Due to scheduled maintenance, the National Library’s online services will be unavailable between 8pm on Saturday 7 December and 11am on Sunday 8 December (AEDT). Find out more.

Australian writers have a fascination with dystopia. From Tomorrow and Tomorrow and Tomorrow by M. Barnard Eldershaw through to Tomorrow When the War Began by John Marsden, something has compelled Australian creators to write stories of doomsday and beyond. We hold and preserve these speculative futures, keeping them safe so that these imaginings of the end will persevere. Legal deposit is one of the ways that the Library collects tales of cataclysm, making sure that should the worst ever happen, we would still have something worth reading.

This is the way the world ends

Lots of writers have hypothesised about the end of days, and some of Australia’s most famous science fiction stories have explored moments before, during, and after the apocalypse. Following WWII, technological advancement in weaponry meant that the possibility of the world being wiped out by war had gone from a distant nightmare to potential reality, and many sci-fi and speculative fiction writers responded to these fears through their craft.

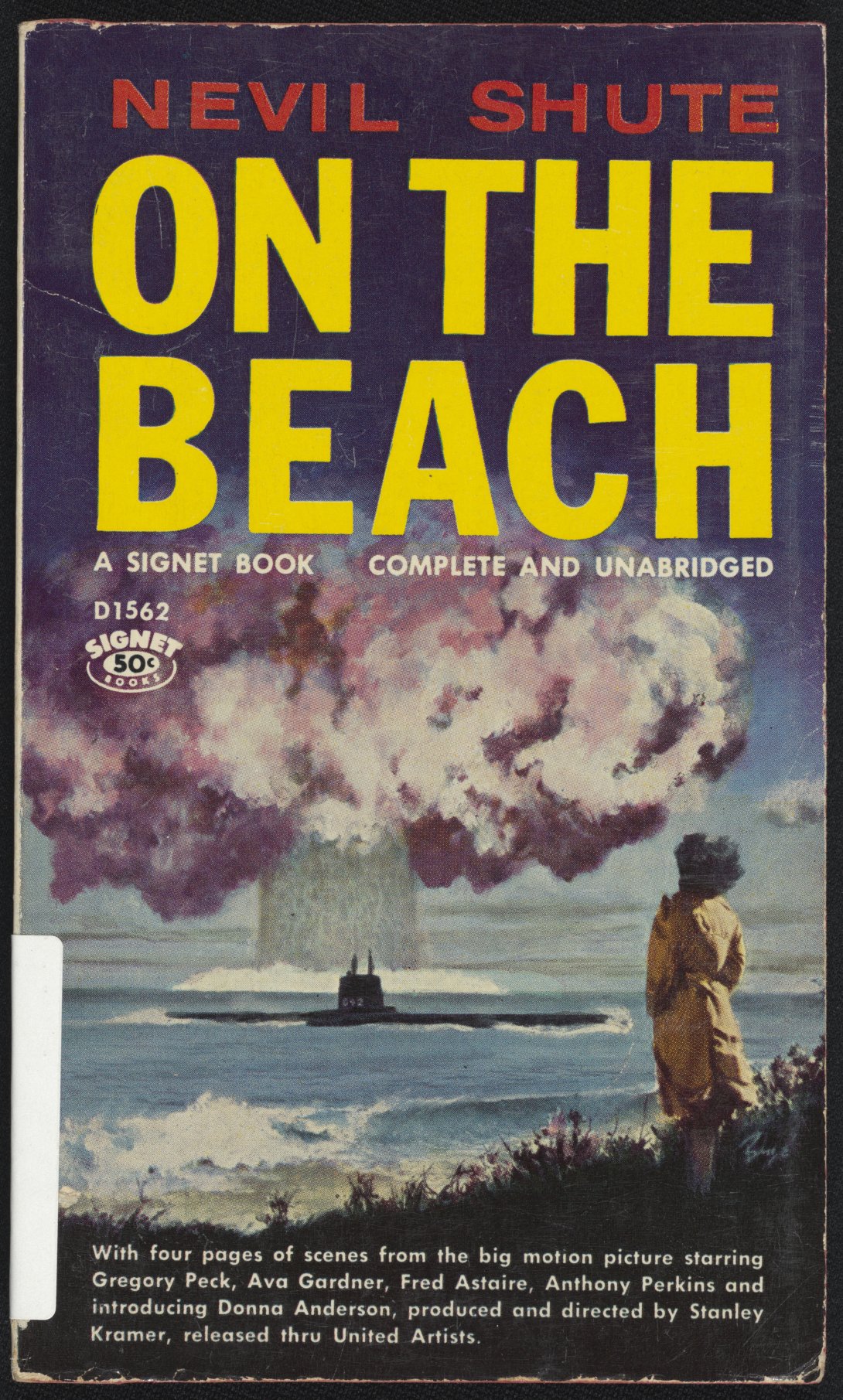

One of the most famous anti-nuclear novels ever written was On the Beach by Nevil Shute. Set in Melbourne, it documents the final days of humanity as fallout from a nuclear war in the Northern Hemisphere creeps its way south of the equator.

Where many apocalyptic novels see characters fighting to survive the end of the world, in On the Beach the lack of opportunity to prevent the inevitable takes the conflict out of the story. The end has already happened, and the story instead explores the time before it arrives.

The characters in the story respond to their impending deaths in different ways, from denial to depression, but in the end all are equally doomed. Written in 1957 during the Cold War, the novel was a warning about the potential danger of the nuclear arms race. It is a critique of inaction in the face of impending destruction, as characters in the story lament not having done more before it was already too late. It served to highlight the horror of mutually assured destruction in a period when there was a genuine risk that nuclear war might happen. The Library's collection includes the first edition of On the Beach, as well as a collection of drafts and unpublished manuscripts of Nevil Shute’s work.

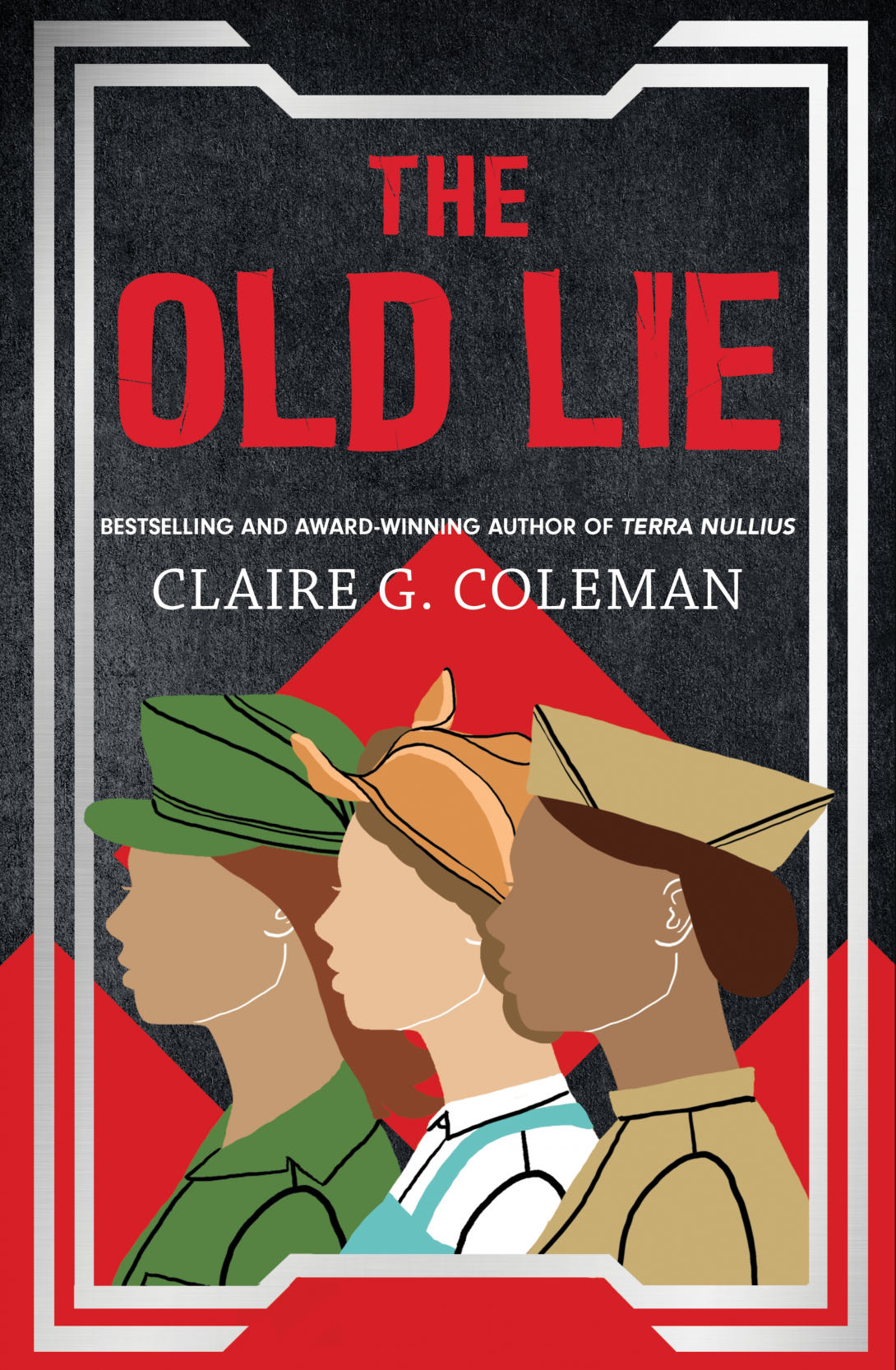

Contemporary fiction continues this use of sci-fi to explore concepts of war, colonialism and dispossession. Wirlomin-Noongar author Claire G. Coleman’s novel The Old Lie takes us beyond the stratosphere, examining the destructive power of war and imperialism on an interplanetary scale. Coleman takes inspiration from the poetry of British WWI officer Wilfred Owen and combines it with her own family’s history of service and mistreatment following WWII.

The novel paints a picture of a bleak future; the world on earth has ended, is currently ending, and has the potential to be ending endlessly. Invasion by intergalactic armies sees soldiers from Earth sent to die and refugees from other galaxies left desperately seeking safety in the hostility of space. Coleman’s narrative sees the concept of Terra Nullius applied to the entirety of the planet Earth. The alien federation Earth aligned with to prevent invasion from other intergalactic forces close the borders of the planet to its own people, denying entry to the human soldiers who had left to defend their homes. This mirrors the mistreatment of First Nations veterans from the Boer War through to WWII, who were not memorialised, never granted the land packages Anglo-Australian soldiers received, and were on some occasions denied entry back into Australia at all.

Life in the dead times

What happens after the world ends? Survivors of apocalypse in Australian fiction have ranged from ex-cop road warriors through to protectors of truth and story defending their culture from destruction. Descriptions of possible post-apocalyptic worlds have been used by writers to take concerns and fears of the present and amplify them into grand narratives; authoritarian control, disparity, desperation, and the destruction and hostility of the natural landscape all feature heavily.

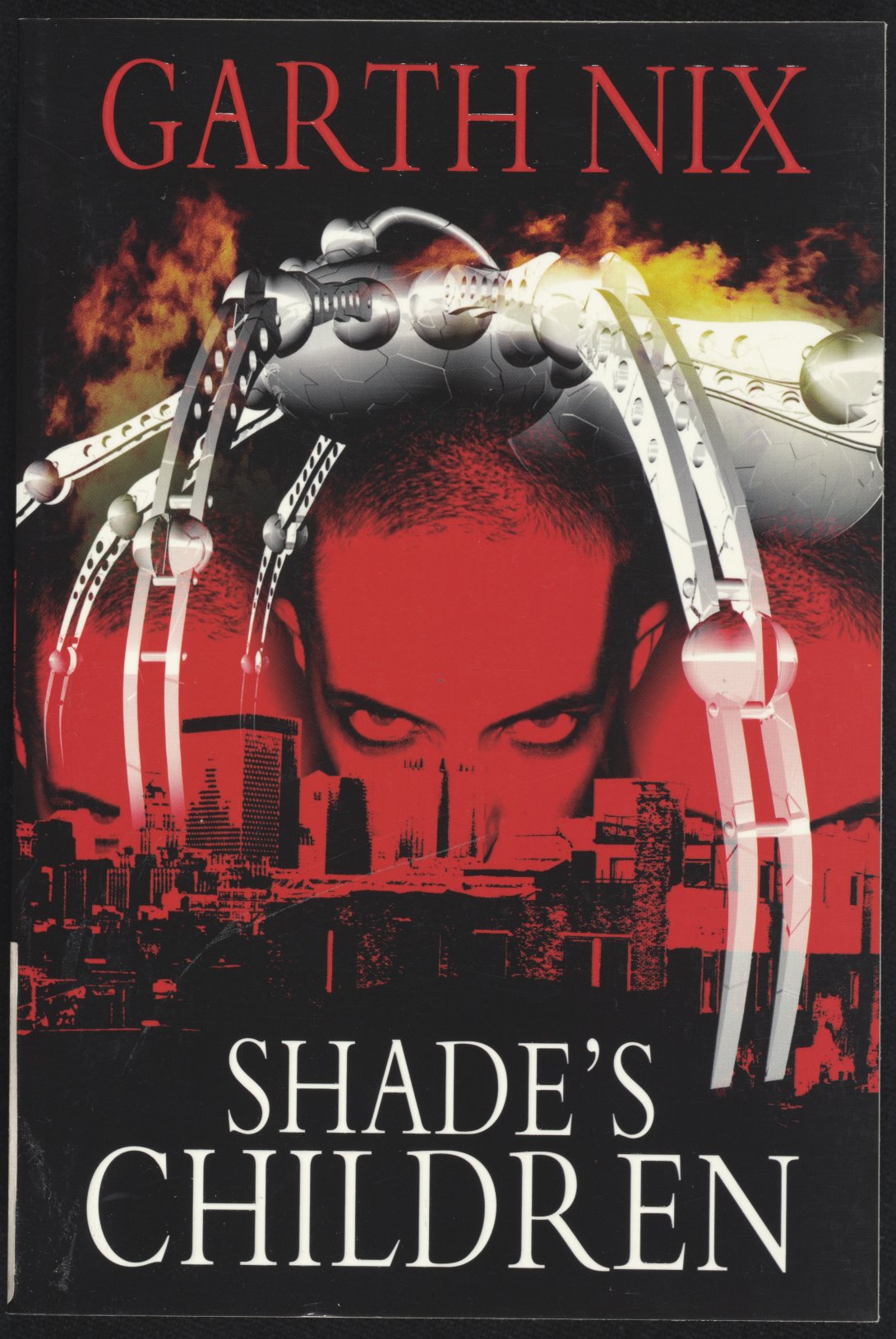

In Garth Nix’s Shade’s Children series, the world has been plunged into chaos following an unknown apocalyptic event, which killed all people over the age of 14. Surviving children continue to live under the control of the ‘Overlords’ who kill anyone over this age and recycle their organs into horrific creatures which are used to continue the Overlord’s control. The story follows teenagers who have managed to escape from this system, and who have come under the stewardship of a computer being named Shade.

The narrative explores the dynamics of power, humanity, morality and the desperation of survival, magnifying these themes through the dystopian lens. The youth of the protagonists highlights certain coming of age themes, with characters finding love against the odds of the brutality of survival, and the feelings of losing your childhood to a world in which the odds are so heavily stacked against you.

Despite the first book in the series being written more than 25 years ago, the story captures the feeling of growing up and becoming a teenager in the modern age, examining the fears of young people staring down the barrel of a world they had no hand in making. In spite of this, the story ends with thoughts of hope, but only at the immense cost of the betrayal of allies, the death of friends, and the suffering of the main characters.

The experience of living in a destroyed and invaded world is not a fiction for First Nations writers. As Palyku speculative fiction writer Ambelin Kwaymullina states in her 2014 article Edges, Centres and Futures: Reflections on being an Indigenous speculative fiction writer in Kill Your Darlings online magazine:

We understand the tales of ships that come from afar and land on alien shores. Indigenous people have lived those narratives.

Kwaymullina’s dystopian novel The Interrogation of Ashala Wolf examines a society that is intended to be perfect, and what that means for those who do not fit into it. Ashala Wolf is the leader of a group of superpowered young people who are deemed illegal by the government thanks to their powers, and who seek to escape this persecution by carving out their own home far from the government’s control. Living in the ‘Firstwood’, Ashala’s abilities come from her connection to her Grandfather Serpent, who resides deep within the landscape and rejuvenates it following the calamity which ended the world. Kwaymullina’s First Nations heritage informs this story as it explores the nature of judgement, who gets to decide what is acceptable, and what happens to those who are deemed not acceptable.

This narrative is about survival when your existence and its value is dictated by a world order that does not reflect all people. However, the story is not nihilistic, it is about resistance. Ashala’s drive to protect her friends and family and face the extremes of the injustices around her is both real and aspirational; it is the informed view of a lived experience.

The sense of looming destruction which haunts apocalyptic narratives arises from the fears of society in the period that they were written. Explored alongside non-fiction works and other primary sources these novels help inform us about lived experience in history, examining political and social dynamics to offer us an alternative way to understand the world we are living in. The Library seeks to keep these stories safe for future generations and Australian writers and publishers can help us with this by contributing their works through legal deposit.

Write yourself into history. Deposit your work at the National Library of Australia.