Grolier Club in New York, and are available on microfilm at the Library. The ledgers include a reference to Elstob's type in the 1750s.

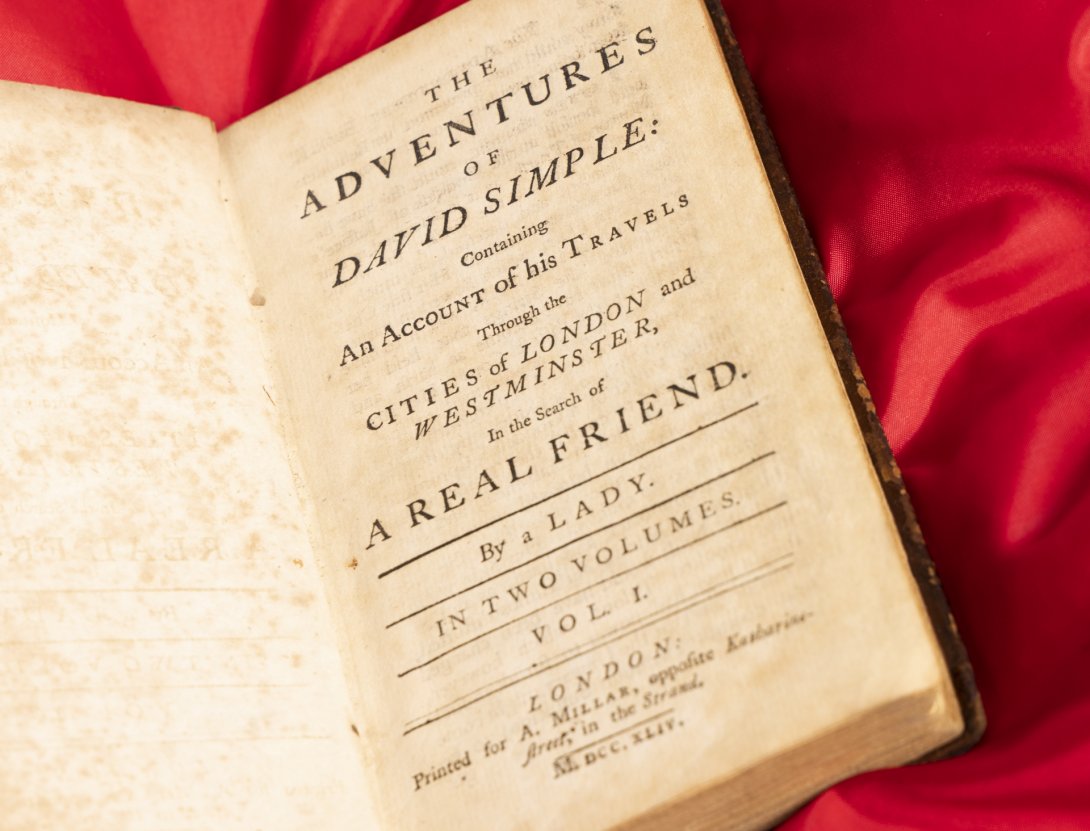

Sarah Fielding

Sarah Fielding (1710–1768) is best known for her book David Simple (1744), a so-called 'sentimental' novel about a naive man making his way in the world. The Library holds the first edition of the novel, which came out in May 1744. She published a follow-up several years later: Familiar letters between the principle characters in David Simple, and some others (1747). Sarah's writing was overshadowed by the success of her brother Henry Fielding (1707–1754), author of the picaresque novel and bestseller Tom Jones (1749). Sarah contributed to her brother's work, including a letter in his novel Joseph Andrews (1742). Financial troubles and early deaths plagued the Fieldings; so she spent her life buffeted on the waves of fortune, moving from relative to relative, dying in Bath. Sarah was well read and skilled in languages–she published a translation of Xenophon's Memoirs of Socrates (1762) from the Greek. She was also well-connected in the literary world, a friend of the author Samuel Richardson and the mother of Elizabeth Montagu, founder of the bluestocking circle. There is no known surviving portrait of her.

David Simple's publisher was Andrew Millar (1707–1768), a Scottish-born bookseller. He was a key part of the syndicate of booksellers to finance Dr Johnson's Dictionary (1755). Sarah and her brother published numerous books with Millar, most famously Tom Jones, of which the Library holds a first issue of the first edition.

This first edition of Sarah Fielding's David Simple is very rare.

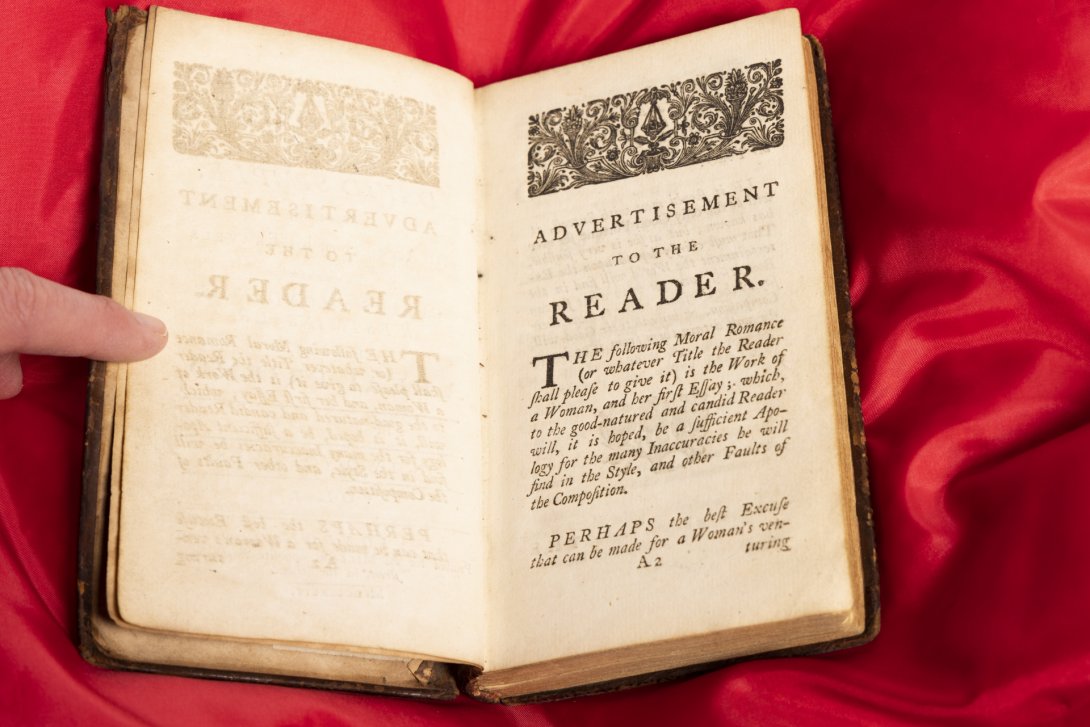

My modern classics paperback uses the second edition of David Simple, which was released in July 1744, with substantial rewrites and revisions by Henry. Some have argued that these were not always an improvement. The first edition is important as it includes Sarah's 'Advertisement to the Reader', which did not appear in the revised, second edition.

The following Moral Romance (or whatever Title the Reader shall please to give it) is the Work of a Woman, and her first Essay; which to the good-natured and candid Reader will, it is hoped, be a sufficient Apology for the many Inaccuracies he will find in the Style, and other faults of the Composition.

Perhaps the best Excuse that can be made for a Woman's venturing to write at all, is that which really produced this Book; Distress in her Circumstances: which she could not so well remove by any other Means in her Power.

If it should meet with Success, it will be the only Good Fortune she ever has known; but as she is very sensible, That must chiefly depend upon the Entertainment the World will find in the Book itself, and not upon what she can say in the Preface, either to move their Compassion, or bespeak their Good-will, she will detain them from it no longer.

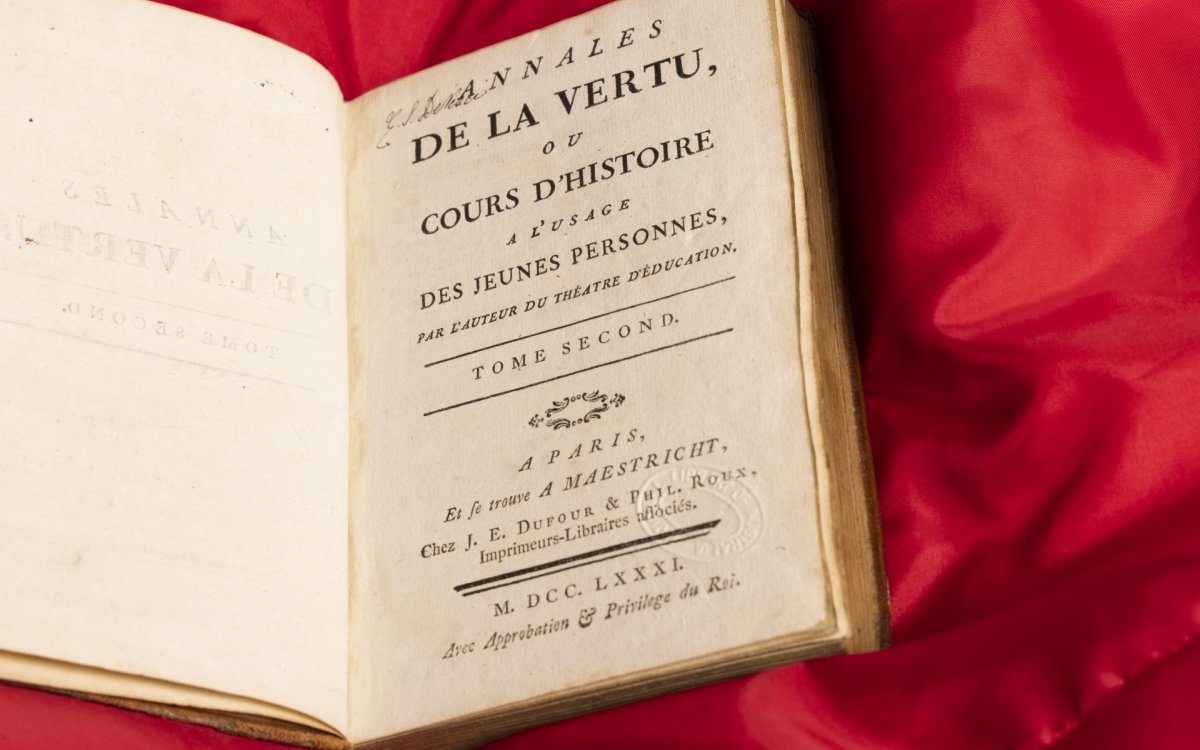

Stéphanie de Genlis

Stéphanie, Comtesse de Genlis (1746–1830) was a prolific French author, best known for her educational works, including Adéle et Thèodore. One of her earliest positions was as governess of the Duc de Chartres, with whom she then began an affair. She was a relative of Madame de Montesson, wife of a relative of the French king.

Madame de Genlis was widely read, including in translation in England. Jane Austen refers to her in her novel Emma and in a letter to her niece Caroline of Wednesday 13 March 1816: 'You seem to be quite my own Neice in your feelings towards Mde de Genlis. I do not think I could even now, at my sedate time of Life, read Olimpe et Theophile without being in a Rage.' Novelist Fanny Burney met her and wrote: 'Poor Madame de Genlis! how I grieve at the cloud which hovers over so much merit, too bright to be hid but not to be obscured.'

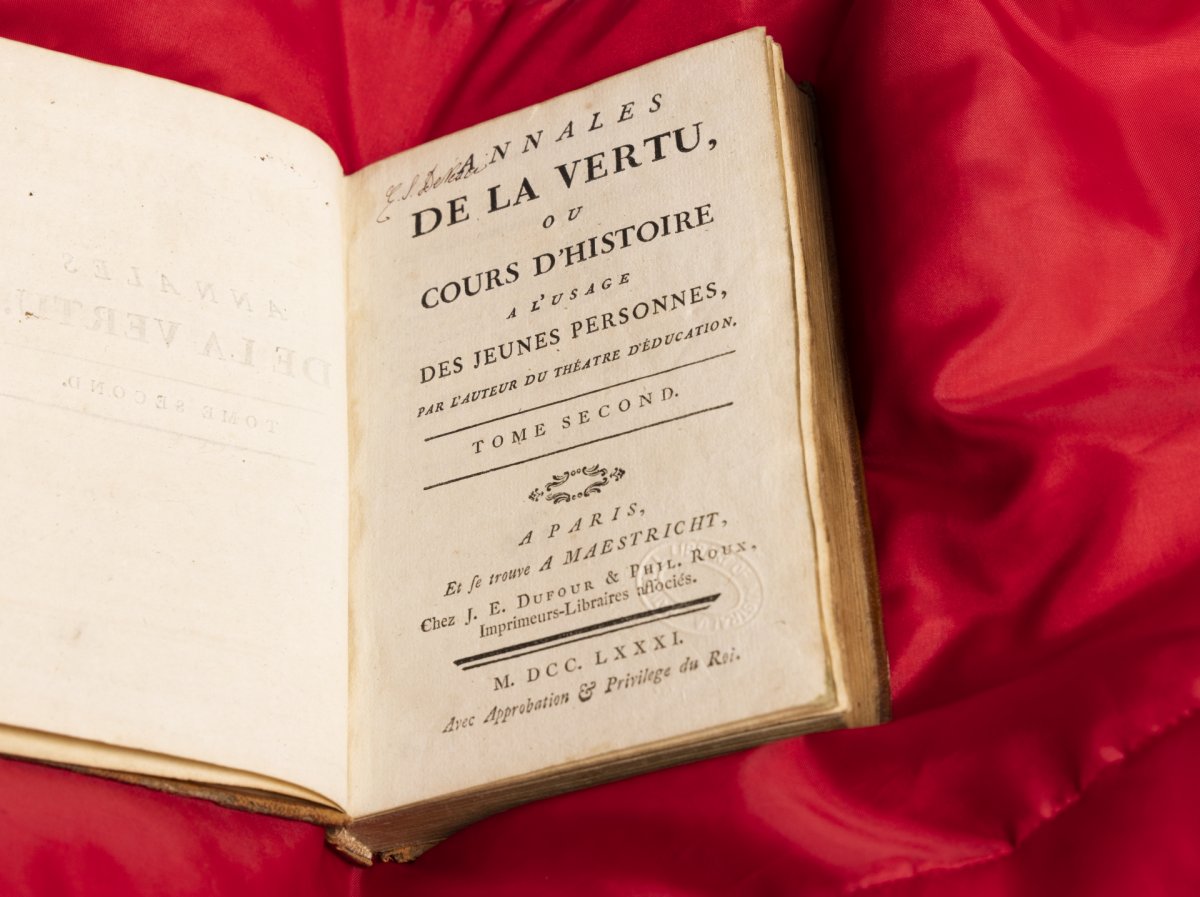

This is one of Madame de Genlis' educational works.

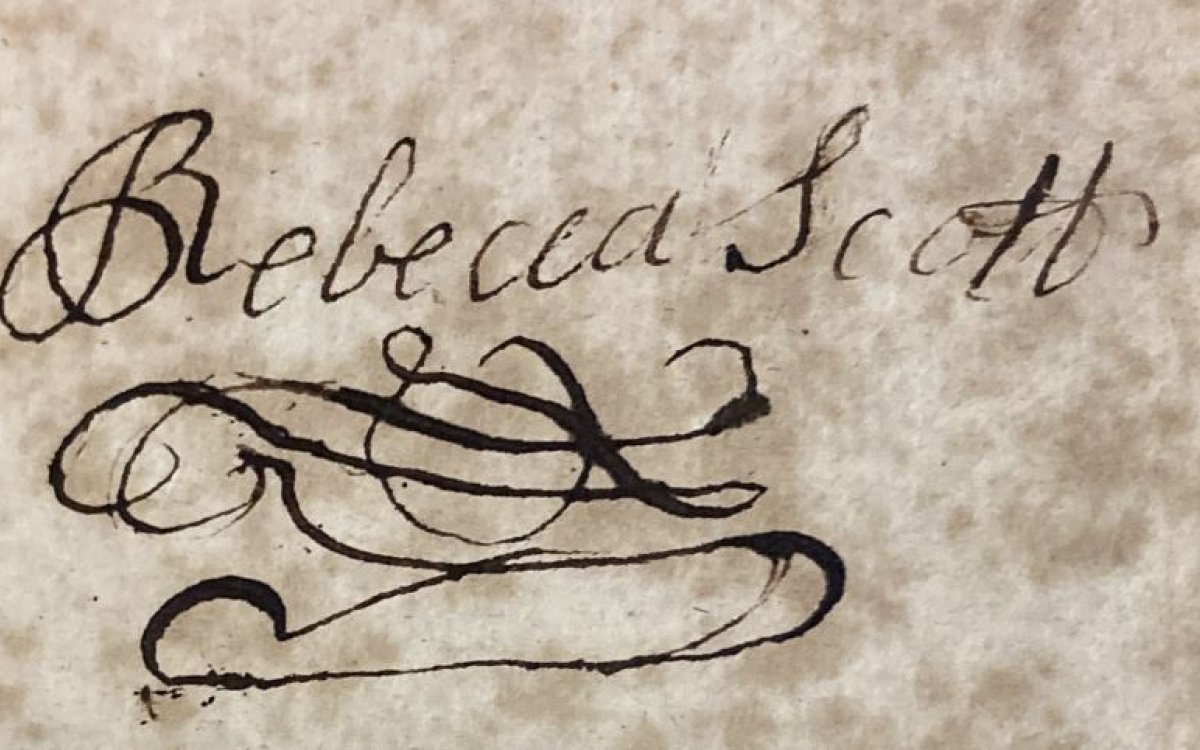

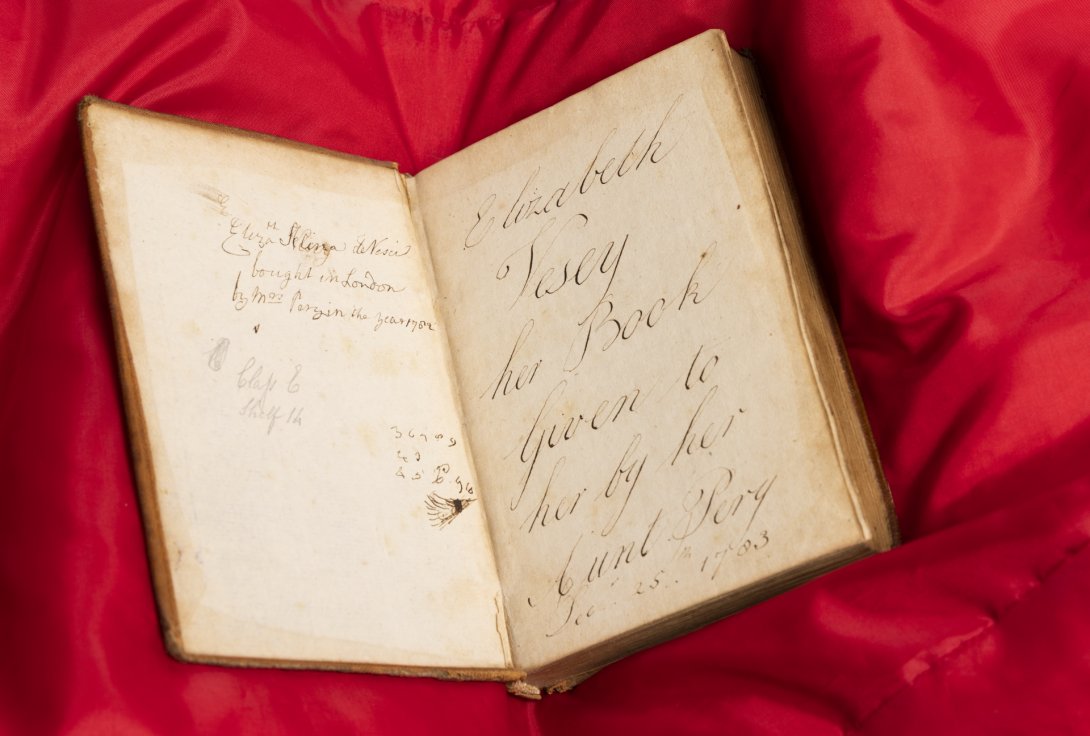

It is the original French edition. What makes it particularly interesting are numerous inscriptions by a young Elizabeth De Vesci (b.30 January 1772), who was nearly twelve at the time she received the book. She was the daughter of Thomas Vesey, 1st Viscount de Vesci (c.1735–1804). She not only inscribes her names in numerous ways, perhaps a little too prominently, but details that it was a gift from her aunt 'Pery'. Her aunt Pery was also called Elizabeth, and had married as her second husband Edmund, Viscount Pery.

Fanny Burney

Fanny Burney (1752–1840) was among the most successful writers of her time. She is better known today, however, for her life and diaries, though her novels are still widely available. Hers was a large and talented family. Christened Frances, she was the daughter of musicologist Charles Burney, and sister of James Burney (known as Jem), who sailed with James Cook on his second and third Pacific voyages. The Library holds one of his manuscript journals from the second voyage. Aged forty-one, she married a French refugee, and had a son. Diagnosed with breast cancer, she had a mastectomy without anaesthetic, and wrote about it. She outlived most of her family and died in her 88th year.

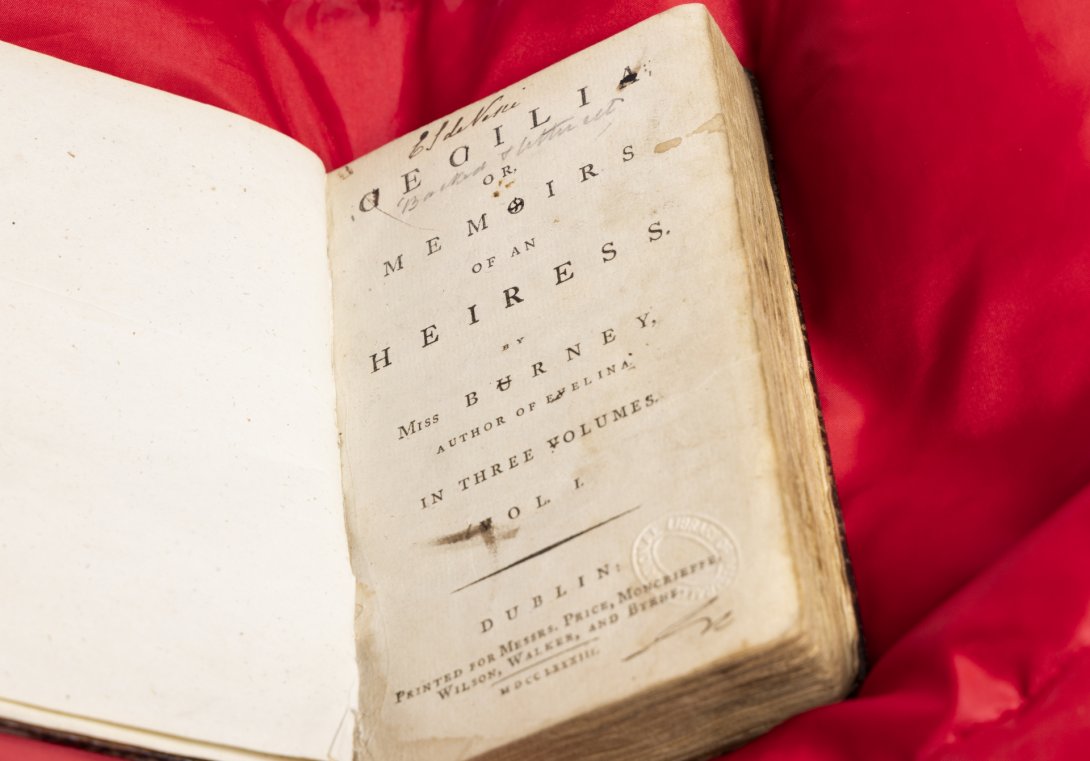

Burney published 4 novels and many plays, and edited her father's writings, though much later in life. Fearing her father's disapproval, she published her first novel Evelina (1778), surreptitiously. It being a runaway success, however, turned her father into an enthusiastic supporter. Her second novel Cecilia was likewise successful.

Cecilia is one of the most well-documented books ever published. Through Burney's spirited letters, we can experience its finalisation as she did. It was published on 12 July 1782 by two London printers in five volumes. 2,000 copies were printed for the first print run. In early 1782, she was copying out a fair copy for the printer to work from. She wrote to her sister Susanna on 11 February 1782:

I am dreadfully busy, & would not write to any human Being but yourself for any pay, so horribly aches my Hand with Copying. – I have just finished that drudgery to the 1st volume.

On 9 July 1782, she wrote to her sister again:

The Book, in short, to my great consternation, I find is talked of & expected all the Town over. My dear Father himself, I do verily believe, mentions it to every body; he is fond of it to enthusiasm, & does not fore-see the danger of raising such general expectation, which fills me with the horrors every time I am tormented with the thought.

Fanny's fears were unfounded. The book was well-received and sold well. Political theorist Edmund Burke sent a highly complimentary letter, which delighted her. Aside from a reservation about the number of characters, he was very positive:

My best thanks for the very great instruction and & [sic] Entertainment I have received from the new present you have bestowed on the publick. There are few I believe I may say fairly none at all that will not hold themselves better informed concerning human nature their stock of observation enriched by reading y[ou]r Cecilia.

Though the Library does hold the first, London edition of 1782, printed for T. Payne and Son and T. Cadell (RB CAM 377), the Dublin edition, printed the following year has more interesting inscriptions and features numerous ink splotches. This copy was inscribed by E.S. de Vesci, who was likely the mother of the Elizabeth we met above. Her name was Elizabeth-Selina de Vesci (née Brooke) (1726–1785).

Mrs Robinson, known as 'Perdita'

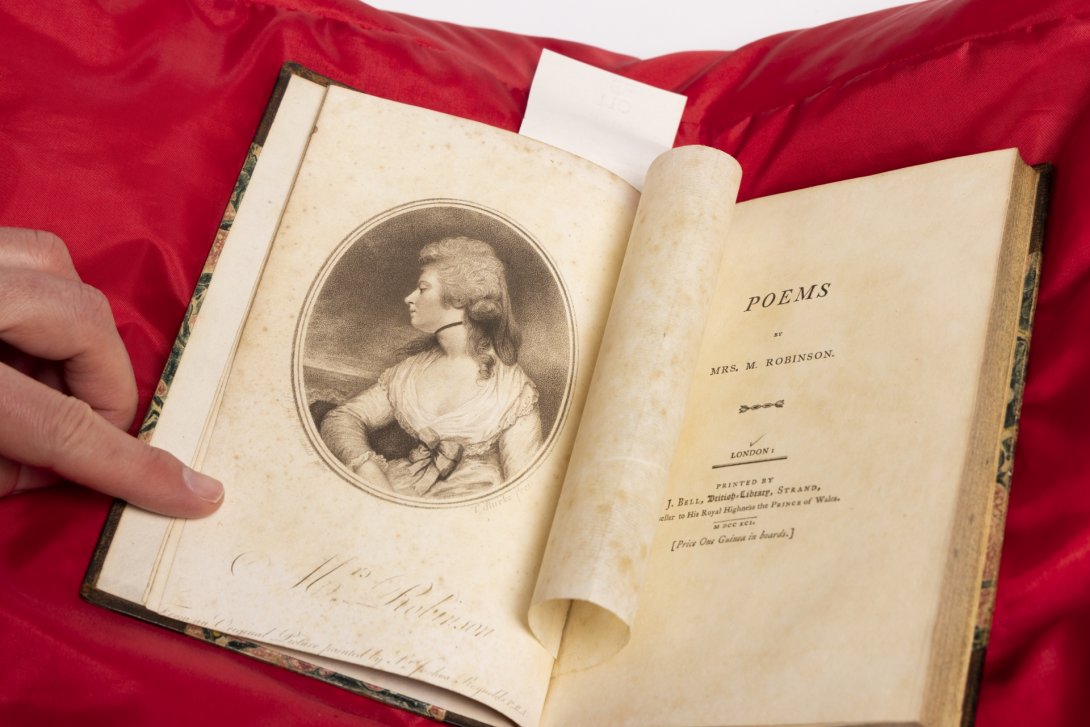

Mary Robinson (née Darby) (1758–1800) known as 'Perdita', was one of the most celebrated, if not notorious, British women of her time. She packed a huge amount into her short life. In addition to a substantial literary output, she was a teacher, then an actress, a favourite of the actor David Garrick and a socialite. Early in her married life, her husband was committed to a debtors' prison. She lived in prison with him and their daughter, before leaving him. She became known as Perdita after her role in Shakespeare's The Winter's Tale, a role which drew her to the attention of the then seventeen-year-old Prince of Wales, the future George IV. She was his mistress for a year.

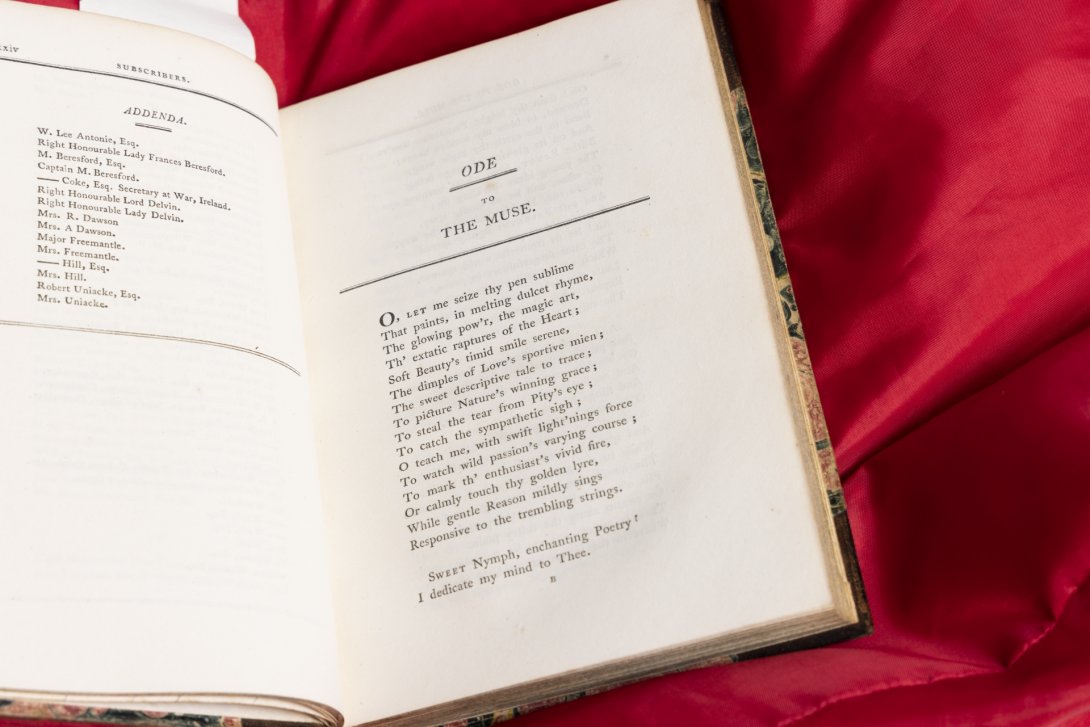

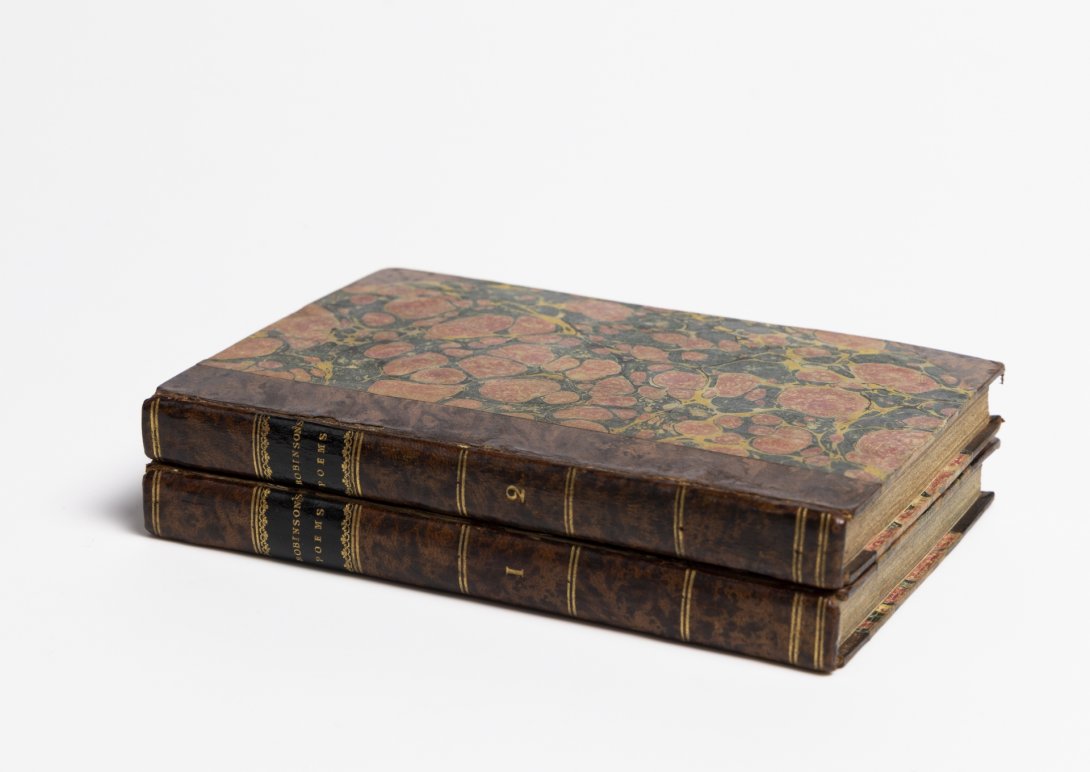

The Library holds two first editions of Mary Robinson's Poems (1791–1793). The first volume (pictured) was in effect a collection of previously published work, which had been published under various names in different publications. Unlike her first book of poems (1775), this one was a success. Robinson has used an engraving of a painting by Sir Joshua Reynolds as the frontispiece to the book. She is known to have loved this portrait.Reynolds was a good friend. The original oil painting, dating from 1783–1784, is held by the Wallace Collection, in London.

The publisher of Robinson's Poems was John Bell (1745–1831), who had a shop called the 'British-Library' on the Strand in London. He was bookseller to the Prince of Wales. He made innovations, commissioning a new font–caslon–and took the step of doing away with the long 's' in his publications. He is best known for his edition of Shakespeare and his 109-volume series The Poets of Great Britain Complete from Chaucer to Churchill (1777–1783). Publisher and editor Charles Knight called Bell 'a mischievous spirit, the very Puck of a bookseller', referring to Shakespeare's character in A Midsummer Night's Dream.

Robinson's book had a huge number of subscribers, about 600, topped by the Prince of Wales, with whom she was still on friendly terms. Subscription was a way of raising money for a book in advance, ensuring profitability. An advertisement in London's Morning Herald newspaper of 15 February 1792, about Mary's next book Vancenza; or, The Dangers of Credulity (1792), tells us what happened next with the first volume's subscribers. After saying that 'A few remaining Impressions of the fine Edition of POEMS' are still available from Bell's shop on the Strand: 'The Subscribers who have not yet paid their Subscription, are respectfully requested to send it to Mrs. Robinson's House, No. 42, Clarges-street, Piccadilly.' The advertisement ends with numerous favourable reviews of the Poems.

Mary Wollstonecraft

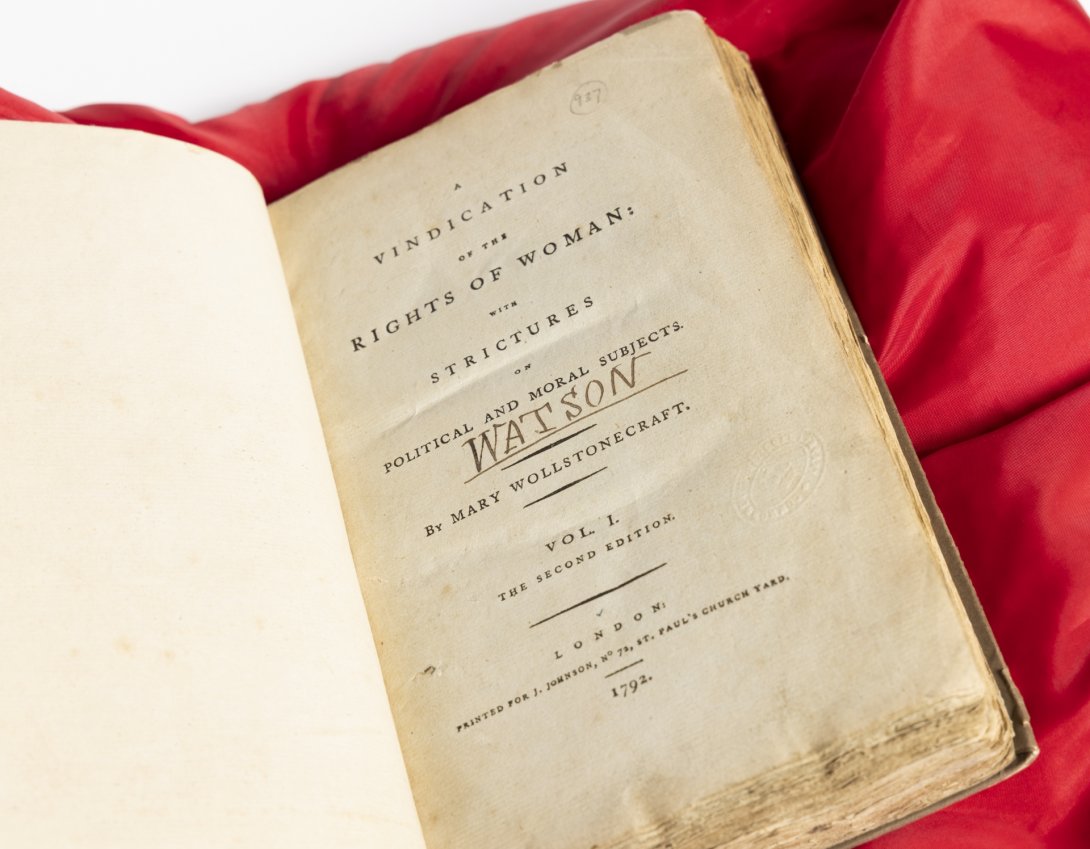

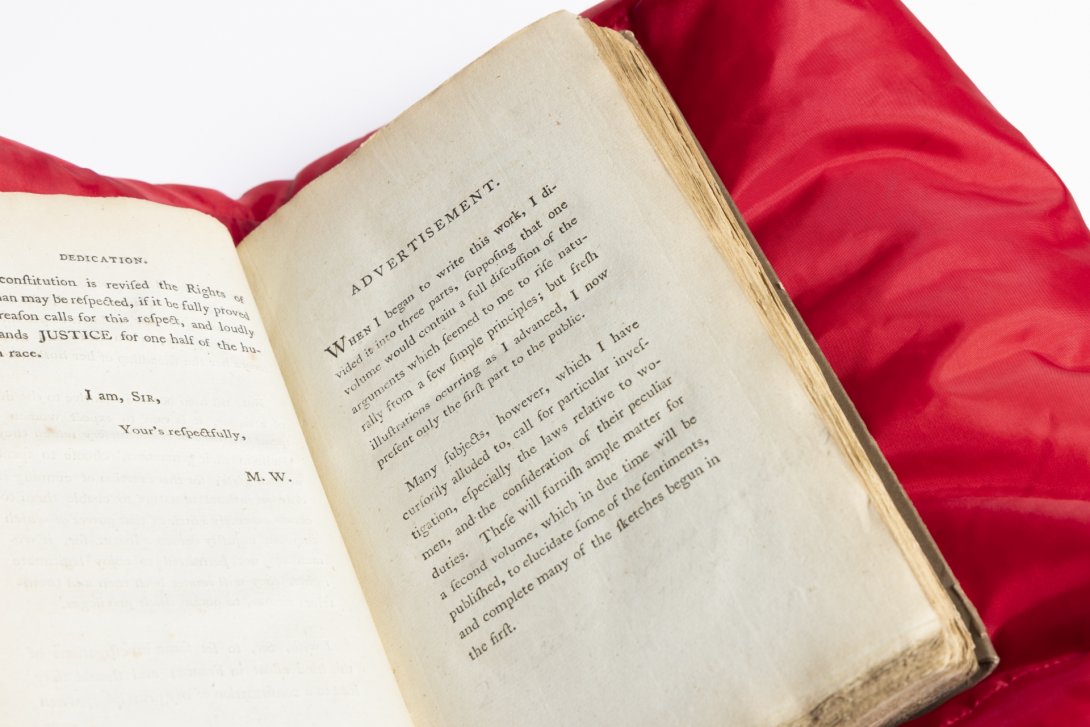

With her polemic A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792), Mary Wollstonecraft (1759–1797) cemented her place in the canon of history's great thinkers. She argues for the importance of women's education.

She wrote it in response to a pamphlet by Charles Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord of 1791 (a French bishop and great political survivor) and she dedicates the book to him, outlining her argument:

Contending for the rights of woman, my main argument is built on this simple principle, that if she be not prepared by education to become the companion of man, she will stop the progress of knowledge and virtue; for truth must be common to all

She expands upon her argument in the introduction:

I wish to shew that elegance is inferior to virtue, that the first object of laudable ambition is to obtain a character as a human being, regardless of the distinction of sex; and that secondary views should be brought to this simple touchstone. ... intellect will always govern.

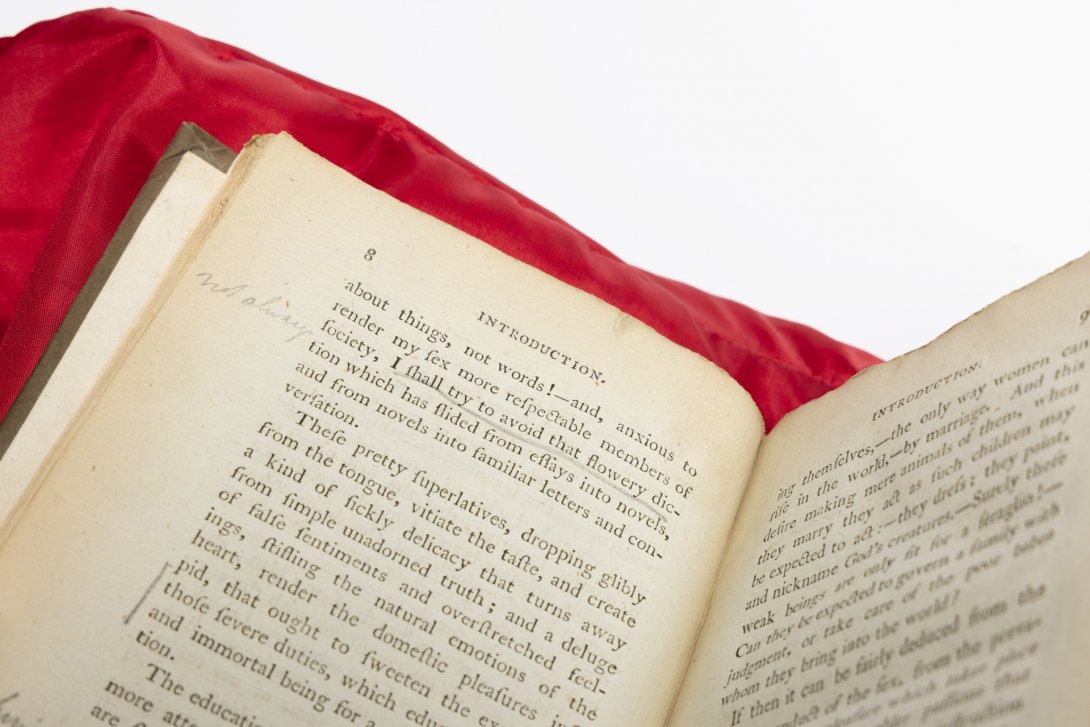

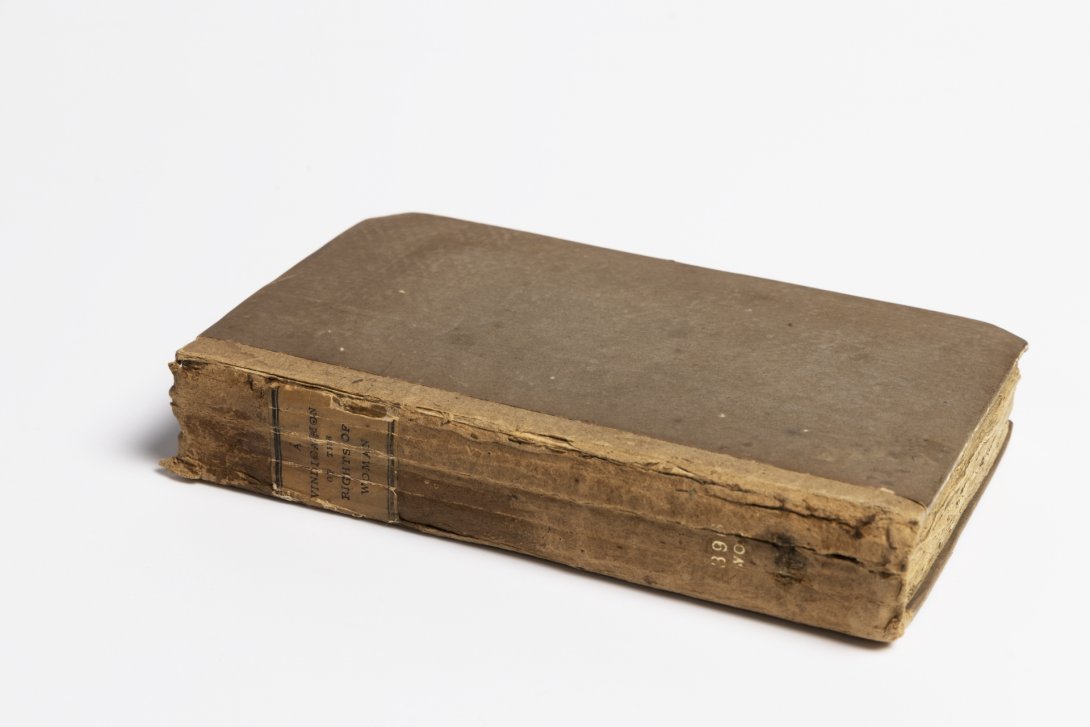

The Library's copy of the book is the second edition, published in the same year as the first. The first edition had mistakes, which she corrected for this edition.

It is modest-looking, cheaply bound and untrimmed, as it would have been at the time it was printed. It has great presence. It is also full of annotations in ink and pencil, hopefully made long before it entered the Library's collection in 1950. These annotations show how readers reacted to the book.

Like almost all of Mary Wollstonecraft's books, it was published by Joseph Johnson (1738–1809). Johnson was a bookseller publisher, with a shop at the centre of London's publishing world, opposite Christopher Wren's St Paul's Cathedral at no. 72, St Paul's Church Yard. Though at the heart of the trade, he was also on the outer of society as a dissenter (a Baptist). Somewhat radical, he was a champion of many of the great free thinkers of his age. The poet William Cowper, little known today, but one of the most famous poets of his day, was one of his authors. The artist William Blake, worked for him; the painter Henry Fuseli was his lodger for a time. Mary Wollstonecraft wrote for Johnson's journal the Analytical Review, and it was at his house, where Johnson conducted business and weekly dinners, that she met her future husband, the writer William Godwin. Godwin was the father of Mary's second daughter, the future Mary Shelley, author of Frankenstein. Wollstonecraft died eleven days after giving birth to her.

Johnson was a constant and reliable figure in Wollstonecraft's tumultuous life. In an undated, often-quoted note, she wrote to him:

You are my only friend–the only person I am intimate with.–I never had a father, or a brother–you have been both to me ever since I knew you–yet I have sometimes been very petulant.–I have been thinking of those instances of ill-humour and quickness, and they appeared like crimes. Yours sincerely, Mary

Johnson was known for keeping prices down by having his books printed outside of London. Many of his books, as is the case with this one, do not name the printer. Having a number of printers on hand allowed him to publish a book quickly.

The Library also holds the Dublin edition of A vindication of the rights of woman (1793), three 1794–5 editions of An historical and moral view of the origin and progress of the French revolution: and the effect it has produced in Europe (1794), Letters written during a short residence in Sweden, Norway, and Denmark (1796) and her husband, William Godwin's memoirs of her after her death. These memoirs exposed details of her unconventional life that had hitherto been rather opaque.The Library holds over 140 of Johnson's publications.

Ann Radcliffe

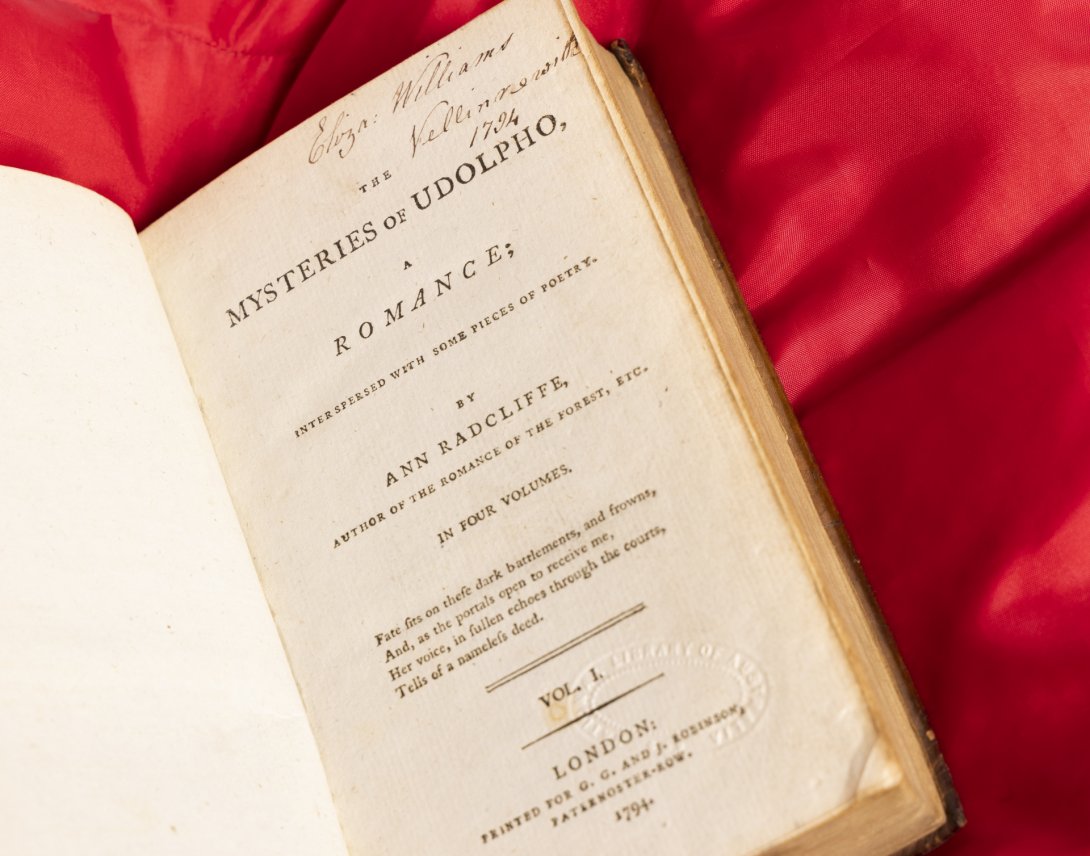

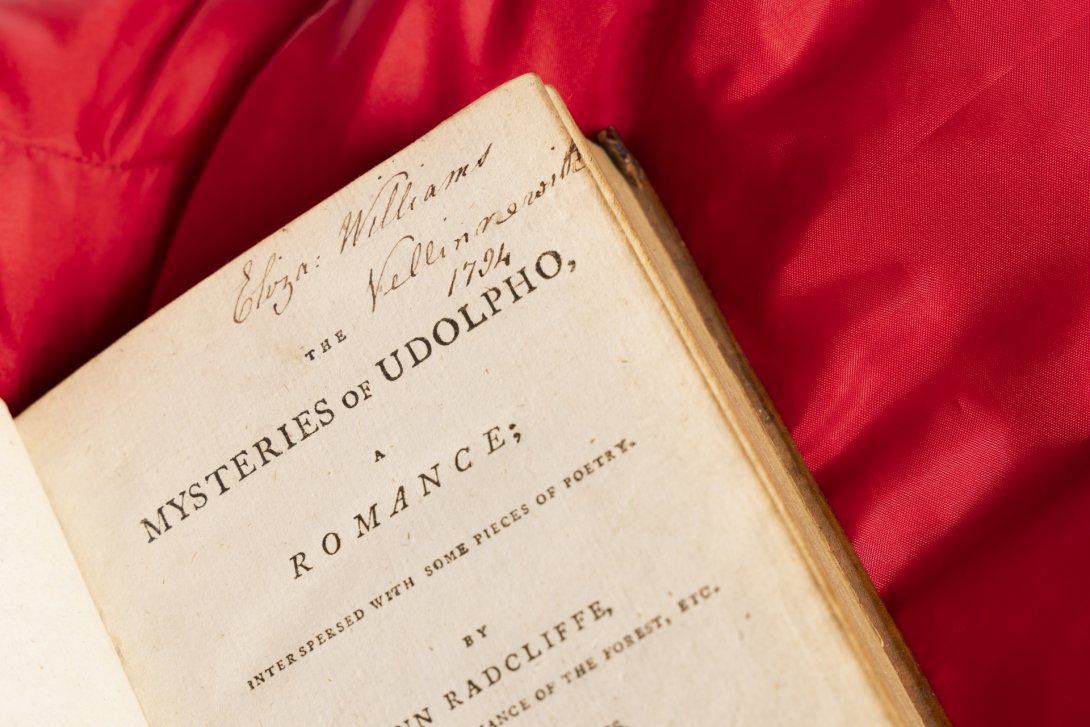

Ann Radcliffe (1764–1823), more commonly known as Mrs Radcliffe, was one of the best-selling novelists of her day. She wrote gothic novels (or romances), which, like Fanny Burney and Mary Wollstonecraft's works, are still widely available in print. The Romance of the Forest (1791), The Mysteries of Udolpho (1794), and The Italian (1797) are among her best known novels. She received 500 pounds for the copyright of Udolpho, twice as much as Fanny Burney had received for Cecilia, the decade before.

The Mysteries of Udolpho is a gothic novel of suspense, set in the 16th century, in south-west France. The main character is a girl, Emily St Aubert, who after the death of her parents, is imprisoned in a medieval castle called Udolpho.

The book came out in May 1794, and though reprinted many times, was never revised by the author or publisher. George Robinson was one of the major London publishers of the time.

Radcliffe suddenly stopped writing in the late 18th century. Exactly why is still debated, though her deteriorating health is often proposed.

This book belonged to a girl or woman, Eliza Williams (likely Elizabeth, as indicated by the colon), living in Vellenoweth, Cornwall, UK in 1794.

These books have real presence not only as lasting historical and cultural achievements, but also as agents of change. The stories they can tell are fascinating, if you have a moment to unravel them. This is just a taste of our holdings. Sign up for a Library card today!

Dr Susannah Helman is Rare Books and Music Curator at the National Library of Australia.