2021 NLA Fellow Anna Dziedzic’s family has a personal connection to the Library. Her mother worked as a librarian at the National Library in the late 1970’s and early 1980’s, and her brother celebrated his wedding on the Library terrace. Anna also spent a considerable amount of time in the reading rooms in her school and university days. So, after gaining some experience in the Australian Public Service and eventually embarking on an academic career path, she began to consider the possibility of a fellowship here at the Library.

Anna Dziedzic’s current research explores the moment of constitution-making, when the people of a nation decide to change their constitution or make a new one.

What constitutes a new constitution?

‘I first became interested in this topic, and exploring constitution making in the Pacific region, when I realised how long the history of constitution making in the region was,’ said Anna.

‘Some of the earliest written constitutions in the world were made by Indigenous leaders in the Pacific during the 19th century.’

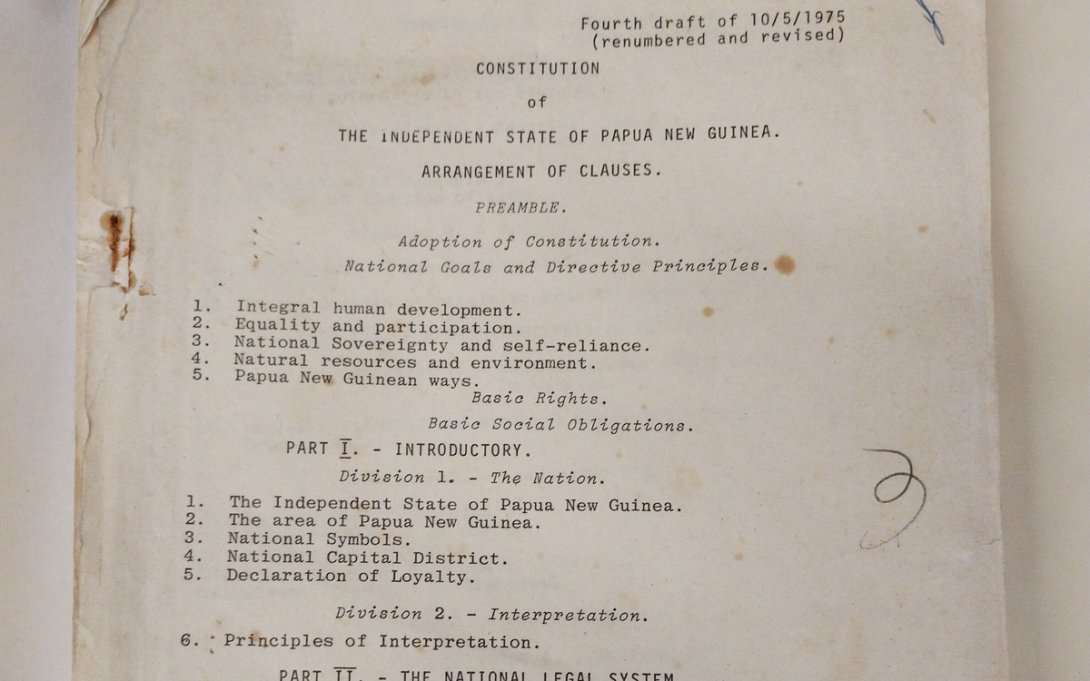

Anna’s focus during the fellowship has been on a more recent wave of constitution-making in the Pacific from the 1960s to 1980s, as colonised nations became independent states and made constitutions to mark self-determination and self-government.

These constitutions are often characterised as ‘transplants’ as they are based on templates provided by the departing colonial authorities and accepted by Pacific states as a necessary step towards independence.

Libby Cass: Yuma and good afternoon and welcome to the National Library of Australia. I’m Libby Cass, Director of Curatorial and Collection Research at the National Library. I’d like to begin by acknowledging Australia’s First Nations peoples as the traditional owners and custodians of this land and give my respect to elders past and present and through them, to all Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Thank you for attending this event and we are coming to you from Ngunnawal and Ngambri country.

This afternoon’s presentation, Waves and Currents: The Movements of Constitutional Texts and Ideas from Oceania, is by Dr Anna Dziedzic, a 2021 National Library of Australia fellow. Our Distinguished

Fellows program supports researchers to make intensive use of the National Library’s rich and varied collections through residencies of three months. The National Library of Australia’s fellowships are made possible by generous philanthropic support and Dr Dziedzic’s fellowship has been supported by the Stokes family.

Dr Anna Dziedzic’s research is in the area of comparative constitutional law and judicial studies with a particular focus on the Pacific region. She is a convenor of the Constitution Transformation Network and Melbourne Law School and coeditor of the blog of the International Association of Constitutional Law. In addition to her academic research, she has provided advice and assistance to constitution making and law reform processes across the Asia Pacific region.

Her fellowship research at the National Library has focused on developing an understanding of second wave constitution making across the islands of the Pacific that moves beyond official accounts by paying attention to the people, relationships and context that lie behind constitutional texts. Please join me in welcoming Dr Dziedzic to tell us more about her research.

Dr Anna Dziedzic: Thank you, Libby, for your kind introduction. I too would like to begin by acknowledging the Ngunnawal and Ngambri peoples, traditional custodians of this land, where I have had the privilege to live and work of the past three months and I pay my respects to their elders past and present. I extend that respect to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples here today. I would also like to welcome Indigenous peoples from the wider Pacific region who are attending here or online.

It has been a real privilege to be a fellow of the National Library of Australia and I thank the Stokes family for so generously supporting my fellowship here. I also thank all of the staff at the library, who have made me feel so welcome and helped me enormously with my research, and the fellowship team of Sharyn, Kelly and Simone, in particular.

I also preface my talk today with a caveat, which is even though the fellowship provided a full three months to devote to reading materials here in the library, I nevertheless ran out of time. Library staff tell me that this is not unusual but it does mean that what I present here today is my preliminary thoughts. I very much welcome your comments and feedback as I continue to work on this project.

So Waves and Currents: The Movement of Constitutional Texts and Ideas Across Oceania. So written constitutions have a long history in the Pacific region. Over the course of the 19th century, in the period following European contact and before colonial acquisition, Indigenous leaders in Hawaii, Tonga, Samoa, Fiji and Tahiti all adopted written codes and constitutions. While some were never implemented, others were put into operation and amended over time. One, the 1875 constitution of Tonga, continues in force today.

A century later, in the period of decolonisation from 1960 to 1980, Pacific countries adopted written constitutions to mark their formal independence from colonial rule. These independence constitutions have proven remarkably resilient. In only two Pacific states, Fiji and Tuvalu, have the independence constitutions been repealed and replaced.

Constitution making continues today. So Tuvalu is currently engaged in public consultations on a new constitution, which squarely confronts the existential crisis of climate change. Bougainville too is in the midst of public consultations on a new constitution on its pathway to selfdetermination and independence.

So these are the waves of my title. The waves of constitution making that swept across the region at particular periods of time. The 19th century constitutions of island polities seeking to ward off the threat of colonisation with a written constitution as proof of selfgovernment. The constitutions made in the 1960s, 70s and early 80s in the period of decolonisation. And what is perhaps potentially a new wave of constitution making in the Pacific, as states and territories in this region lead the way in finding distinctive forms of statehood, of sovereignty and governance in current conditions of global interconnection and the threat of the climate crisis.

My focus here today and the focus of my research here at the library is on the second of these waves, the decolonisation constitutions of the 1960s through to the 1980s. The currents of my title refer to the influences and forces that connect the written constitutions and the exercises of constitution making across the region at these times.

There was and sometimes still is a tendency to assume that the written constitutions of Pacific Island states of this period are connected only by their imperial origins. This assumption is supported by the formal processes of constitution making because some Pacific constitutions in this period became law by legislation or order of the imperial power. These constitutions often share a common structure, language and provisions, which, it is often assumed, were largely borrowed from and perhaps dictated by external sources.

This assumption is also apparent in the orthodox history of decolonisation in the Pacific. The usual story presents decolonisation as a slow evolutionary process, driven more by the departing colonial authority than by Indigenous peoples themselves. So, one scholar characterises the process of decolonisation by Pacific peoples not as a fight for their independence but as having their independence handed to them on a silver platter.

These narratives have been countered by historians who emphasise people centric and Indigenous histories of decolonisation over the top-down accounts derived from imperial sources. Foremost amongst these is Tracey Banivanua-Mar’s book, Decolonisation and the Pacific, which charts the mobility and the agency of Indigenous people across the region and the diverse ways in which they advocated and practised independence within the constraints of the colonial power imbalance.

My foray into this area of research owes a lot to the path forged by Tracey Banivanua-Mar and other Pacific historians and those of you familiar with her work will also recognise her influence in the framing of this project around waves and currents.

The motivation for this project is to situate written constitutions into this kind of Pacific history of intersecting imperial and Indigenous relations. I hope to show how, when considered in this way, it becomes possible to trace distinctive patterns of influence on both the content of written constitutions and the procedures by which they are made in the past and today.

The idea of currents in my title is meant to evoke channels and directions of movement of constitutional ideas, texts and institutions within and beyond the region. The movement of ideas is a characteristic of constitutional development and design the world over. The very idea of a written constitution, which is now taken for granted in all but a few outlier countries, itself spread around the world over time. Particular constitutional innovations, theories and ideas have also spread and continue to do so today.

So while the movement of constitutional ideas is not unique to the Pacific, it strikes me as a particularly important process to uncover in the Pacific context. First and foremost, it pushes back against the idea I described earlier of the unidirectional movement of constitutional ideas from the colonial administration to the newly independent Pacific states. In other words, it potentially broadens and diversifies the sources of influence.

Secondly, it uncovers the genesis of innovations in Pacific constitutional design and their adaptation and refinement as they move. I will speak more of this later and give you an example.

Finally, this is an important exercise because constitutional drafting matters for how constitutions are understood by the people, how they’re interpreted by courts and other constitutional actors and how they change over time to meet new circumstances and new demands.

So waves and currents is an expansive, thematic project on constitution making in the Pacific. I am right at the beginning of it and to be honest, I’m not entirely sure where it might end. In this presentation I present only the slice that I began working on during my fellowship here at the National Library and I call this part “How the Constitution Words.”

So while the waves and currents project sounds a lot like a historical project, I’m not a historian. I am a constitutional lawyer and as a lawyer, constitutions are, first of all, words on a page. Of course, constitutions are more than this. They are institutions of government, principles of how to govern, they are part of national identity. These things, however, are enshrined in writing in a written constitution.

To explain the importance of constitutional words, I draw on the writings of one of the two people whose papers held here at the national library were the focus of my research during my fellowship, constitution drafter C.J. Lynch. I will introduce him more fully in a minute but for now I want to share his thoughts on why the study of constitutional words is important. So he writes in a characteristically self-effacing way and I quote.

“A static study of a constitution is not perhaps the most important type of study and lawyers are not infrequently accused of concentrating on status or nit-picking an arid discussion of mere words, rather than elucidating the true intention of the legislators and on seeing the constitution as an evolving machinery of social control. In other words, say the critics, the important thing is how the constitution words or how it can be used.”

“How the constitution words” is of course a slip here. I think it’s clear that Lynch meant, had in mind to write “How the constitution works.” But I think it’s a prescient slip because he goes on to say that these criticisms ignore at least two aspects of constitutions. Firstly, that the legislation in our system is a verbal thing and it is words that give it its effect and that lay down the limits to the effects possible.

Secondly, if social content is to be put into a written law and if it is to be used as an instrument of control or development, those words must be understood with all their deficiencies as words presumably communicating a coherent message of some sort. Lynch writes like a lawyer with very few full stops. I’m sorry.

Lynch continues, “To use an analogy, it is possible with genius or luck to take a ship or an aircraft over long distances without knowing anything of its structure. On the other hand, the careful navigator would first want to know how the ship or aircraft was constructed, what its structure could stand and so on, before trying to push that structure to its limits, and in the legal field, the learning and imparting of knowledge of this sort is the function of the lawyer,” end of quote.

So, in other words, you can find out a lot from how the constitution words, where those words come from and how they come together. My project seeks to do just that by examining how two people in advising and drafting constitutional text for Pacific states on the brink of independence went about their task. How did they see their role? What sources did they draw on when writing a constitution? And in what ways were these advisors themselves channels for sharing constitutional words and ideas?

So, my fellowship at the National Library provided me with the opportunity to begin this project with a deep dive into the papers of C.J. Lynch, whose words you have already seen, and Professor J.W. Davidson, who together advised on the making of constitutions across eight countries between 1959 and 1985.

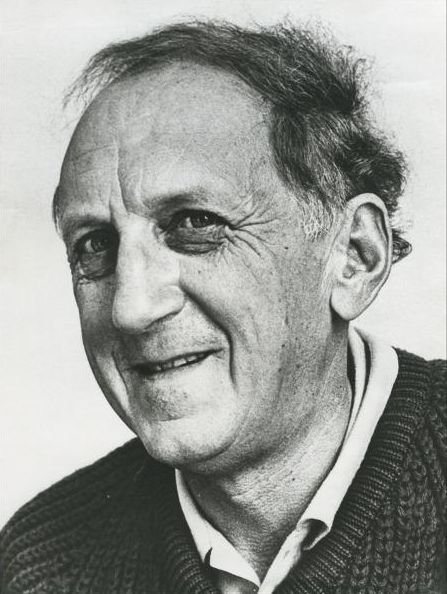

I will start by introducing Jim Davidson, whose story is a little more well known, especially here in Canberra. So, James Wightman Davidson, known as Jim, was born in Wellington in 1915. He is most famous here in Canberra as the first chair of Pacific history at the Australian National University, a position he obtained after completing a doctorate at Cambridge and working in the New Zealand public service and the British admiralty.

Alongside his career at ANU and, as his biographer Doug Munro explains, sometimes in tension with it, Davidson also forged a career as a constitutional advisor in the Pacific. This work began with his visit to Samoa in 1947, while it was administered as a United Nations trust territory by New Zealand. He says that he first went to Samoa as a spy, in his words, sent by the New Zealand government, ostensibly doing historical research but really to see how the government was working in the lead up to a visit by the United Nations to check up on progress in decolonisation.

Davidson was personally very captivated by Samoa. He returned in 1949 to share an inquiry into local government and again in 1959, this time as the constitutional advisor to the Samoan government, to help it prepare a constitution for independence. Samoa became an independent state in 1962.

Davidson was then one of three constitutional advisors to the Cook Islands legislative assembly, as it negotiated its place as an independent state in free association with New Zealand in 1964. In 1967 and 1968, he was engaged by Nauruan leaders to advise them on negotiations for independence and in writing its constitution in 1968.

In 1969 and 1970, he was a consultant to the Micronesian congress, as it negotiated with the United States for selfgovernment and independence. Finally, in 1972, Davidson was appointed as an advisor to the constitutional planning committee in Papua New Guinea, which was charged with writing a constitution for independence. He was working with this committee in Port Moresby, when he died suddenly on 8 April 1973. Papua New Guinea became an independent state with a new constitution on 1 September 1975.

C.J. Lynch is not so well known as Jim Davidson. When I began my fellowship, the only biographical details I had were those on the National Library catalogue. I didn’t even know his full name, I only had C.J. to work from. However, and thanks in no small part to my mother’s exceptional skills in family history as well as what I could glean from his papers, I was able to find out a little more about his life and work.

So, Cyril Joseph Lynch, Joe, was born in Albury in 1924. His father was a teacher and barrister. Joe, it seems, was a talented student. He won several school prizes at Marist Brothers, Darlinghurst and St Joseph’s College, Hunter Hill and he was awarded a bursary to the University of Sydney in 1941.

World War Two intervened, however. Lynch joined the RAAF as a flying officer. His plane was shot down and captured by German forces on 6 November 1944 and he was held as a prisoner of war in Germany until the end of the war in May 1945. His father, it seems, was also a prisoner of war at the same time, but in Changi.

There is very little mentioned of his wartime service in his papers or in articles written about Joe Lynch, to the point where my mother and I have checked and double checked that it is indeed the same C.J. Lynch. Like many in his generation, wartime service must have been a formative experience and the analogy he makes between constitutions and flying an aircraft takes on a difference significance in this light.

After the war, Joe Lynch returned to Sydney University, graduating with a Bachelor of Laws. He was admitted as a barrister in New South Wales in 1949 and employed as a legal officer in the department of territories. He arrived in Papua New Guinea in January 1952 and within a month was administered as a barrister and solicitor of the Supreme Court of Papua New Guinea and appointed a Crown prosecutor. He served in the department of law in the colonial administration as a Crown law officer and as a legislative drafter.

So, Lynch lived and worked in Papua New Guinea until 1979. He was witness to 28 years of great change, as the country moved from being a colony of Australia to an independent state. Lynch was at the centre of implementing this change, as first legislative counsel, responsible for drafting the text of the independence constitution in 1975, a service for which he was awarded an OBE.

After leaving Papua New Guinea, Lynch became a consultant legislative and constitutional drafter. He worked in Kiribati and Marshall Islands, in both cases to draft laws to implement new constitutions. He also worked in Tuvalu, where after a brief time as attorney-general, he was employed to help draft a new constitution to replace Tuvalu’s independence constitution with one that more closely reflected the wishes of the people. He passed away in 1985 before this new constitution of Tuvalu came into force in 1986.

So, Davidson and Lynch share some similarities as external providers of assistance to constitution making. However, the differences between them are instructive. Davidson was a historian and a constitutional advisor. Lynch was a lawyer and constitutional drafter. Davidson, only nine years older than Lynch, was of a different generation in his constitutional advising career. The ways and means of decolonisation and independence and of constitution making changed markedly over the timespan of the decolonisation wave from 1959 to 1986. So, the way they saw their roles and acted in those roles was quite different.

So, Davidson was described by fellow Pacific historian, Harry Maude, as “A constitutional midwife to nascent island communities.” His role as a constitutional advisor seems to have been to advise local leaders on the best path to independence in negotiation with the colonial power and, where relevant, the United Nations. A written constitution was part of this independence process, not least because it signalled to the colonial power and the rest of the world that the Pacific polity was more than able to govern itself.

Davidson’s biographers and Davidson himself saw his best asset as the trust which Pacific leaders had in him and his advice. This trust was partly the result of strong personal relationships. As early as 1951, he said, “In Samoa, my main advantage was that of simply liking the people and taking them seriously.” As time went on, this trust was also a product of his success. Samoa, Cook Islands and Nauru had all successfully achieved independence with his involvement.

It was also due to his deep commitment to selfgovernment and in particular that constitutions and laws should be based on the wishes of the people, rather than the colonial administering power. This commitment to local ownership was ahead of its time, but now is a foundational principle in constitution making.

His model of work as a constitutional adviser was functional and pragmatic and directed towards the ultimate goal of selfgovernment and independence. In his words, a constitutional advisor must be in large measure a politician as well.

As constitution maker, however, Davidson’s approach comes across, at least to my eyes, all of these years later, as sometimes a little high handed. In Samoa and again in Nauru, Davidson worked with a small group of officials from the Pacific country and the departing colonial power to prepare a draft constitution. In this role, Davidson himself oversaw the drafting of the provisions, working closely with legislative drafters seconded from Australia or New Zealand. This draft constitution would then be considered by a convention of representatives, article by article.

Davidson championed the idea that a convention of representatives of the people should be responsible for making the constitution. In this way, the constitution would belong to the people themselves and not be imposed on them. In Samoa and Nauru, Davidson took the lead role in the conventions, introducing and explaining each article before responding to questions and engaging in the debate. In Samoa and Nauru, the conventions tended to adopt the provisions in their original draft form or with very minor changes.

Not all of the representatives in the conventions were happy with the draft provisions or with this directed approach to the work of constitution making. In Samoa, there was a great deal of debate about the ways in which the constitution could enshrine Indigenous custom and chiefly institutions of governance. Davidson advocated against including such innovations in the text of the constitution, arguing that such details were better left out of the constitution and hinting that departures from the standard model of a western constitution might not be favourably received by the United Nations when it came to determining Samoa’s independence.

In Nauru, Davidson responded to similar proposals by saying, “The best answer one can give is that we are now providing a constitution that is made by representatives of the Nauruan people under which citizens of Nauru alone will hold executive and legislative office. This is the best assurance of a proper regard for Nauruan custom,” end of quote.

This was not the approach to the constitution making taken in Papua New Guinea. There, a committee of parliament, the constitutional planning committee, was established in June 1972 to make recommendations for a constitution for full internal selfgovernment in a united Papua New Guinea, with a view to eventual independence. Davidson was appointed as an advisor to this committee. There is also evidence that he and his former doctoral student, David Stone, were involved in discussions with chief minister Michael Somare and others about the composition and mandate of the planning committee prior to its creation.

Several other advisors were also hired by the constitution planning committee. In its early meetings, Davidson and other advisors would present papers on various constitutional issues to guide discussion, somewhat similar to the processes in the Samoan and Nauruan working groups. Before too long though, the constitutional planning committee developed its own ideas and working procedures, which included extensive consultations with the public.

Historian John Ritchie describes how in 1973, after Davidson’s death and with the launching of an extensive program of public consultations, the Papua New Guinean members of the constitutional planning committee no longer relied on the expatriate advisors for what ideas to discuss, but themselves directed the issues that were then taken up for further research and analysis by advisors. Significantly, the committee did not draft a constitutional text, but made recommendations which were discussed and modified before being handed over to a drafter, which was Joe Lynch.

So, Joe Lynch took quite a different approach to constitution making. He was a lawyer and legislative drafter by trade and he acted on instructions. Whereas Jim Davidson described the role of a constitutional advisor as political, Lynch describes his role as quite technical. In relation to the constitution of Papua New Guinea, he wrote, and I quote, “I was the legislative draftsman responsible for the draft constitution that was presented to the constituent assembly. That does not mean that I was personally responsible for policy or even in all respects the wording, but it does mean that I am the one to be blamed primarily for any technical faults.”

His choices in drafting mattered, however. For example, there were some uncertainty about who had the authority to issue final drafting instructions to Lynch, whether it was the executive government, led by Michael Somare, or the constitutional planning committee, led by John Momis, and the two sometimes clashed with Lynch caught in the middle.

Reading between the lines, I think Lynch was more sympathetic to Somare or had more influence with Somare. For example, we hear echoes of Lynch’s concerns about the length of the constitution in Somare’s preference for a constitution that was a short statement of principles about the structure of government, with details left to organic laws, a solution it seemed Lynch devised.

This is not to say that Lynch was completely reactive. On the contrary, his papers show that he generated a lot of innovative constitutional ideas. These ideas were presented as working papers for discussion in Port Moresby throughout the 1960s. Some were put into public submissions to various parliamentary committees, while others were the subject of conversations between Papua New Guinea and leaders, officials in the administration, judges and scholars.

One motif that’s repeated in Lynch’s writings is the “Why not?” question. So writing in 1964, a time when the introduction of selfgovernment was being discussed, Lynch acknowledges a prompt by Cecil Abel, who was a leading political figure in Papua New Guinea, and he writes that “It was he”, meaning Abel, “Who, when I, thinking in terms of traditional British colonial development, complained that we could not just develop a cabinet system under the existing constitution because we could not expect local ministers to operate successfully now. Abel said, in effect, ‘Why not?’ Given that simple change of attitude, the rest was only a relatively minor research job,” end quote.

Although they had different approaches to providing constitutional advice, Davidson and Lynch did share a common vision of what a constitution is. For both, the constitution was ideally a short statement of principles to outline a system of government. Both were opposed to adding detail, believing that this was better left to ordinary legislation or to be developed in practice. Lynch was more expressly in favour of constitutional change over time. He even advocated a standing people’s assembly or a committee of parliament to monitor the performance of a constitution and propose changes.

This functional technical vision of a constitution was not necessarily what all Pacific Islanders wanted, however. I mentioned before the attempts in the constitutional conventions in Samoa and Nauru to add provisions to the written constitutions to recognise Indigenous customary law and institutions. In Papua New Guinea, the constitutional planning committee, led by Father John Momis, took a different approach again. Momis believed that constitutions should outline “The philosophy of life by which they”, the people, “want to live and the social, economic and spiritual goals they want to achieve.”

As a result and with the help of other advisors such as Kenyan scholar, Yash Ghai and Papua New Guinean lawyer, Bernard Narokobi, Papua New Guinea’s constitution contains elements unique in the Pacific. One example is an aspirational list of national goals and directive principles and basic social obligations.

I want to end by returning to what I frame as constitution currents, this idea that constitutional texts and ideas move around the Pacific and beyond, creating complex genealogies and generating new ideas as they move and I want to suggest that this happens despite the commitment of advisors like Davidson and Lynch to short technical constitutional texts and the tendencies to assimilation that we see in the decolonisation process.

We have seen how advisors like Davidson and Lynch themselves travelled around the region from place to place and constitution making process to constitution making process. And while Lynch and Davidson have been the focus of my research here at the library, they are just two in a rather crowded field of constitutional advisors and drafters during this decolonisation wave of constitution making, which involved a host of Australian and New Zealand lawyers and academics as well as some from outside the region such as Yash Ghai and some Indigenous Pacific Islanders such as Bernard Narokobi.

We can expect that as constitutional advisors and drafters moved around, they carried ideas and innovations with them and that these ideas developed and changed in response to the particular contexts and needs of the Pacific peoples they were advising. There are a number of potential examples to demonstrate this process but I focus on just one here, which is the idea of a homegrown or autochthonous constitution.

So, we have already seen that Davidson was a champion of the idea that the people of the Pacific nation themselves should be responsible for making their own constitution. The point of setting up conventions of representatives was to create local bodies that would approve the draft constitution and bring it into law. The alternative, which was the approach taken in most British colonies in the region, was for the constitution to be drafted by British officials, in consultation with Indigenous leaders and brought into effect by British law.

Davidson and Lynch both rejected this approach. For Davidson, it was enough that a convention of Indigenous representatives approved and passed the constitution, even if that convention was a creation of colonial law and the draft was prepared by external advisors.

Lynch took things one step further in Papua New Guinea and devised a rather elaborate procedure by which the body or representatives responsible for making the constitution was not in any way a product of Australian law, that there was an absolute legal break. Lynch was also instrumental in taking the idea of a homegrown constitution seriously, not just in the procedure for making the constitution but in its substance. In other words, he engaged in a much more closely with the consequences of autochthony for the text of the constitution.

I have suggested that Davidson was sometimes a little reluctant, perhaps for good reason, for Pacific constitutions to venture too far into innovation when it came to Indigenous law and customary institutions. Lynch, perhaps inspired by that “Why not?” philosophy, was less restrained. For him, the expression “homegrown” took concrete meaning through the drafting process. This is particularly evident in the constitutional provisions about the adoption of laws and the development of the underlying law in Papua New Guinea’s constitution.

The law is complicated and I won’t bore you with the details. Simply put, for Lynch, the principle of autochthony meant that Australian law should not be given any special status in the independent state of Papua New Guinea. That said, it would not be a good idea to abandon it entirely because it would take the independent state of Papua New Guinea some time to make its own legislation and common law and we didn’t want to leave a gap in the law in the meantime.

The collection of Lynch’s papers held here at the library contains a lot of writing debating this very question. What came to be described as the Lynch approach prevailed. Lynch’s idea was to retain the Australian law that applied to the territory of Papua New Guinea. The parliament of the independent state of Papua New Guinea would of course have the power to change these laws by legislation. However, until the parliament did so, judges would be constitutionally obliged to take an innovative approach. Rather than automatically apply laws from Australia or England, judges would have to develop what Lynch called the underlying law, based on Indigenous custom as well as common law and adapted to the circumstances of Papua New Guinea.

The constitutional provisions that Lynch drafted to reflect this policy are really complex, perhaps unnecessarily so. This is about a quarter of them on the slide here. They are remarkable, however, for the attention given to the question of how to develop an autochthonous legal system and Indigenous jurisprudence and the constitutional mandate imposed on judges to take an active and transformational role in doing so.

So, these provisions for the constitution of Papua New Guinea did not travel in a cut and paste kind of way to other Pacific constitutions. However, I want to suggest that a similar concern animated the drafting of Tuvalu’s second constitution, which Lynch was also involved in. This constitution was drafted a few years after Tuvalu became independent and it replaced the independence constitution that had been made as an order in council by the British monarch in 1978.

So, in Lynch’s papers at the library is an annotated copy of Tuvalu’s independence constitution of 1978, on which Lynch has written a lot of handwritten notes, indicating which provisions he’d like to redraft and various other reflections on the text. Article 85, which is on the screen, provides that Tuvalu’s court shall apply the laws in force immediately before independence day with the power to modify such rules to take account of Tuvaluan custom and tradition. So, this is a similar idea but with less detail and direction to that taken in Papua New Guinea. Next to this provision, Lynch has written “Most unhappy.”

We have no way of knowing whether this comment reflects Lynch’s views on the drafting of this provision or the views of the Tuvaluans he was working with. He did criticise this provision in his published writing, saying that the late inclusion of the concept of custom in the constitutional text, which had been at the insistence of Tuvaluan leaders, did not allow the drafter to adapt the whole pattern of the constitution to this idea.

In Tuvalu’s second constitution, which Lynch helped to draft, the approach to the development of the law is markedly different from article 85. It is also markedly different from other constitutions in the region. Tuvalu’s constitution sets out seven constitutional principles, the majority of which emphasise the importance of Tuvaluan custom and tradition. I’ve put some examples on the slide here. For example, the sixth principle states that “The life and laws of Tuvalu should be based on respect for human dignity and on the acceptance of Tuvaluan values and culture and on respect for them.”

The constitutional principles are expressly stated to be part of the basic law of Tuvalu, from which human rights and freedoms derive and on which they are based. The text also states that the constitution shall be interpreted and applied consistently with the principles. These parts of the Tuvalu constitution show how local culture, tradition and values are expressly placed at the heart of the constitution, as the foundation to the more standard provisions for the structure of government. The constitution of Tuvalu of 1986 thus reflects, I think, John Momis’ vision of a constitution as setting out the philosophy of life by which the people want to live and their spiritual goals in particular.

One question to which Joe Lynch’s papers here at the library have unfortunately not provided a clear answer is how these principles and provisions to entrench Tuvalu in custom and tradition as the basic law were drafted and the role, if any, that Lynch had in this constitutional innovation. The principles do appear in Lynch’s drafts. These drafts do not share the same degree of technical legal language that appears in the constitution of Papua New Guinea, which might suggest Lynch was less involved.

On the other hand, it might be that his own ideas had developed over a decade of advising on constitutions across the region or that true to his calling, he was drafting constitutional provisions on instruction from Tuvaluan leaders in a way that produced a coherent constitutional structure. And while I cannot yet answer this question, I’m convinced, I hope, that my attempts to answer it will only reveal further variety in the pathways to how the constitution words.

The papers of the constitutional advisors and drafters I have examined here show that their role was not simply to devise the words for the text of a new constitution. Rather, how they went about their work was also important. Both Davidson and Lynch developed their own understandings of their role as advisors and drafters and those understandings and roles changed over time and place. I think we see Davidson as both drafter and advisor and Lynch as both drafter and advisor at certain points in their careers.

Through their relationships with the people they worked with, they were sometimes to push innovative constitutional provisions and distinctive understandings of a constitution. Their work was not simply to write and the words in the constitutions they helped to produce were not simply borrowed from somewhere else. Rather, as decolonisation progressed and progresses still, constitutional advisors and drafters faced the challenge of translating the aspirations of Pacific peoples into constitutional texts that yes, have travelled from elsewhere but in the process of drafting become homegrown. Thank you.

Libby Cass: Thank you, Anna. That was fascinating. We now have some for questions and as this presentation is being recorded, please wait for the microphone to reach you before asking your question. We might have some questions coming from online as well. They’ll be read out by my colleagues with the microphone.

Kim Rubenstein: Thank you very much, Anna. Kim Rubenstein here. I have two questions that relate to some of my own interest in this area. One is if you’ve found any women who were involved in any of these draftings and I noticed that one of the images up there with the handwriting said, “My draft for Elizabeth”, I think it said. So who was Elizabeth? My second question is in relation to that connection between Papua New Guinea and Australia. So I’ve done a lot of work on the citizenship status and I’m just wondering if you’ve seen any specific analysis of those citizenship provisions which have had dramatic ramifications for people here in Australia?

Dr Anna Dziedzic: Wonderful. Thanks so much, Kim. Yes, you reminded me that I did have a line about women and I took it out. So, Elizabeth was Lynch’s daughter and there’s some really lovely papers in his collection that say that Elizabeth must have been in primary school or something when all this was happening and Lynch actually wrote some little explainers for the primary school students about what a constitution is and how it works. Elizabeth went on to become a lawyer. So, I think I liked that image because it’s “My draft.” I think it’s one that he felt he had the most ownership of before other people got their fingers into it. But yes, there’s quite a lot of his papers dedicated to Elizabeth.

There were women drafters and I think it’s a really interesting area of inquiry. So, two that are most well-known, one is Rowena Armstrong, who worked very closely with Davidson on the constitution of Nauru. So, she was the drafter assigned by the Australian government to work with him on that constitution and there’s some really interesting parts of the debates where she’s asked to speak and you kind of see her getting a little bit mansplained at times by Davidson. That’s my interpretation at least. But I think she came to be very well respected for her views on the drafting of that constitution.

The other woman who became very much involved in drafting constitutions is Alison Quentin-Baxter. So she was involved in the Marshall Islands constitution and various other parts as well. So yes, I’d love to know about more. Both the conventions in Samoa and Nauru were definitely all male. I think possibly in PNG as well. So yes, there’s some very important avenues of inquiry in relation to gender in this whole process of constitution making.

On citizenship, there is a lot in the papers about when and how to define citizenship. It was one of the first issues that Davidson was asked to advise on to the working group and it was one of the first issues that the working group put to the people of Papua New Guinea, this sense of how do we define who we are. There were sort of two elements to that. One was how do you define Papua New Guinea against Australia and navigate the very technical rules about who was an Australian citizen at the time, which were racially defined in ways to exclude people of the territory. White Australia policy was still very much part of the story.

But the other function of citizenship laws and talking about them was to bring this kind of disparate group of peoples together. There wasn’t a sense of Papua New Guineans at the time. You were from the highlands, you were from a province, you were from a tribe, you were from a clan. So, the committee worked very hard to put citizenship front and centre in the minds of the people as well. So, there’s a lot there. Thanks.

Speaker 1: Thanks, Anna. Just on that last point of citizenship, there’s a fascinating contrast between Samoa and Papua New Guinea in as much as you would be aware, I’m sure, that Samoan provisions are much more generous or inclusive than they were in Papua New Guinea and there was a very big debate about all of that, as you’ll be aware.

My question though is I guess a comment on which you might wish to respond, concerns this concept of homegrown and you’ve addressed that in terms of meaning discussed and endorsed and finally agreed on by the population of the country through a process. But there was also that broader sense of homegrown as in reflecting traditional values and traditional customs and I think that’s what John Momis and the CPC were really very strong on and that was clearly a source of great contestation and I think that level of contestation was much higher in Papua New Guinea than it was in Samoa. I’m interested in your comments on that. Thank you.

Dr Anna Dziedzic: Thank you so much. On the citizenship point, there were actually letters between Lynch and Davidson. So, Davidson had advised on the citizenship law of Samoa, which was actually made by the constitution was put into place, in part to be able to define who could vote in the plebiscite on independence and who could vote for the parliament that would take the country into independence. So, citizenship was sort of worked out beforehand and Lynch knew that, so he wrote to Davidson and said, “How did you come up with this?” It was clearly at the top of his mind and others in Papua New Guinea at the time.

I think you’re right. I think that that meaning of homegrown is not just procedural, it’s something to do with the content of the constitution and I agree, I think it’s much more front and centre in Papua New Guinea, 10, 15 years after the Samoan process.

There’s different ways you can think about why that might be. One might be that Samoa was the very first state to do this as part of their decolonisation process and there is that sense, as I said, in the convention debates of the UN’s looking over our shoulder, we’re going to have to convince the UN that our constitution is going to work. I think one of the best ways that they thought to do that was to make a constitution that looked like other constitutions.

They did get their way on some things. So, there is no universal franchise in the Samoan constitution, in part to protect the chiefly system, which at the time was matai chief only voting. And there was a huge discussion about who should be the head of state and how should they be appointed.

So deep in the details, it’s there and I think that’s part of the broader point about how to read these constitutions. I think a lot of people just say, “Oh, this looks like any other constitution from a decolonisation context” but it’s getting into those very small details that might reveal the parts that are homegrown or are innovative.

But you’re right, in Papua New Guinea, the constitutional planning committee had a much freer rein and a much more ambitious project to make a constitution that was going to reflect Papua New Guinea and they had advisors that helped them do that. I’m not sure that Davidson would’ve been one of them but people like Yash Ghai and Bernard Narokobi certainly were on board with that kind of vision of a constitution. Thanks.

Speaker 2: Thank you. I was wondering if you had the chance or the time to look at UN archives and see how the UN reacted differently, depending on whether it was this homegrown constitution or the more western inspired constitution? That’s my first question. My second one is I’m curious about the role or the place of First Nations advisors of drafters in current processes.

Dr Anna Dziedzic: Cool. Thank you. So let me take the last one first. So I think that now today there is a lot more local ownership. So, in Bougainville and Tuvalu, the two examples I gave of processes today, yes, leaders seek advice, usually from people they trust. So Tony Regan, who some of you might know, very closely involved in Bougainville constitution making for many years, many decades. I’m sure he might be asked to provide advice.

But the whole process, which is kind of still led in a way by John Momis, who’s Bougainvillean, is very much Bougainvillean. There’s very limited outside involvement at present and the same goes for Tuvalu. They had a process, where there was quite a lot of external advisors, the UNDP provided a lot of assistance and for various reasons that process failed. So, the constitutional change wasn’t implemented.

But during COVID times, when of course the borders were shut, they had another go at it. They’ve been having meetings in Tuvaluan and it seems to all be on track and going quite well. So, I think there’s that greater sense of we know our laws, so we have the skills and we have the people to make our own laws now, so it’s a little bit different.

On your first question, remind me.

Speaker 2: UN, their reactions, like historically.

Dr Anna Dziedzic: A little bit. You can see it a little bit in the minutes of the visiting missions and so on, but my impression is that it was more a fear, it was more a concern in the back of people’s minds rather than an express requirement. Although the UN did insist upon universal suffrage for the plebiscite that would decide independence and adopt the constitution over the objections to the Samoan people and the leaders, who wanted it to be a kind of process led by the matai representatives. So yes, it’s definitely there. I haven’t done a great deal of work on the UN archives but Davidson’s papers have all of the relevant reports and everything like that, yes. I wonder too if the UN’s approach might have changed markedly since then as well.

Libby Cass: Are there any other questions from the floor or online before we wrap up? I think the pause means no. So thank you so much. As we draw to a close, just some quick plugs and thank you, Anna, that was really fascinating. I do really appreciate the investment that our philanthropists make in providing access to our collections. I live – well, I work here, I live in Canberra and I’ve just learnt so much about our collections just from being here today, so thank you.

Just a plug, if this has inspired you to become a constitutional scholar, the library has recently acquired some of the papers of the late Professor Brij Lal, who was involved in the constitutional review of Fiji, Fiji as a new government. It’s possibly going to have a new constitution, so there’s some really interesting research out there for those of you who might be inspired. Having lived through two constitutional crises in Fiji when I was living there, this was really fascinating to me, so thank you, Anna.

I hope you can join us for our next fellowship lecturer, From Shoddy to Superfine: A Material History of Australian Wool with Dr Lorinda Cramer, next Thursday, 15 June at 5.30 pm. Our website is the place where you’ll be able to find recordings of the very interesting and diverse recent talks and performances from our fellows and these are also available on our YouTube channel.

Thank you so much for attending today, those that have been here in person and those that are listening online or those that might come later because you can watch it after. Please join me once again in congratulating Dr Dziedzic for today’s fascinating presentation.

‘Pacific historians such as Tracey Banivanua Mar in her book Decolonisation and the Pacific, urge us to resist this assumption and to pay attention to the mobility and agency of Indigenous peoples across the Pacific and the diverse ways in which they advocated and practiced independence within the constraints of colonial power imbalances,’ Anna explained.

Her motivation for this research project aimed to understand where written constitutions fit into the intersection between Indigenous and Imperial relations. Anna was interested in examining the dynamics of internal and external influence that shaped constitutions in the newly independent states of the Pacific.

Most of Anna’s time during her Fellowship was spent in the Special Collections Reading Room, reading the papers of J.W. Davidson and C.J. Lynch, two extraordinary minds whose works provided advice on independence constitution-making across seven Pacific countries from the 1960s to 1980s. Their papers included draft constitutions, records of consultations with communities and debates of constitution-making assemblies, legal advice on questions of constitutional design and how to manage the legal transition from colony to independent statehood, lectures, along with correspondence with officials, academics and lawyers across the region.

‘I was surprised - although perhaps I shouldn’t have been - at how many of the constitutional issues that Davidson and Lynch were dealing with are still issues today,’ said Anna.

Values and Principles

One of Anna’s most interesting discoveries was in Lynch’s papers. Lynch was engaged as a constitutional adviser to Tuvalu - a rare example of a Pacific nation that was not content to keep the Constitution which was made upon independence by imperial order of the British monarch. A few years after independence, it embarked on a process to make a new Constitution, that better expressed the values and principles of Tuvaluan government and society.

Although he passed away before the new Constitution of Tuvalu came into force in 1986, Lynch’s collection of materials included the minutes, covered with handwritten notes and annotations of public consultations on each of the islands of Tuvalu, as well as professional groups in the capital Funafuti.

‘These notes provide a fascinating insight into what the people of Tuvalu wanted from their Constitution, and how these aspirations were translated by Lynch into the legal text of the Constitution,’ Anna added.

Anna is currently working on a book chapter on ‘multitasked’ office in small states. Her work is inspired by CJ Lynch’s advice on the dual head of state and head of government in Marshall Islands and Kiribati, and Davidson’s constitutional advice in Nauru. She is also writing an article on the connections between the constitution making ‘waves’ in Oceania, from the 19th century to today.

Anna has recently begun a new role with the International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (International IDEA), where she will be working as a Program Officer for Constitution Building Processes in Asia and the Pacific.

National Library Fellowship – Inspiring new avenues

‘The NLA Fellowship has been an incredibly rich and rewarding experience, inspiring new avenues for academic research and writing‘, Anna said, on being asked about her experience with the National Library’s Fellowship program.

‘It is a rare thing in academia to be granted significant time to devote to exploring a collection of papers, without the pressures of a specific grant proposal or particular output in mind. This is what the Fellowship offers - time, together with a beautiful space to work, access to a diverse and rich collection, and expert support and advice from NLA library staff.’

Read more about the National Library’s Fellowship and Scholarship programs.