From the first ‘inky wayfarers’ and ‘penny liners’ to the political editors who lead the Australian press gallery today, women have always been a crucial part of journalism. ‘Anonymous’ may have been a woman, but there were many others watching history unfold under a by-line, analysing and explaining it through their own lens – all while hearing how they couldn’t possibly understand the significance of the events they were both witnessing and living. But it is precisely women’s experiences, as distinct from men’s, our views and, yes, emotions that not only set us apart, but help to tell the stories history, and men, have missed.

Patricia Clarke began her journalism career in 1951, not long after the final story told in her latest book, Bold Types: How Australia’s First Women Journalists Blazed a Trail, published by the National Library of Australia. Seven decades later, Pat is still telling stories, still shining a light into parts of history the patriarchy left dark, giving those women back their voices. Pat has stood sentry over an unfolding history we don’t like to acknowledge in the media, given the industry’s penchant for considering itself an overall progressive force. She was part of a workforce that pushed not only for equality, but respect, a push that eventually snowballed into the end of the ‘women’s pages’ and saw women’s by-lines take their rightful place alongside their male colleagues’. From police stations to Parliament House, Pat has both recorded history and helped make it.

Bold Types is just part of Patricia Clarke’s professional legacy, which began when she first stepped into a newsroom 71 years ago. The stories she tells here are timeless, made richer by her own experiences and understanding of both the differences and commonalities. Having lived and contributed to the changes, Pat is perhaps one of the only voices in Australian journalism who can tell you these stories – as well as let you know just how much there still is to change.

There have been gains. And wins. And defying the odds. The women in this book, through their fight and determination, paved the way for the women editors, correspondents and media leaders we know now. There is no Katharine Murphy, Laura Tingle, Patricia Karvelas, Fran Kelly, Leigh Sales, Samantha Maiden or Karen Middleton without Stella Allan, who, despite being refused a seat in the (then all-male) New Zealand parliamentary press gallery, became the first woman parliamentary reporter in either Australia or New Zealand – from the special cubicle where she was segregated.

There is no Avani Dias or Isabella Higgins or Zoe Daniel (in her incarnation as a foreign correspondent) without Janet Mitchell, who watched as Japanese troops marched into the Chinese province of Manzhou (Manchuria), capturing the moment many now see as a precursor to the Second World War in letters to her family, which she later turned into a series of broadcasts for the ABC upon her return to Australia. Maxine McKew, Pru Goward and now Daniel are part of a long line of women journalists who saw an opportunity to better create change by joining politics, instead of just reporting on it, which owes a debt of gratitude to Alice Henry, a woman who resigned her rather constricting position in Australian journalism to fight for women’s suffrage, not just in Australia, but in the United States.

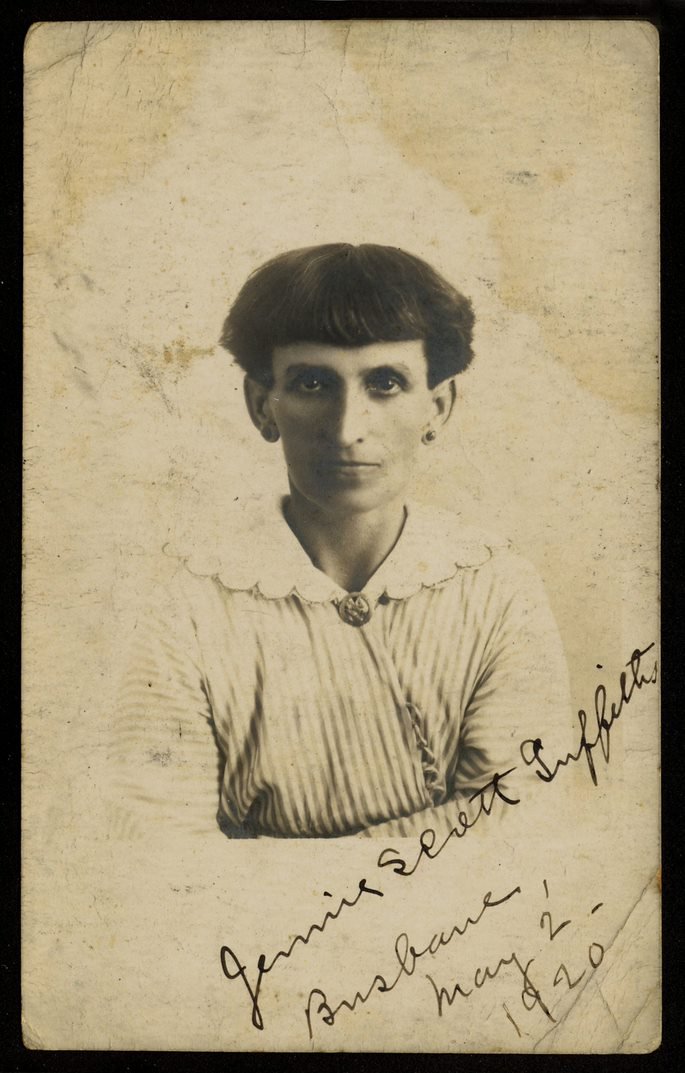

There is no Lenore Taylor, Michelle Grattan, Gay Alcorn, Lisa Wilkinson or Lisa Davies without Jennie Scott Griffiths, the first female editor of a weekly women’s paper. Scott Griffiths had already worked as the ‘unacknowledged, unpaid’ editor of the Fiji Times when it had been under her husband’s stewardship. In 1915, she was able to put her name to her editorship of the Woman’s Weekly – two years after she had been given the job. Pat will tell you the rest of that story.

But there is still so far to go. When it comes to race, religion, gender and disability, there always is – particularly when there is any intersectionality. For all its gains, there is still a stunning lack of diversity in media and, as women have shown, a diversity of voices and experiences makes our national story richer. It can be easy to forget how far we have come when looking at the state of the profession for women today. But the pioneering battle of the women Pat profiles, these bold types, is the reason we are here to carry it on.

This is an edited and abridged version of Amy Remeikis’ introduction to Bold Types by Dr Patricia Clarke.

About the Book

Bold Types tells the story of women journalists in Australia covering the period from 1860 to the end of World War II.

Tracing the journey of more than 13 independent, adventurous women who ventured far and wide and fought for relevance and gender equality, together these stories illustrate the gains and setbacks of women journalists over nearly a century. In each successive story, their tenacious determination and courage shines through.

Author Patricia Clarke was a trailblazer herself, as the only woman on the Melbourne staff at the Australian News and Information Bureau in the early 1950s.

Bold Types: How Australia’s First Women Journalists Blazed a Trail is launching at the National Library of Australia on Tuesday 29 November 2022. This event is free but bookings are essential