By Sarah Luke, author of Marion and the Forty Thieves

What would happen if you kept skipping school, or were homeless, in NSW 150 years ago? Just like today, the government would try to make you stay at school or give you somewhere safe to live. But unlike today, children who needed help in the nineteenth century were taken to special boarding schools called ’industrial schools’. One of these was a Nautical School Ship, called the Sobraon (pronounced ‘Sa-brawn’).

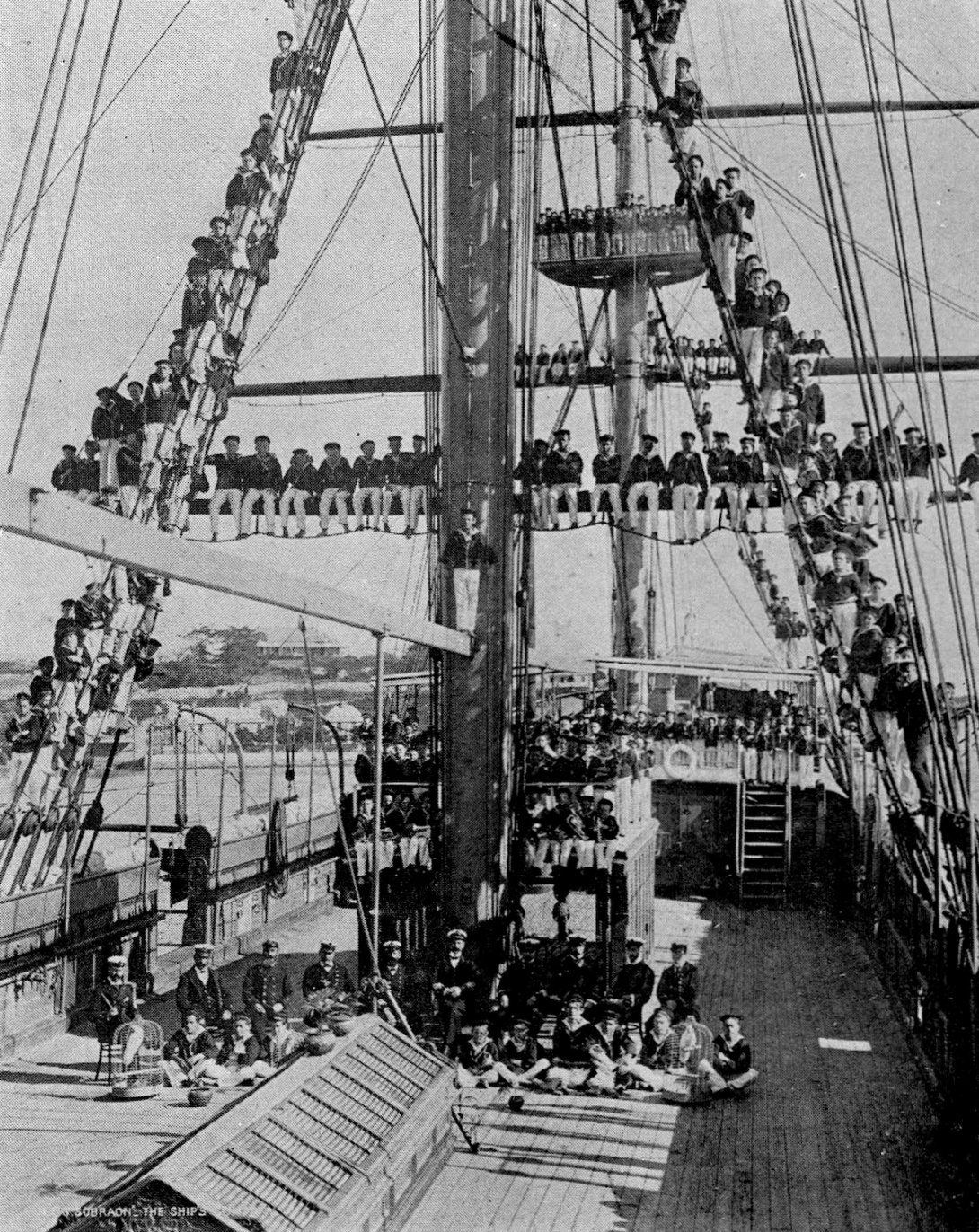

The Sobraon was a huge ship, with towering masts and portholes running along the water’s edge. But it never sailed anywhere: it was anchored next to Cockatoo Island, on Parramatta River, and was full of about 300 boys who were thieves, orphans, or whose parents couldn’t care for them. It was a floating school.

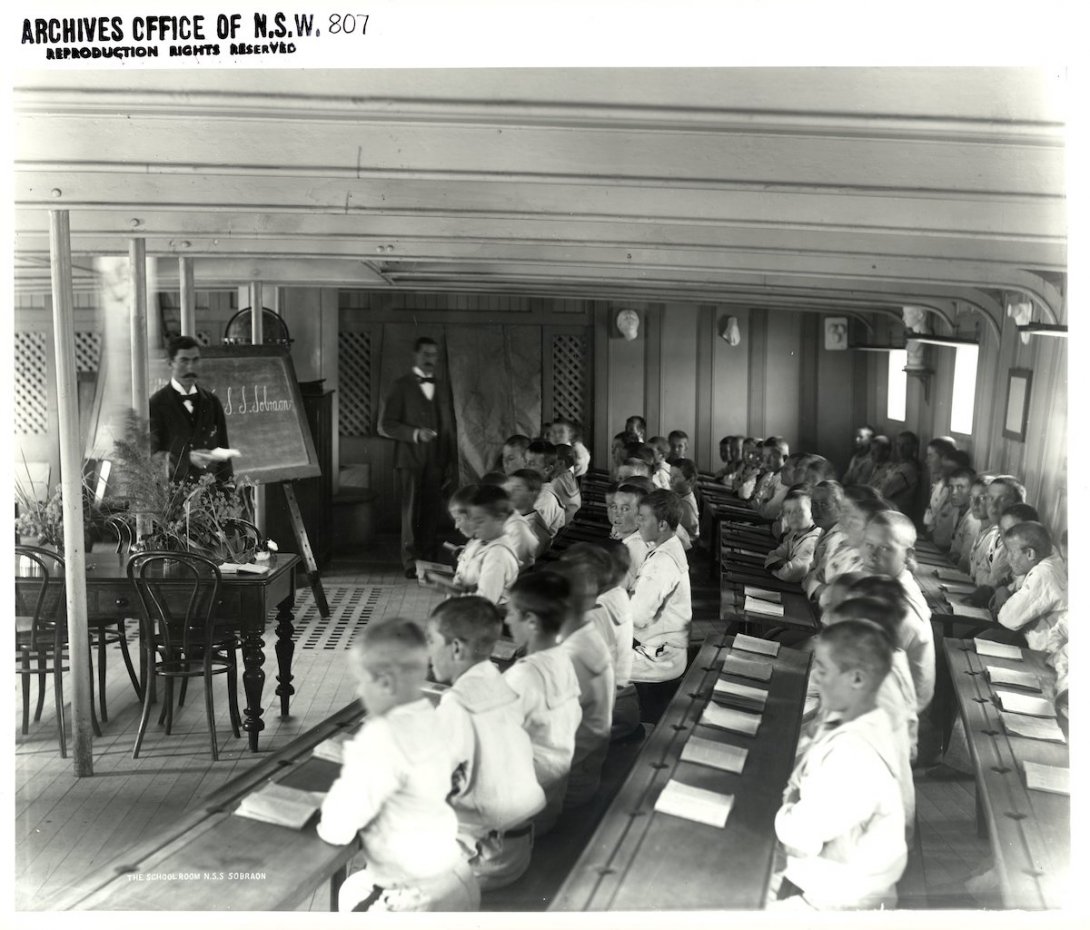

On board, the boys would go to their lessons each day in a room with long curved desks. They learned mostly the same things as students do today—maths, spelling, geography, art. At recess, they would climb up the masts and balance, with hands on each other’s shoulders, along the yards. Some of them were so high, they would have had a view over all of Sydney. Then, at the signal from the captain, they would spider back down to the deck, and either return to their studies or work to paint and otherwise maintain their ship. In the evenings they could go to the library to read or play sports like cricket or gymnastics on Cockatoo Island. At night, they all slept in hammocks in one big dormitory.

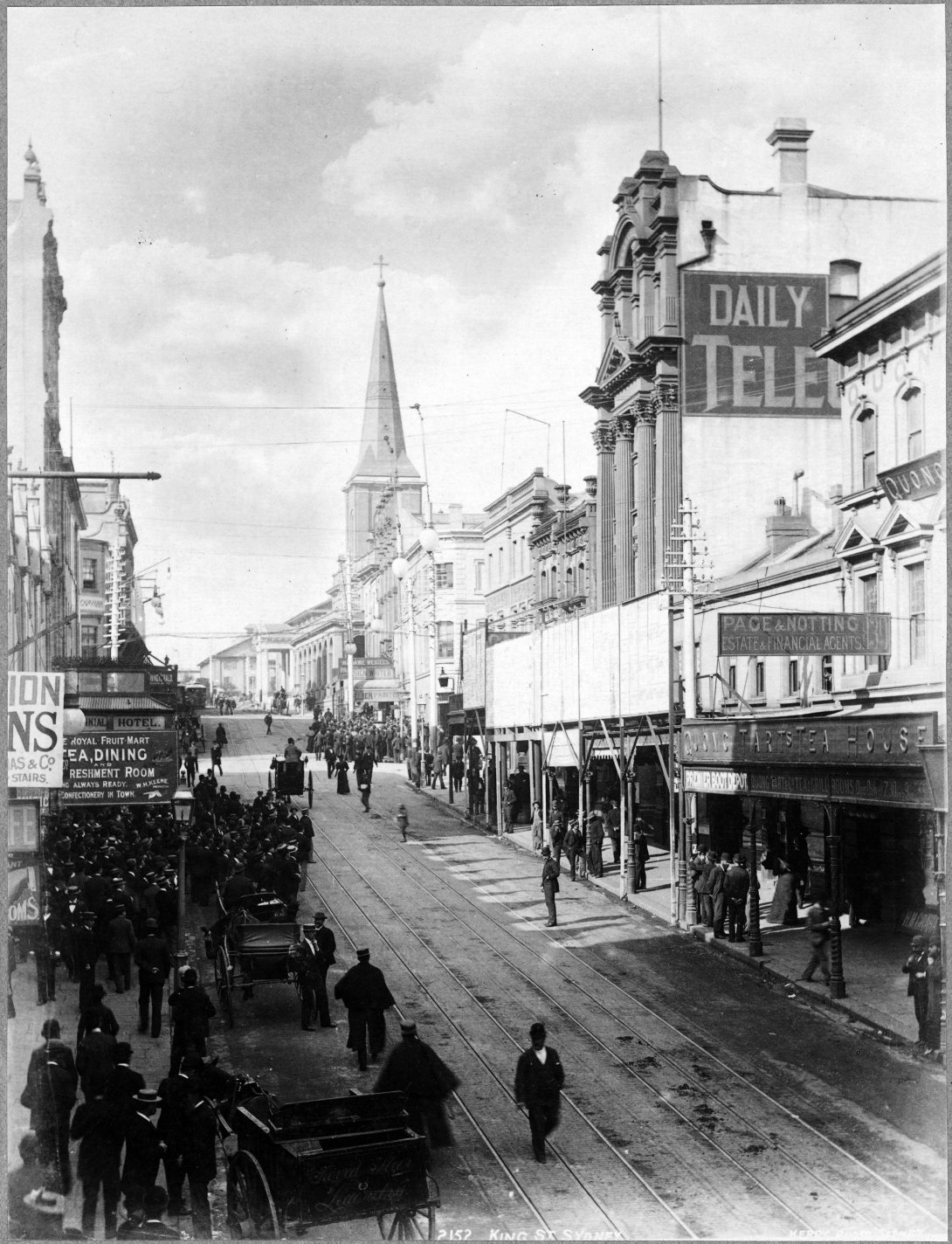

In the 1880s and 1890s, the captain (who was like a school principal) of the Sobraon was a man named Captain Neitenstein (pronounced ‘Nay-ten-shtain’). He lived on board with his wife and only child, Marion. Marion went to a separate school in Sydney, on Elizabeth Street.

A few years ago, when I was researching a non-fiction book about the boys on the Nautical School Ships, I started trying to find out about Marion Neitenstein. I discovered a few things about her: that she was good at Latin and loved animals. When she was a little girl, just six years old, she was mentioned in the newspaper as having given prizes to the boys after a boat race. When she left the ship, aged sixteen, because her father got a new job, some of the Sobraon boys wrote her a letter to say how much they would miss her. They even gave her a present to remember them by.

But I didn’t have enough information about Marion to write a whole non-fiction book, like a biography for instance. So, instead, I made a list of everything I knew about her and the Sobraon while she was there, and then I filled in the gaps with my own imagination.

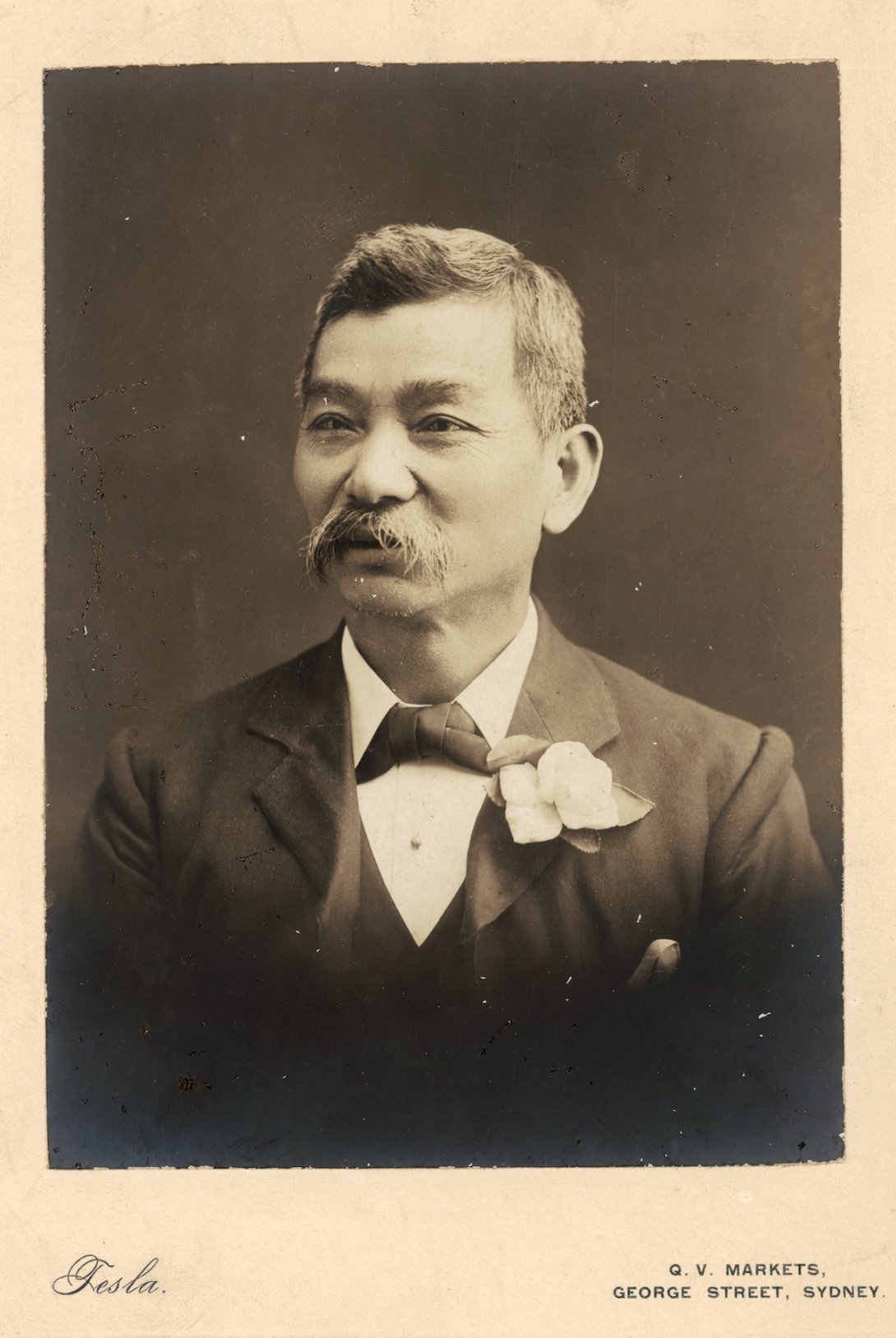

I tried to use the letters and photographs I had to guide me (and photos in the Library’s fabulous collection have been included in my book), so that I could make Marion’s story as real as possible. I even found books and periodicals from the same years, so I could see exactly what the real Marion might have been reading. In fact, lots of the characters in Marion and the Forty Thieves are real people like Marion – Quong Tart the café owner, Marion’s strict parents, and even the nasty, cunning leader of the Forty Thieves gang, Joseph Bragg …