Due to scheduled maintenance, the National Library’s online services will be unavailable between 8pm on Saturday 7 December and 11am on Sunday 8 December (AEDT). Find out more.

The idea for Australian Dreams: Picturing our Built World, an exhibition of images of the built environment, came from an unlikely place—the work of wilderness photographer Peter Dombrovskis. Three years ago, the National Library of Australia did an exhibition—Peter Dombrovskis: Journeys Into The Wild—based on its Dombrovskis archive of 3,000 transparencies. Of the 80 works on display, only one showed any signs of human intervention—a faint hint of the city of Hobart in the distance from the top of Mount Wellington. In the rest of the photos there wasn’t a house, shop, school, church or bridge in sight. They were beautiful, reflective images that highlighted the importance of the natural environment and why it was worth saving. It celebrated the parts of Australia’s environment that remained ‘untouched’.

As I looked at Dombrovskis’ images of forests, mountains and lakes, I began to think about the ‘other’ outdoors, the ‘built’ outdoors. What would an exhibition about the built environment, about architecture, look like? How have our artists engaged with cityscapes, the main streets of country towns, homesteads, churches, shearing sheds, post offices, skyscrapers and the humble suburban home.

Charles Bayliss, Pitt Street from Hunter Street, Sydney, New South Wales, ca. 1880, nla.cat-vn4269708.

After searching through the National Library’s Collections I found plenty of amazing images of the built environment by Australia’s greatest painters, printmakers and photographers. More than enough to make what I thought could be a beautiful and thought provoking exhibition. Drawing exclusively from the collections of the National Library, Australian Dreams: Picturing our Built World features paintings, drawings, prints, and photographs by Augustus Earle, Conrad Martens, S. T. Gill, Eugene von Guérard, Lionel Lindsay, Harold Cazneaux, Olive Cotton, Mark Strizic, David Moore, Max Dupain, Jeff Carter, Ruth Maddison, Wolfgang Sievers and John Gollings.

Harold Cazneaux, Going Home, North Sydney, New South Wales, 1910, nla.cat-vn6808586.

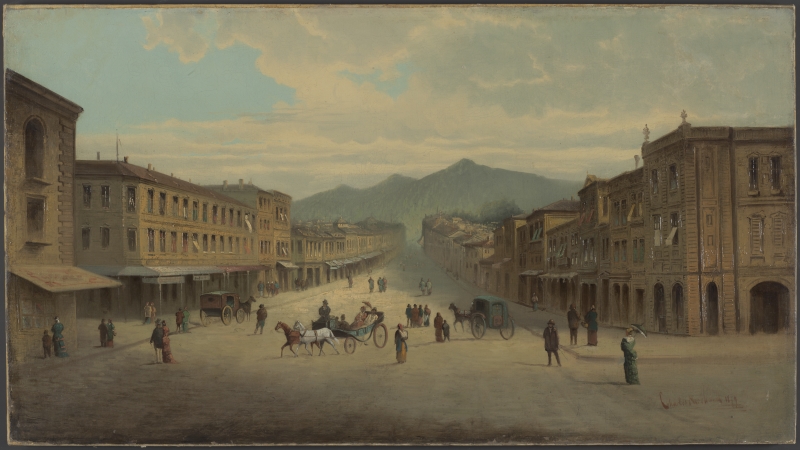

Australian Dreams begins with images from the colonial era. With the arrival of the First Fleet in 1788, European artists began recording the development of the Australian colonies. Throughout the nineteenth century, they produced paintings, prints and photographs of streetscapes and major public buildings in the new cities and towns. They also documented Indigenous Australian dwellings and farm buildings on frontier properties. Often commissioned by governments and landholders, these images were seen as proof of the success of European settlement. The dispossession of Indigenous people and the changes made to the natural environment were rarely addressed in these celebratory images.

The next section of the exhibition looks at the images produced in the first decades of the twentieth century, when many artists produced sentimental pictures of Australia’s colonial past. Artists such as Lionel Lindsay, Harold Cazneaux and Hardy Wilson created romantic images of old Sydney, the bush and grand colonial buildings. It was a built environment that they saw as important to Australian identity but under threat. Two trends that influenced these images were the revival of etching in printmaking and a more impressionistic and expressive approach to photography.

Charles Blanchard, Liverpool Street, Hobart Town [picture] / Charles Blanchard, 1879, nla.cat-vn379039.

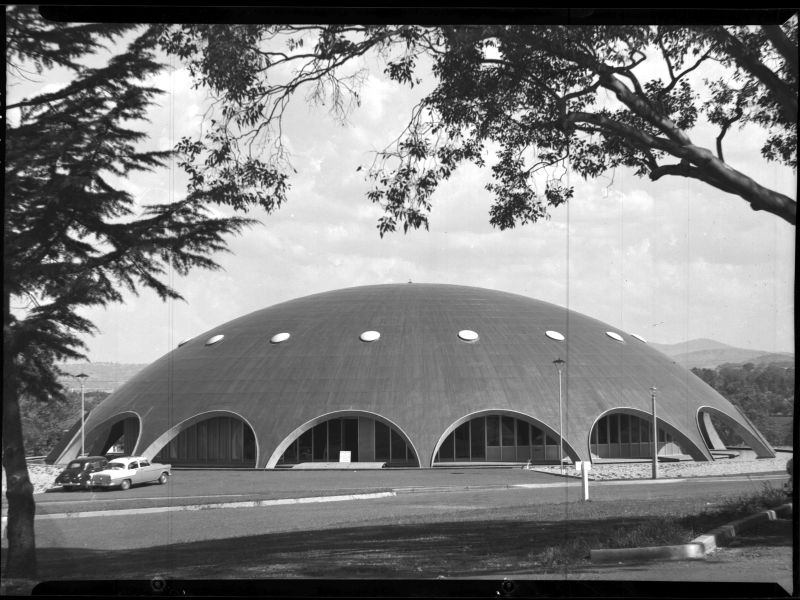

After a series of images in which artists and photographers look back with nostalgia, the next section of the exhibition is about looking forward. As the twentieth century progressed, modernism began to dominate Australian photography, architecture, design and literature. A collection of ideas rejecting the styles of the past, modernism was a response to the massive social, political and technological changes happening in the Western world. The common elements of modernist photography were compositions that embraced abstraction; severe contrast between shadow and light; sharply delineated forms; and an energetic interaction of vertical, horizontal and diagonal lines. This perfectly matched the clean lines of Australia’s post-war architecture, but was also used to capture old buildings and familiar streetscapes in a new way.

In the latter part of the twentieth century, artists and photographers continued to be inspired by the beauty and formal qualities of architecturally significant buildings.

Frank Hurley, [Australian Academy of Science building, Canberra] [picture] / [Frank Hurley], 1959, nla.cat-vn81358.

The images in the final rooms demonstrate how they also found something compelling in the everyday, capturing buildings where ordinary lives played out, in various states of use, disuse, demolition and destruction. With the rise of the heritage movement, artists created images that visually communicated why buildings are worth seeing and saving: not just because they are architecturally significant, but because they tell us something about ourselves and the rich variety of Australian life.

The artists in Australian Dreams have documented, interpreted and celebrated a variety of buildings, from the inner-city terrace and the humble bush cottage to the Sydney Opera House and Melbourne’s Flinders Street Station. Sometimes beautiful, sometimes ordinary, these buildings are the backdrops to our lives. They reflect our sense of identity, our hopes and dreams, rendered in bricks and mortar. I hope you have the opportunity to visit the exhibition and enjoy this journey through our built environment, with material drawn exclusively from the collections of the National Library of Australia.

See more of the works from Australian Dreams: Picturing our Built World online.