Known as a pioneer of expressive dance, Gertrud Bodenwieser’s fascinating career had a great impact on Austrian and Australian modern dance. For those unfamiliar with her work, as Dr Wesley Lim was previously, one of the best and most accessible ways of exploring her choreography and movement styles is through photographs of her and her dancers.

These photographs, however, led to more questions for Wesley: Who were the photographers who shot these images? How did they work with the dancers to capture their movement? What stories do the resulting photos tell and what do they reveal about the history and aesthetics of dance photography?

Following his years of work in German, dance, performance and screen studies, it was these photographs that became the focus of Wesley’s 2023 National Library Fellowship.

How it all began

It wasn’t until Wesley moved to Canberra in 2018 that he learnt of Gertrud Bodenwieser’s work, following his discovery of her papers here at the Library.

‘As an often-forgotten contributor to modern dance, her archive surprisingly holds quite a vast and detailed collection ... I was immediately drawn to the photographs because of the sheer number and the stories that they could tell,’ he explained.

From there, Wesley set out to view, categorise and analyse these hundreds of photographs, as well as the key photographers involved.

Behind the camera

One photographer soon emerged as ‘another protagonist in the story’ that Wesley was telling: Margaret Michaelis. In addition to the captivating photos their collaborations created, Michaelis and Bodenwieser shared a very similar history; with them both having grown up in Austrian Jewish families, and then having to leave their established careers in Europe to come to Australia in the late 1930s.

It was a series of photographs by Michaelis featuring two of Bodenwieser’s dancers, Hilary Napier and Shona Dunlop, that Wesley found to be particularly noteworthy. This is in part because these photographs were taken at Palm Beach, New South Wales, rather than inside a studio. This environment and the effect the wind had on the dresses worn by the dancers resulted in some stunning images that Wesley analysed in his fellowship presentation.

Kathryn Favelle: Hello everyone and welcome to the National Library of Australia. My name is Kathryn Favelle. I'm Director of Reader Services and one of the joys of my job is that I get to have oversight of the Library's Fellowships and Scholarships program. As we begin our first event of 2024, I acknowledge Australia's First Nations peoples as Traditional Owners and Custodians of the land on which the Library stands and from where you are all watching tonight. I also give my respect to Elders past and present and through them to all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

Thank you for joining us. It's so wonderful to start the year with a good and chatty crowd. And I know that tonight's presentation is going to be engaging and stimulating and add to the conversations that you've all been having. I'm especially delighted that our first event is showcasing the research of one of the National Library's Fellows. Call me biased, but I am. Our distinguished Fellowships program supports researchers to make intensive use of the National Library's rich collections through residencies of up to three months. The program in turn is supported by generous philanthropic gifts, large and small, from an extraordinary group of donors. And I'd like to thank those donors for recognising the benefits that come from the time to research deeply and for support, for supporting scholars to explore our extraordinary collections.

This presentation, "Staging Nationhood in Dance Photographs" is by Dr Wesley Lim, one of our 2023 National Library of Australia Fellows. Dr Lim is a German Studies scholar with expertise in dance, performance and screen studies. He received his PhD in German literature from Vanderbilt University in 2012 and is himself a former dancer. He's currently a lecturer in German studies at the Australian National University. During his Fellowship at the Library, Dr Lim has delved into the papers and photographs of one of the legends of Australian dance, Gertrud Bodenwieser. And I know from the conversations I've been hearing that many of you here tonight have your own stories about Gertrud Bodenwieser and her influence on your life and your dance practise. Please join me, though, in welcoming Dr Wesley Lim to share with us what he's found in the collections.

Wesley Lim: Hi, thank you for coming. I would also like to begin by acknowledging the traditional custodians of the land on which we gather and pay my respects to Elders past and present. And thank you to the Fellowship team at the National Library, Sharyn, Simone, Gemma, and the other Fellows for being so welcoming and imparting so much knowledge on me.

This larger project deals with the photographs of Gertrud Bodenwieser and her dancers, which are housed at the National Library. It also looks at the further print culture involving these photographs in posters, programs and magazines. However, the talk today will focus mainly on the photographs.

When I applied for the Fellowship last year, only a handful of the images had been digitised. I would say this is not an atypical practise as many archives do not digitise everything, but instead have researchers come in to look at the material. And also because it is, it's a lot of work to digitise photographs. However, to my surprise, due to generous funding from the Dick and Pip Smith Foundation, a large part of this collection had been digitised in 2022, which I am eternally grateful for. And I hope this will allow dancers and researchers from various disciplines to analyse these materials regardless of their geographical location. Part of what I've been doing during my research is organising these photographs, so I've counted 400- over 410 digitised photographs, and many of these are also in other related collections that have not been digitised, for example, personal scrapbooks. So there's a lot of other materials here that I was not able to go through that relate to this collection as well, but have not been digitised.

To give you some background on myself and how I came interested in these photographs, my training is in German studies, which encompasses a combination of literary studies, cultural studies and critical theory. On top of this, I specialise in dance and performance studies. However, I read widely and have realised that through my research at the NLA that there will need to be larger and more developed strands of photography, scholarship, and Australian studies scholarship as here as well.

In my studies of dance and education, Bodenwieser did not come up often. Originally from the United States, it wasn't until I moved to Canberra to work as a lecturer in German studies at the ANU in 2018 that I realised that the papers of Gertrud Bodenwieser were at the NLA. Since I was not familiar with her choreography and movement style, my access visually was through photography. I was immediately drawn to the photographs and the number available. Two of Bodenwieser dancers, Marie Cuckson and Emmy Towsey, have provided meticulous documentation of the photographs that in a sense provide a history of dance photography practises in Austria- in Australia that can be told.

I've always been interested in looking at the, I'm also interested in looking at the posters and programs and photographs used in print material, in magazines like "Pix", but research on that will be at a later stage.

I've also been thankful to listening to "Keep Dancing", an oral history project that has given a rich number of histories of dancers in the Bodenwieser company among other artists. This was and continues to be done by Michelle Potter.

As much as I was drawn to these images, I realised there was an enormous amount of information I didn't know. Who was Bodenwieser, what was her choreographic and pedagogical style like, and who were the many photographers who shot these images and what are their stories? The archivist, Cuckson and Towsey have compiled a catalogued list of photographers who each took photographs of Bodenwieser and documents when and where these were taken. So as you can see from the list, this list that I've compiled, so Dora Kallmus, also called D'Ora, was an influential fashion photographer in Vienna, and also worked with another photographer for about a year named Margaret Michaelis, who I'll engage with particularly today. Many of you might be familiar with Max Dupain and some of his work, Noel Rubie, Bill Brindle and S. P. Andrews. And as I said, I'll focus on Margaret Michaelis today.

From what I've seen in the collection, most of the photographs in the archive are taken in a studio setting and are extracts from dance choreography, but some of them are taken outside. And this particularly- this interests me particularly and these are the ones that we'll be looking at today.

My broader project is to discuss these images as being hybrid collaborations between the photographer and the Bodenwieser-trained dancers, and to what extent nationhood through Austria and Australia come through in these photographs. And all this work will culminate, hopefully, in a larger book project.

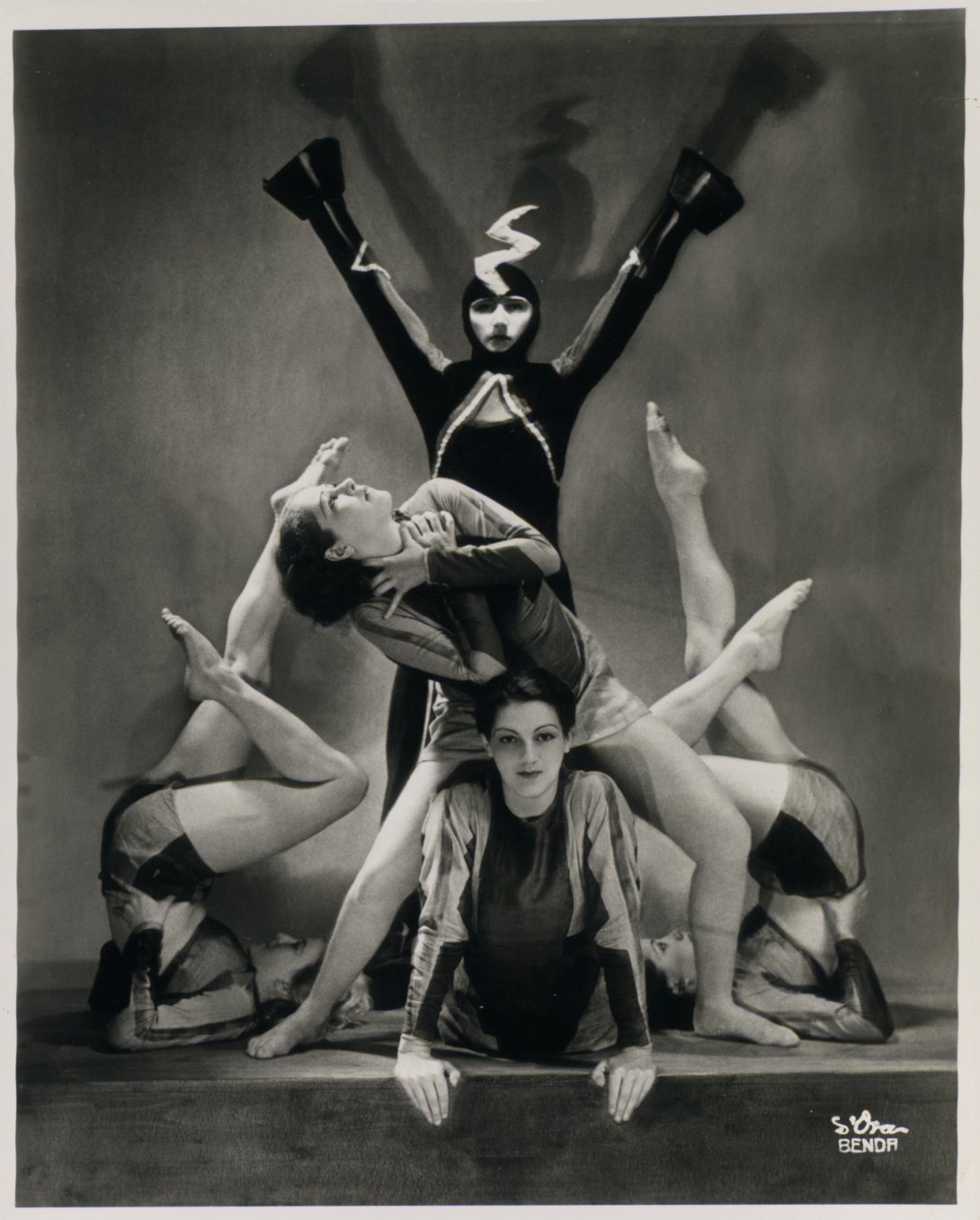

So before I get into the analysis, I'll give you some background information and a short biography of Bodenwieser if you're not familiar with her. And you can see in this image, this is from a dance called "Spanish Dance" that she did. Probably the highlight of this is this bending position that you'll probably see in most of her choreography. And a lot of her dancers will take on in their own bodies.

So Gertrud Bodenwieser was born on the 3rd of February, 1890 in Vienna into a bourgeois Jewish family and was exposed to German culture and arts at a young age. She began taking ballet classes with Carl Godlewski at the Vienna State Opera, but soon became more interested in expressive dance. She felt ballet was from another time, with its pointe shoes, corsets and fairytale plots, and these could no longer express what people around 1900 were experiencing: a return to nature, battling with technological developments and urban life. Thus, she turned to barefoot dancing, creativity and movements that could express these emotions. She wanted dance to be intellectual. She wanted it to say something, as she says, and, "To reveal the whole gamut of human feeling." Bodenwieser states, "We should give people not what they want, but what they need. We need modern dance", which I find I find very provocative and quite interesting. And this came from "The New Dance" that she's quoted from.

Influenced by the intellectual scene in Vienna, by authors like and intellectuals like Arthur Schnitzler, Thomas Mann, Stefan Zweig, Hugo von Hofmannsthal and Max Reinhardt, she married Friedrich Rosenthal, artistic director for first the Volktheater and then the Burgtheater in Vienna. This connection put her in constant contact with other artists and patrons of the arts. The painters from the Hagenbund allowed her to have her first dance debut in a private chamber performance by invitation only. And you can see that here. This was her big break.

She began the Tanzgruppe Bodenwieser in 1923 and danced extensively throughout Central Europe. However, when Hitler began the Anschluss of Austria in 1938, Bodenwieser knew it was time to go. She sought- she temporarily sought refuge in Colombia, touring there for 10 months, before deciding to come to Sydney, joining some of her dancers, and began modern dance practises. She started the Bodenwieser Ballet and toured extensively throughout Australia, even to regional and bush towns. She never returned to Austria and never had children.

I'll also give you some background on Margaret Michaelis. So another protagonist in the story today is a photographer who shot images of Bodenwieser. Michaelis was born in 1902 in an Austrio-Hungarian borderland and grew up in an educated Jewish bourgeois household. She moved to Vienna to learn photography in 1918 and attended an institute that only recently allowed women to enter. For nine months, she worked in the Atelier D'Ora, Dora Kallmus, a prominent Jewish photographer of fashion, portraits and dance. She later maintained a peripatetic existence working in Berlin at various studios. While she proclaimed her love for dance in letters, she never portrayed the form seriously until moving to Australia. Before moving to Sydney, she spent four years in Barcelona and took many urban images and photographs of daily life during the Spanish Civil War, and opened her first studio to gain a sense of autonomy.

When she moved to Sydney, she didn't know anyone, unlike Bodenwieser, who knew some dancers. Unlike in Europe where women photographers are making a name for themselves and had opened their own studios, it was difficult for her to find work in a male-dominated photography workspace in Australia. So Michaelis opened up her own studio, focused on, focusing on portraiture, which was still in demand at the time, and which she enjoyed doing. Working from 1940 to 1952, she focused on émigré, her energies on photographing the arts and portraits of European and Jewish émigrés. She grew to adore the Australian landscape.

So as you can see, as both Michaelis and Bodenwieser were Austrian, Jewish exiles, and they were both women who arrived in Australia around the same time and they ran more or less in similar émigré circles. And they also had a similar modernist sensibility in their work. In essence, these synergies can be seen in their work by working together.

Bodenwieser's style can be characterised as between classical ballet and Mary Wigman's expressionist dance style, a German strand of expressionist dance. Her dancers were able to perform soft, swinging and jovial movements, as we see here, as well as grim, dismal, mechanical themes. So in essence, a very broad range if you compare that to the work of Mary Wigman. So here you can see some of her students in Vienna. And this dance would, I would get hazard to guess is probably the most famous because it's, I've seen so many renditions of this. And if you are a dancer yourself that danced this technique, then you may have either heard of this or maybe even danced a reconstruction of this. So, I'm not talking about this today as much, but this is one of the dances that you might be familiar with. And just to give you a sense of their style, of her style.

Toward the end of her life, Bodenwieser wrote a large part of a manifesto called "The New Dance" in 1959 with the help of Marie Cuckson. It traces her philosophical inspirations for movement. She lists the names of Rudolf von Laban, who made her aware of spatial awareness and its planes. And as you can see here, this is an icosahedron and this is a live, oops, let's see. It's kind of a, as large as, kind of reminds me of something that we see on a playground, right? But it's essentially a 20-sided die. And these are the ways that you could kind of figure out where you were in space and the different kind of, kinds of planes that were available to you. And Laban also invented dance notation, or he calls it Laban notation, that the demon dance, the "Demon Machine" was also based.

Bess Mensendieck made Bodenwieser aware of posture and awareness of physiology, giving them, giving her dancers also this awareness of how the body works, 'cause she felt that was quite important.

And Émile Jacques-Dalcroze made her quite aware of musical expressivity. So, most of her dances were also done to music. This was in opposition to, for example, Mary Wigman, who ended up mostly dancing to percussive instruments or in silence, so these were some of the differences that were happening in modern dance.

And François Delsarte, who was made Bodenwieser aware of this physio-psychological link to movement through sculpture. Yeah, laws of opposition and this natural succession.

One of Bodenwieser's Viennese dancers, Hanny Kolm Exiner, describes what happened during a typical class. So, "Bodenwieser's style reflected her personality, impulsive, dramatic. She favoured circles, waves, figures of eights, spirals. Her movements were strong but not sharp, gentle but not sweet. They were full of dynamic impulses and free flowing, yet at every moment the dance pattern produced a satisfying sculptural effect. There was much use of the floor level, of high leaps, of powerful leg movements and whirling turns as well as the most delicate and sensitive hand gestures, head and torso." Bodenwieser's classes were also a mix of expressionist dance or expressive dance, gymnastics, classical ballet, spring class, acrobatics and tap.

So on top of this, they also, they had classes in the history of dance, the history of art and the history of costume. So for me, this seems relatively kind of holistic education and I believe influenced a lot of how dance curricula is formed today. In fact, these are some of the classes I took for my dance minor, so this might also be happening in an Australian context.

So barre often opened up the class, more for warming up than an actual ballet barre. And I, what I've read is also this happened in a circle as well. This trains them not to also to focus on looking at poses of themselves in the mirror. This would be more of a ballet type of aesthetic. And they would work with one theme of the day and build on it throughout the class. They would also do this in a Labanesque fashion using different variations, by doing movement combinations at differing speeds, differing levels, and with different stresses. The last and probably most loved activity happened at the end of class when they all did an improvisation. And she never gave a pure technique class. This was also very much focused on the students' experience and the students' experience with each other.

Let's see, according to Alys George, "Free dance and Ausdruckstanz had achieved such a high level of estimation in Viennese cultural life that official, even political ceremonies and celebrations in the late 1920s and early 1930s frequently included a requisite modern dance performance by Bodenwieser and others." So this gives you a sense of how high and how important such kind of events were.

Carol Brown talks about how such a wide range of pedagogical methods brought agency into their dance and made them aware of their political, socio and political settings. As many have argued, "The Mask of Lucifer", one of her dances, for example, anticipated the coming of Hitler. Unlike Hitler, sorry, unlike dancers like Laban and Mary Wigman, who allowed themselves to be swept up and instrumentalized by the Nazis, by changing their Weimar-era expressions choreography to now fulfil a National Socialist ideology, Bodenwieser completely resisted, left Austria, went into exile in Australia, and this was reflected in her choreography, particularly in her dance dramas.

Through the eyes of Brown, I believe Bodenwieser's dance practises taught her company dancers and students about ethics, social and political awareness, interpersonal relationships, respect through dance and somatic practises. Somatic practises being awareness and awareness of the health of your own body. If I were to give you another example, if you can think of, if any of you do yoga or meditation, I would say this is a form of somatic reflection. And unlike the practises of American modern dance, which focused on technique, Bodenwieser's practise highlighted autonomy and somatic practises through improvisation.

So besides "Demon Machine", which I showed you earlier, you might be aware of Bodenwieser's renditions of different Viennese waltzes. So these are movements that would involve curving, swinging, flowing, bending, bouncing and gliding. And just a quick note before I continue. What I like and why I've chosen these two images was the first one reminds me of pure motion and the fact that the photographer was interested in capturing whatever kind of motion was going on, 'cause in the first one, the faces are kind of obscured. It looks like you might be in the wings, people aren't positioned in the correct way in which there'd be this kind of human, more human interaction. Whilst you look in the second one, this clearly says, and you can see here it says, "Pose", that this was posed for the camera. Everyone is facing in one direction. Everyone gets a similar amount of attention. And so these, probably something that I should investigate, the difference between how these dancers were photographed, and under what conditions.

So in regard to the photographs of Bodenwieser's waltzes that we just saw earlier, she was likely inspired by another Viennese modern dancer named Grete Wiesenthal, who became famous for her variations on the waltz and whose Strauss theme became the unofficial Austrian national anthem. Considered a national treasure, the Austrian author Hugo von Hofmannsthal also commented on the Heimat-like and folkish mystery of Wiesenthal's dances. These found performative representation, Wiesenthal's spherical dance, which according to Alys George, "The momentum and seemingly anti-gravitational quality of the leaps and spins, the spatial physicality and perform, and powerfully expressive motions of Wiesenthal's dancing, her swirling circles were not only revolutions in the literal sense, but also revolutionary contributions to free dance in Vienna."

Wiesenthal describes that the most difficult element in her dances are, "To achieve the most stability possible in the body's greatest possible extension and reach to all sides." So this is something I found very similar also in Bodenwieser's dancing.

And Gabriele Brandstetter finds that this loss of control and spatial orientation as intoxicating and creating freedom whilst being carefully staged. And we obviously see these in Bodenwieser's dancers.

Okay, so let's see. So reminding one of this organic, natural and feminine iconography would probably be Jugendstil, or art nouveau, which you might be familiar with. And you can see two images here. This is by- the one on the left is by Otto Eckmann, and this is the cover of a literary and artistic magazine called "Jugend". And you can see flowers on her hair, but also in the background. You can see this is also done in profile, and the hair also has this waviness that's overcome. And in a second image, "Der Kuss" or "The Kiss" by Peter Behrens, similar kinds of iconography as well. Probably the hair in this one I found was really amazing and kind of overwhelming for the senses as well, yeah.

I'll chat a little bit now about the dance photography and how I'm kind of viewing all of that. Photographs of dancers such as Bodenwieser's dancers functioned as a glamorising promotional and documentary tool available for circulation, movement and image literacy. This is according to Matthew Reason. The raison d'être of these photographs was publicity for the dancer, the company and Bodenwieser in newspapers, magazines and performance programs.

Karl Toepfer alludes to the ubiquitous nature and agency of these images, which themselves stimulate a powerful performative energy. He maintains that images of dancers in motion in the 1920s increased the public's enthusiasm for dance since they, "provided greater access to the spirit of the dancing body than concert performance permitted." And that actually, when I read it, I had to read that again 'cause I was like, how is that possible, that a photograph is actually more powerful than the actual performance? I found that quite astounding. Often the case, one is, one is unable, in case one is unable to come to these performances. "The New York Times" dance critic John Martin writes in 1929 about how dance images had crossed the Atlantic, whetting his appetite before European dancers came.

We see here an anticipation, the conspicuous and perhaps paradoxical nature of photography, which focuses on stillness, as representing dance, typically characterises movement, draws from the beginning of the 19th century where photography was concerned with capturing movement as a source of authenticity and realism. According to Susan Sontag, photographs are perhaps more memorable than video and film because they provide certain stable images that highlight a movement that can be easily retrieved from the viewer's imagination. She writes, "Photographs may be more memorable than moving images because they're a neat slice of time, not a flow. Television is a stream of under selected images, each of which cancels its predecessor. Each photograph is a privileged moment, turning into a slim object that one can keep and look at again."

Drawing from these observations, Matthew Reason argues that the particular staging of dance photographs can create a feeling of, a feel of movement regardless of static representation. He explores the photographer's subjectivity and agency in their shot selection and their roles in situating the positioning of dancers using "conscious artfulness" as a kind of manipulated staging as invented for the camera. We will see how this happens in the photographs of Michaelis.

So even before Michaelis focused mostly on portraits when she was in Australia, some of the principles between photographer and subject would carry on into her dance photography. As Helen Ennis writes, "A successful outcome is so dependent on the chemistry between photographer and subject." Either for personal reasons or public purposes, Michaelis took her portraits primarily in her studio, focusing on the individuality of the person with a neutral background and attempted to create "a modernist ethos and evoke her interest in psychology." She, like Bodenwieser, believed that outer expression revealed an inner truth, which drew from her years in Vienna and exposure to psychoanalysis.

Michaelis believed a successful portrait depended on the subject recognising the seriousness of the photo shoot as well. Michaelis believed that photography was not just art for publicity and advertising. Jan Poddebsky describes "how much mental, imaginative preparation Michaelis employed and recommended before shooting a picture. She referred firstly to the choice of subject, then choice of light, of angle, lighting and composition to convey the impression chosen. This suggests that the image already exists in the photographer's mind. She lingered on the choice of subject and discloses the pleasure of transforming an accidental or ordinary or even ugly subject into something interesting and surprising." And I find that last sentence is basically the key of what modernism is, I think to a lot of people, so I love that. So this is reminiscent of urban photography that she took in Barcelona too, where she had very little setup time, was very spontaneous.

For most of the Bodenwieser images that you've seen in this presentation and the ones in the archive, "Bodenwieser was present at photographic shoots commissioned for publicity and tours and programs. Without a doubt, her presence influenced the dancers, thus influencing some of the dancers' decisions." However, Bodenwieser was not at this shoot of the images that I'll show you with Hilary Napier and Shona Dunlop, which implies that they had far more autonomy than before. According to Shona, "She, Bodenwieser, never adapted to the Australian outdoor lifestyle and retained a horror of picnics, boiling billies. Mosquitoes, ants, and all creepy crawlies of the Australian bush." Certainly a far cry from Viennese houses, cafe houses, sorry. Yeah, I actually had to look up what boiling billies were. And so I'm better for that as an American, okay.

Poddebsky notes that "sometimes the dancers provided movement inspired by their training from Bodenwieser, thus revealing something of her movement style, and sometimes inspired by the location or situation of the photo shoots." These images are shot on Palm Beach, New South Wales, near Shona's home. Both of these dancers trained in Vienna, in Bodenwieser's school, and then later in her company in Australia. Shona was originally from New Zealand and Hilary was from the UK. These images do not come from a specific Bodenwieser work, but the style is certainly drawn from.

So the next image is not an image, it's actually a description of an image. And because I was unable to obtain the rights, this was my attempt, slightly experimental attempt. At describing how this image was, would look without infringing on copyright. So very clearly, and I'll go through this and you can look at this and you can kind of have an imagine, have this run in your imagination how this would look like, and then perhaps see the original at some point. So in this first image we see, not really, two figures, Shona on the left and Hilary on the right. They seem to be perched on a slight incline so that the beach takes up nearly half of the image and the rest is enveloped by the sky. Around the two is sand and small patches of grass peeking through. The groundedness of modern dance is even more pronounced here since they sink into the sand, becoming even more integrated with the Earth, which I love. And this was an opposition to the floating nature of ballerinas and pointe shoes. Shona has her back to the camera, but at an angle and almost in a B+ position with both of their arms, both of her arms behind her back at a 90 degree angle. Her head is pointed to the right and tilted slightly and her eyes closed and her hair flows along the back of her upper back. Hilary faces more toward the camera, but also in profile, closed eyes and slightly hinged at the waist to be tilted back. Her arms may be crossed in front of her, but the diaphanous dress obscures this.

Both appear to be in a meditative or contemplative state. The diaphanous dresses both show and obscure parts of their body, and one has the, one has to concentrate to ascertain this. These characteristics create a sculptural effect and reflect a calm beach feeling. One could also say they reflect the organic Australian nature of their surroundings with the rippling patterns of their skirts reflecting the curves of waves or rolling beach dunes. The focus on the closed eyes draws them away from the humanness and closer to nature. They also certainly evoke the Jugendstil iconography, particularly of the stationary, sensual woman, not just in Vienna but all over Europe.

And I will stop teasing you now and show you an image. The next three images appear to be a development or certainly in movement from the first. The second image seen here shows both being less static by engaging with their whole body more, limbs, chest, back, and legs and head. On the left is Hilary in almost a first arabesque pose, tilted upward with her, with chest and head oriented toward the sky. Part of her cape is attached to her wrist so as to create the impression of an extra appendage or even wing. The orientation of the camera has changed now to face the ocean and sky. Her stance announces a regal presence and the wind activates her dress to begin fluttering along with her hair. Shona, on the right, seems more sunken into the sand and is positioned slowly, slightly lower, to the right of Hilary. Instead of looking up, she looks down toward the left with the wind actively moving her hair and dress.

These images more clearly demonstrate the lack of straight lines of all of their bodies and evokes swirling nature of Jugendstil aesthetics. Not only are the arms, torso and legs all curved, but Shona is also spiraling to the right. Their heads are more active, however, and the focus of the image is on the wind activating the flowing dresses their extended, twisted limbs.

So in the third image, the dress in the air highlights a majority of the visual stimuli. Hilary stands in a similar area as the first image with her legs firmly planted into the sand on a slight incline. Her upper body arches back with her head tilted back and her face conveys a joyous, effervescent feeling with her mouth slightly open, as if taking a deep breath. We clearly see her left arm outstretched.

The bottom half of the skirt flows and we see ripples and the top of the cape is actively engaged with the air. This type of photograph would not be possible in an interior studio, lacking any kind of active air movement, unless the dancer manipulated the costume. However, here the air acts as an active choreographic entity, just like Hilary and Michaelis staging the photograph. The air activates the long strands of fabric while the photograph freezes these moments. Similar to the first image in which the tilted head and closed eyes reflects- creates a relaxed, meditative feeling, the dress and its appendages take over life of this photograph and the air brings the drapery more into an organic realm of nature.

This last image highlights different levels and curves. On the lower level of an incline in the sand is Shona in the backbend position, with arms extended, hair flowing, and the position of her legs remains obscured by the dress. Hilary is at the top right, perhaps on a ridge, bending from torso to the right with her arms outstretched to the left. They seem to touch hands and demonstrate harmonious yet asymmetrical image.

The backbend position of these images, but particularly with the Viennese waltz images, are reminiscent according to dance studies scholar Gabriele Brandstetter of the maenad, the female follower of Dionysus, the god of wine and pleasure. The maenads were characterised through their uncontrollable hysteria, their unleashing of unknown forces and their feminine irrationality. They were often depicted on Greek vases in a backbend position, streaming hair and flowing garments with an ecstatic look. We can see these backbend movements in the work of many of different, many different dancers around 1900 like Isadora Duncan, Ruth St. Denis, Grete Wiesenthal, Rosalia Chladek, Mary Wigman and Gertrud Bodenwieser, as we see here on the right. Michaelis adapted these movements. Adaptation of these movements has certainly been modified. There is a release and a joy of emotion, however, not uncontrollable, which may also correspond to the natural ebb and flow of the sea and the swirling patterns of airflow. There can be a tumultuous moment. However, they are cyclical and will return to a normal rhythm.

Michaelis may also be drawing slightly from the imagery of the American dancer, Loie Fuller, who performed all over Europe at the turn of the 20th century. Fuller was known for her skirt dances in which she manipulated large, billowing fabric around herself to morph into a desexualized, organic piece of sonography. Often only her head was seen, while the high- while the highlight was the perpetually swirling pattern of the fabric.

Hilary and Shona from the other images that I've shown you also seemed to be part of the Australian landscape. However, less through, less than Fuller, since their limbs are still recognisable. At the same time, the dresses still obscure this view.

So I'll have, I'll show you the three that I may have available. So Michaelis' four photographs seem to bring together the organic and swirling aesthetic of a European Jugendstil, Viennese waltz, the unleashing of either conscious or unconscious desires, female liberation from ballet and the corset. These qualities are not just embedded in the Australian landscape, but become enveloped with it, so much so that the dancers and costuming seemingly and in a modernist lens seem to blend into its surroundings. In many ways, they seem to create an Australian brand of Jugendstil or the Viennese waltz, heavily influenced by the Bodenwieser organic aesthetic of curves, swirls, spiraling, with the dancers in real nature instead of imagined one through drawings, furniture, sculpture and architecture or traditional theatre space.

While shot in the 1940s, Michaelis drew inspiration from the flowing dresses, curved and sweeping dance movements with rolling sand dunes and waves from the beach into a cohesive whole, melding her Austrian heritage with her new homeland. By actively engaging with the wind as a choreographer, the dresses are enlivened with a dynamic energy and appear to be flowing appendages, taking the dancer, Hilary, into a more organic realm.

In comparison with other dance images in the archive, I feel not only the combination of hybridity of Austria and Australia shine through, but the activeness of these images to be overwhelming and clearly bias the mere poses of many of the other images for the camera in the studio. This is not to say that the other dance photographs of Bodenwieser dancers in the studio by other photographers do not relay the dynamic and technique of Bodenwieser's style. But Michaelis' images communicate them very well and demonstrate the autonomy of Shona and Hilary, something that Bodenwieser staunchly stood by, the development and creativity of the individual. Something about the outside enlivens the entire collaboration, collaborative enterprise of dance photography. And that's one of the interesting things I read, particularly in an interview with Shona, was that Bodenwieser was very interested in the development of the individual's own intellect, in creating their own kind of dance and their own dance form. So when I think about how it might be considered a little bit naughty if you went off and did a photo shoot and said you're a Bodenwieser dancer, even though Bodenwieser was not there, but I think she would actually say, "No, that's actually good that they're actually doing this." And a lot of her other dancers have these, had these kind of offshoot careers, which I find really interesting as well. And didn't feel like in some ways with other kinds of modernist dance that they had to always in a kind of strange fashion to give praise and to always be- what's the word? Kind of idealistic about Bodenwieser. I think they also felt that they could also do their own thing, and I really appreciate that.

So according to Helen Ennis, "It was inescapable. It was the inescapable realities of exile and relocation that gave her portraiture and dance photographs its particularly inflexion." Unlike Australian-born photographers like Max Dupain and Olive Cotton, "Michaelis' practises did not proceed with a deep-rooted sense of home, place or nation. Instead, her photographs are distinguished by a quality of un-homeliness that has parallels in the works of other émigré photographers, notably and Newton, whose images could have been produced anywhere in the developed world." Through this émigré view, Michaelis "reshaped notions of modern photography in Australia, making them richer and far more complex." And as Poddebsky notices, "the choice to concentrate on dance photography along with portraiture for Michaelis' work in Sydney is bound up in her story as an émigré to a foreign land." Ennis also states, "Her dance photographs are effectively her passage into another world where she could let herself go, reveling in the dancers' extremes of movement and their expressive intensity. This may well explain why some of Michaelis' most memorable photographs were taken at the moment when the dancers were, are airborne, suspended improbably and exuberantly in the sky. Dance photography also offers Michaelis the possibility of dealing with rapture, capturing dancers in a state of self-absorption and all immersion in their extravagant actions."

So, and I would build on Ennis's idea by stating that this kind of other world was necessary for her to carve out in order to establish a new kind of hybrid identity. This was also the case with Bodenwieser, who struggled with it was, to live in Australia as one of those quotes had to do with not liking to be in the outside. And in many ways, Bodenwieser was also very content in the studio creating her dances, which became her own world. I'll skip that.

And according to Shona, this is one of the dancers that was in one of the four images, "The keine kultur or no culture syndrome, which Bodenwieser bemoaned so much in the beginning did not alter very much, but she learned to keep it to herself, or at least within her own circles of continental friends. Some may have considered her an intellectual snob." Yeah, Bodenwieser called Australia, "a beautiful cultural desert." Which may sound negative, and I'm interested to hear from the Australians here. That seems to be a kind of trope and I'm very unfamiliar with that and maybe I need to do my own homework more about Australian culture of what that means. However, I believe this kind of formulation is also very Australian, and you can correct me if I'm, if you think I'm wrong, dealing with a new environment, this pioneering attitude to mold things to one's desires and to fit the function of the cultural environment. And Shona also states, "Only after a few years had passed, when some of the original Australian dancers replaced some of the Viennese-trained ones in the ballet did Bodenwieser successfully begin to create an indigenous and more robust, earthy style. The harshness of the Australian landscape and the scarcity of the people in the outback took time to make their imprint on, upon her."

I'm coming to an end now. I like to think that these four images from "Sea Study" and "The Encounter" represent a hybridised version of many personal voices and influences. We see the movement style of Bodenwieser, who drew inspiration from the organic and swirling aesthetic of a European Jugendstil, Viennese waltz, the unleashing of either unconscious or conscious desires, female liberation from the ballet and the corset. Yet there are- but these are expressed through autonomous bodies of Hilary and Shona, away from their dance master, who carry their own nationalities and their own experiences. Furthermore, these swirling qualities are not just embedded in the Australian beach landscape, but becomes enveloped with it, so much so that the dancers and the costuming seemingly and in a modernist lens blend into their surroundings. Michaelis exercises her meshing of various immigrant experiences by seemingly adapting the flowing and swinging nature of a waltz-like, Bodenwieser-quality movements with the organic nature of an Australian beach. By adapting these into these photographs, this helps her and presumably Bodenwieser adapt to their new homeland without forgetting the importance and roots of their Austrian past. Thank you.

Kathryn Favelle: Thank you so much, Wesley. I'm very, very grateful that you didn't ask any of us to recreate that missing image. There was a brief moment where I thought maybe you were going to pick someone from the audience to.

Wesley Lim: Oh, I really could have.

Kathryn Favelle: I know.

Wesley Lim: A little bit out of my own dance practise, but it was, it would not be out of character.

Kathryn Favelle: We've got time for some questions, so if anyone has a question, please raise your hand. We are streaming and recording this presentation, so we want to get your question on the record as well. And we'll get a microphone to you. So give a wave if we've got one down here and Sharyn will bring you a microphone.

Audience member 1: Thank you, that was so interesting. I know you are focusing on photography, but does any film exist? Have you seen, yeah?

Wesley Lim: Oh yeah, great question. Yeah, no, that was actually one of the things that I, when I was looking at this, and it wasn't just the photographs I was looking at 'cause I, you look at the photographs and they do give you an inkling of how the motion and the efforts would be going on. But then as I went through a lot of this, I was like, there has to be something because I can't just write about something that I haven't seen. So it has to at least be mediated through a way, and at the National Sound and Film Archive, luckily they had lots of interesting things that ABC had done their own filming. It was also the Australian Ballet, it was a whole large thing, which was fabulous. And there were in, there was also the "Errand of the Maze", which came later, in the '50s I think. And then there was a bunch of other stuff that was filmed by Barbara Cookson and this was in the '70s and '71. And it has this glorious kind of like '70s aesthetic that I really want to go back to 'cause it's like watching the dances that were originally choreographed in the '40s or even before. And you see basically there's a, these blonde, Australian girls with like what I would picture as being like hair that came from the '70s. And it kind of seems transposed into a different kind of setting. But these, this is the way that I was able to actually look at choreography again without having to go through, you know, going through someone, another dancer to tell me how that was, yeah, yeah.

Kathryn Favelle: Gentlemen in the middle, there.

Audience member 2: Thank you, Wesley. Thank you so much for wonderful presentation. I'm not a dancer like you or my wife, but I'm very curious to know when this dancer came to Australia in 1938, at the age of 36.

Wesley Lim: Yes.

Audience member 2: Whether they had dance or in a conversation, forget Australia, what was happening here, whether she had any premonition of what was going to engulf Europe from 1939 onwards?

Wesley Lim: I think she did, yeah.

Audience member 2: But the point I want to make is because this brings us to the contemporary situation at ANU, that we are not having any discussion on what is happening in the contemporary world next door to us. You might like to comment on the second part.

Wesley Lim: Yeah, no, that totally, that totally makes sense. And that's also kind of one of the things I liked about this was that it was, it was a dance that was always kind of in, a dance practise that was always kind of steeped in realising what was going on socially and politically. And I always take my hat off to dancers that can, and choreographers that can still do that in a very artistic fashion, but have it still, also still read politically. And I think that's one of the interesting things that she did 'cause one of, the dances that happened at the beginning were more kind of, more experimentations on and thoughts about movement. And then later on, moved after '38 and she moved to Australia, then they became, they become more like dance dramas. And I don't have as much, I have records of basically how people have talked about these dances. I have not seen these, so it's difficult for me to kind of make that call. But I think there ended up being more of a political bent or at least being socially aware, and which is in itself is also political. Yeah, yeah. That reflects basically on our time as well when we think about a choreography that's happening in our current moment, yes.

Audience member 3: I may have missed something, but did she work with men as well as women?

Wesley Lim: She did, yeah. And it came a little bit later and that's one of the interesting things that came up in some of the things I was reading. I don't know the particular number. I think they were still in the minority, for sure. But then later on, they came in the company and part of the practises. And I think one of the really interesting things I noticed was when, and this is kind of on the side note, when I looked at the images that came up in the programs, 'cause the programs are really influential and she would always have the thing that said modern dance. And she always had to kind of describe what it is, 'cause I think even for Europeans it was still, if you didn't know what it was and what it was trying to do and its kind of cultural aims, then you always had to kind of prep people what that was. And for Australians, probably even more so. And so they would have, and it's very typical, like they would have the image, you know, a headshot of the dancer and then a bit of a bio. And then for the earlier ones, you would see them extremely hyper-feminized in their Viennese waltzes dresses, slightly, I would even say kind of objectified a little bit and create this really beautiful image. And I was, and I kept saying, "Wow, this is just really, really feminine dance and this is very kind of like '40s, '50s sense." And maybe, I guess at some point later on, became more open to having male dancers that it became maybe something changed within that. I'm actually not sure, but I do know that there were some male dancers later on. Yes, for sure, yeah.

Staff member: We have an online question. How do you think her dance shaped Australian dance traditions? What is her legacy here today or, and abroad?

Wesley Lim: Sure, no, absolutely, fabulous question. And I knew that would come and I'm actually very underprepared for that because I just feel like there is so much knowledge that everyone else has. And I'm still coming as an American and as a foreigner looking in on this, which is also interesting for the kind of theoretical standpoint and history that I come from myself. But I also need to figure that out as well. And I think it's, and it should be quite huge. And I just chatted with the gentleman at the front who actually has danced in some of Bodenwieser's choreography and has relayed to me that this is quite enormous and quite, quite influential. So, and I've had even before this chat, this talk, I've had former dancers, relatives of dancers or people that knew other dancers that danced in the company to write to me to say that they were coming, which was touching. And it made me feel like I was part of something a lot bigger than what it was and something that I'm working on. And to try to encapsulate the enormity of an entire archive and an entire body's bodily knowledges is actually quite difficult. So yes, it was huge. I think would be that, but to, yes to get to more specifics, I would have to do more research for sure. Thank you, yeah.

Kathryn Favelle: Great, thank you so much for your questions. And Wesley, I have a feeling that your relationship with Gertrud Bodenwieser may be continuing for a long, long time yet.

Wesley Lim: Oh, absolutely so, yes.

Kathryn Favelle: There's much for you to learn. Thank you so much...

Wesley Lim: Thank you.

Kathryn Favelle: ...for tonight's presentation, sharing your research with us.

Wesley Lim: Thank you everyone for coming, this is wonderful.

Kathryn Favelle: Of course, as we wind up this evening, it would be remiss of me if I didn't plug our next Fellowship Lecture. We are going to move to a different part of the world entirely. I hope you can join us at 12:30 on Thursday the 15th of February, where Dr. Mei-Fen Kuo will be talking to us about the Chinese diaspora in Cold War Australia, so something a little bit different. But thank you all for coming tonight. Thank you, Wesley, for sharing your research and for opening up Gertrud Bodenwieser's photographic representations for us so beautifully. Hope we can see you all again sometime soon. Thank you for joining us at the National Library.

Seeing the full picture

In addition to the Papers of Gertrud Bodenwieser, Wesley found a wealth of information in the papers of adjacent figures, archivists and dancers in Bodenwieser’s company.

‘One dancer named Innes Williams had around 6 personalised scrapbooks that directly reflect the art of collecting materials and memorabilia (newspapers clippings, photographs) and displaying them. She had collected a number of folded newspaper images from a publication called Pix, which featured some of the Bodenwieser dancers, particularly when they left the company to begin their own dance projects.’

Wesley was also able to learn from a number of dancers, former dancers, and relatives of those associated with Bodenwieser who contacted him during his research.

‘Their stories and presence help add to my knowledge and Bodenwieser’s living archive through their narratives.’

Onto the next chapter

Though his fellowship has now come to an end, there is much more Wesley plans to explore in the collection. With the intention of turning his research into a book, he’s working on identifying photographers and specific photographs used in programs, posters, magazines and newspapers to be included.

The Fellowship experience

Reflecting on his time at the Library, it seems the people he met and worked with were an important highlight. This includes both the ‘welcoming and knowledgeable’ staff that helped him throughout this research journey, and the other fellows he worked alongside.

'I really enjoyed learning about their projects and sharing our experiences of viewing and researching archival material at the NLA.’

Learn more about our fellowships and scholarships program.