This year’s ANZAC Day will be very different from previous ones with social distancing meaning traditional dawn services and marches won’t be able to proceed in their usual way.

Fairfax Corporation, 1933, Child playing with the medals of a returned soldier at the ANZAC Day service at Petersham [?], New South Wales, 25 April 1933, nla.cat-vn6266577

For those who wish to connect with the sacrifice and significance of ANZAC Day, there is a rich variety of collection material held by the Library that can be accessed online at home, allowing for some quiet reflection on the ANZAC legacy.

Material from the Oral History and Folklore collection includes memories and first hand perspectives of veterans from the First World War - remembering events of more than 100 years ago - as well as men and women who served in subsequent conflicts.

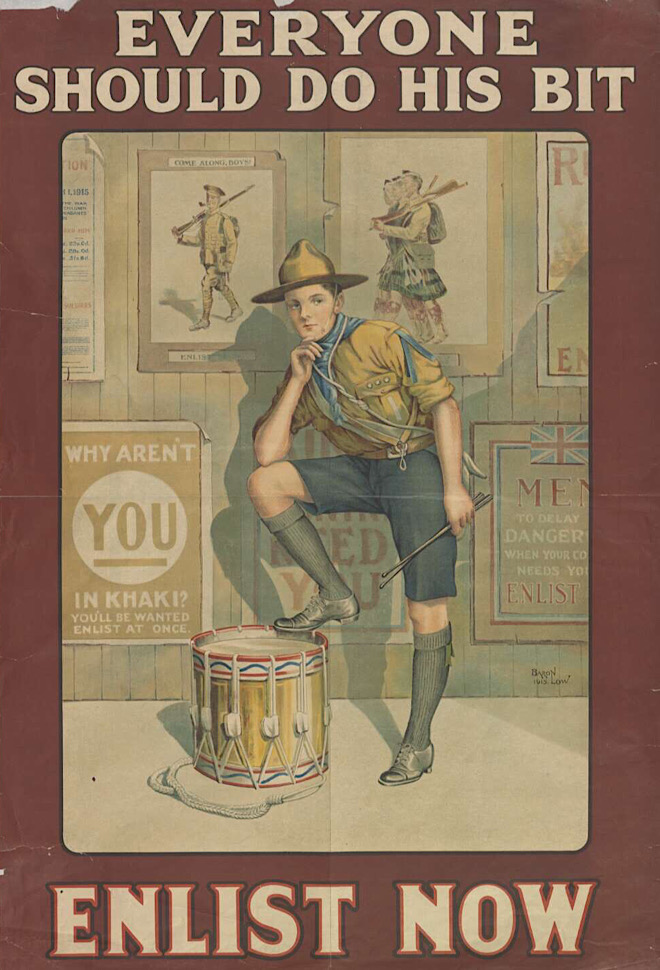

Alec Campbell, who was known as Australia’s last ANZAC as he was the last surviving participant of Gallipoli, tells his remarkable story. He joined the Australian Army at just sixteen years of age from Tasmania and told the recruiting office he was eighteen. About enlisting he says: “I was sixteen when I left school and enlisted… You don’t look for reasons why I did this, you just did it…. Most young fellas were going, umm, and… See I was only sixteen - I was not very mature to make decisions of any sort!”

He says he was not fully aware of just how dangerous service overseas would be. “We must’ve heard something about it, I suppose. But you know, at sixteen it doesn’t seem to matter much… A little bit older you’d think more seriously about it!” Once at Gallipoli though,

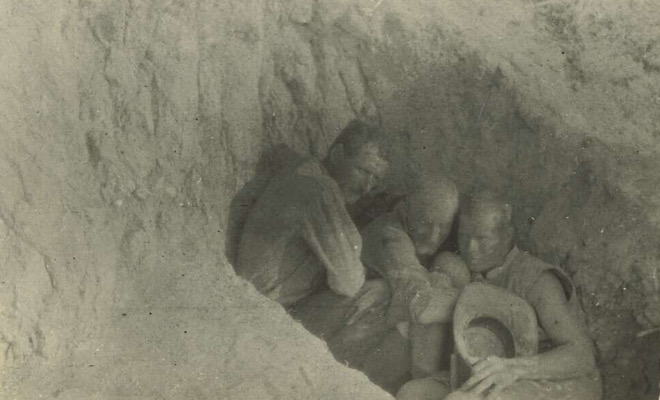

“You were aware that you could get killed any time, but you couldn’t do anything about it.”

Listen to Alec Campbell's interview

Low, Baron. & Great Britain. Parliamentary Recruiting Committee, 1915, Everyone should do his bit: enlist now [poster], nla.cat-vn6777711

Harold Clive Newman was hit with a ricochet at Gallipoli, though he explains that was not considered a reason to stop serving. “And in the early days in Gallipoli- I don't know if you know this or not- but you were not... a man was not reported as wounded unless he had been hospitalised. Minor wounds were just dismissed until some of them became dangerous and infected and then, then they realised they had to do something about it. But all I had was a bullet in the back of the right shoulder and that was extracted with a local anaesthetic, patched up and I never left the line. I stayed there.”

Listen to Harold Clive Newman's interview

The impact of serving in the First World War left many men with physical wounds or what would now be recognized as post-traumatic stress. In the aftermath of the First World War though, there was no recognition of the heavy toll that wartime service could take. Nancy Coe, whose father was a World War I veteran, remembers that her father used to wake up with nightmares and disturbed sleep because of his experience, which he was reluctant to talk about. Nancy remembers, “When I was fifteen dad took me out to ANZAC day with him. And I stayed for the afternoon with the old boys and shared their meals and the rest of it. And between then and the end of June that year, dad and I had quite a number of talks and I tried to draw him out.” Nancy’s father was fortunate as she feels that she was able to help him. After he did eventually speak to her about his war experiences, “he never had a disturbed night or cried out again.”

Listen to Nancy Coe's interview

Campbell, J. P., 1915, Sheltering from bursting shells, [showing three Anzac soldiers huddled together sheltering in a shallow trench, June? 1915], nla.cat-vn1504935

The sacrifice of those who served in the First and Second World War was recognized with particularly moving words from Australian Prime Minister John Gorton at an ANZAC Day Service in Ballarat, Victoria in 1968. He said:

“Twice in my generation, young Australians have left their homes and their families, their farms, their professions, and have marched off because they felt there was a need for them to do this - not for themselves, not only for the nation to which they belonged, but for the world”.

Listen to John Gorton's speech

While First Nations Australians have long served Australia with courage and distinction, this service has only recently been recognised. The Indigenous ex-service men and women oral history project features the voices of First Nations service men and women who served their country, even when they were treated as second-class citizens in their own country.

Listen to the interviews with Indigenous ex-service men and women

War and conflict have cast a long shadow over Australia, particularly throughout the twentieth century. Listening to the recollections of those who served their country provide a unique insight into the sacrifice and courage of such individuals.